Desire For Integration

By Angel Perez

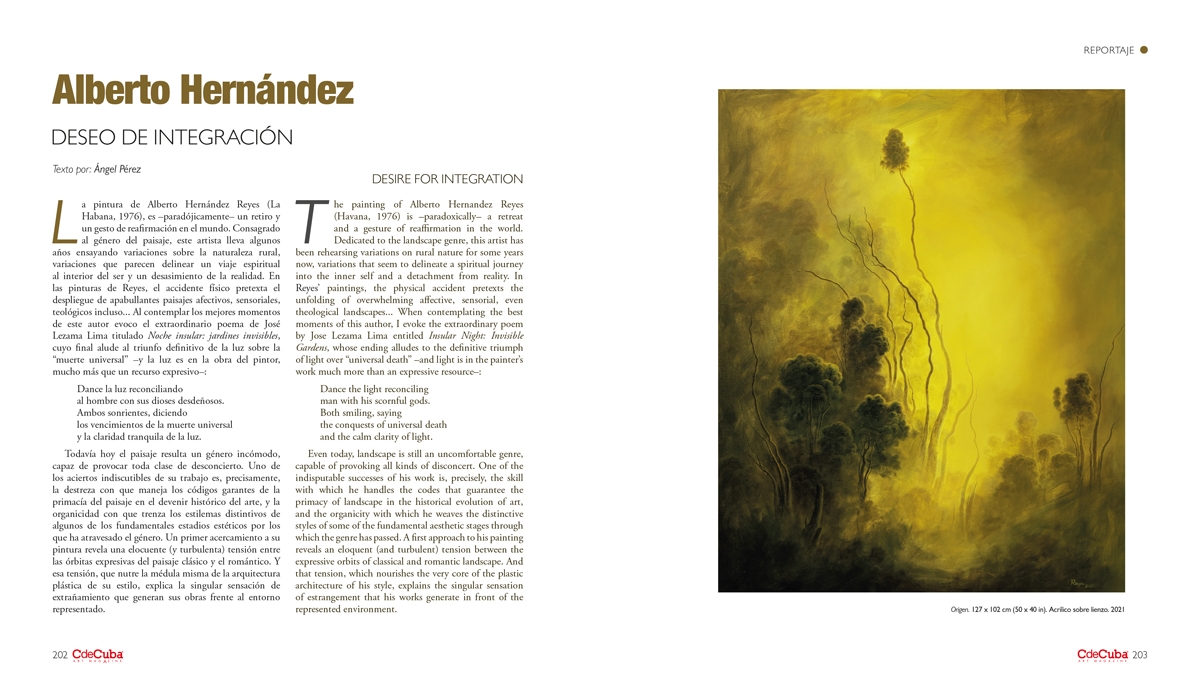

The painting of Alberto Hernandez Reyes (Havana, 1976) is –paradoxically– a retreat and a gesture of reaffirmation in the world. Dedicated to the landscape genre, this artist has been rehearsing variations on rural nature for some years now, variations that seem to delineate a spiritual journey into the inner self and a detachment from reality. In Reyes’ paintings, the physical accident pretexts the unfolding of overwhelming affective, sensorial, even theological landscapes… When contemplating the best moments of this author, I evoke the extraordinary poem by José Lezama Lima entitled Insular Night: Invisible Gardens, whose ending alludes to the definitive triumph of light over “universal death” -and light is in the painter’s work much more than an expressive resource-:

Dance the light reconciling

man with his scornful gods.

Both smiling, saying

the conquests of universal death

and the calm clarity of light.

Even today, landscape is still an uncomfortable genre, capable of provoking all kinds of disconcert. One of the indisputable successes of his work is, precisely, the skill with which he handles the codes that guarantee the primacy of landscape in the historical evolution of art, and the organicity with which he weaves the distinctive styles of some of the fundamental aesthetic stages through which the genre has passed. A first approach to his painting reveals an eloquent (and turbulent) tension between the expressive orbits of classical and romantic landscape. And that tension, which nourishes the very core of the plastic architecture of his style, explains the singular sensation of estrangement that his works generate in front of the represented environment.

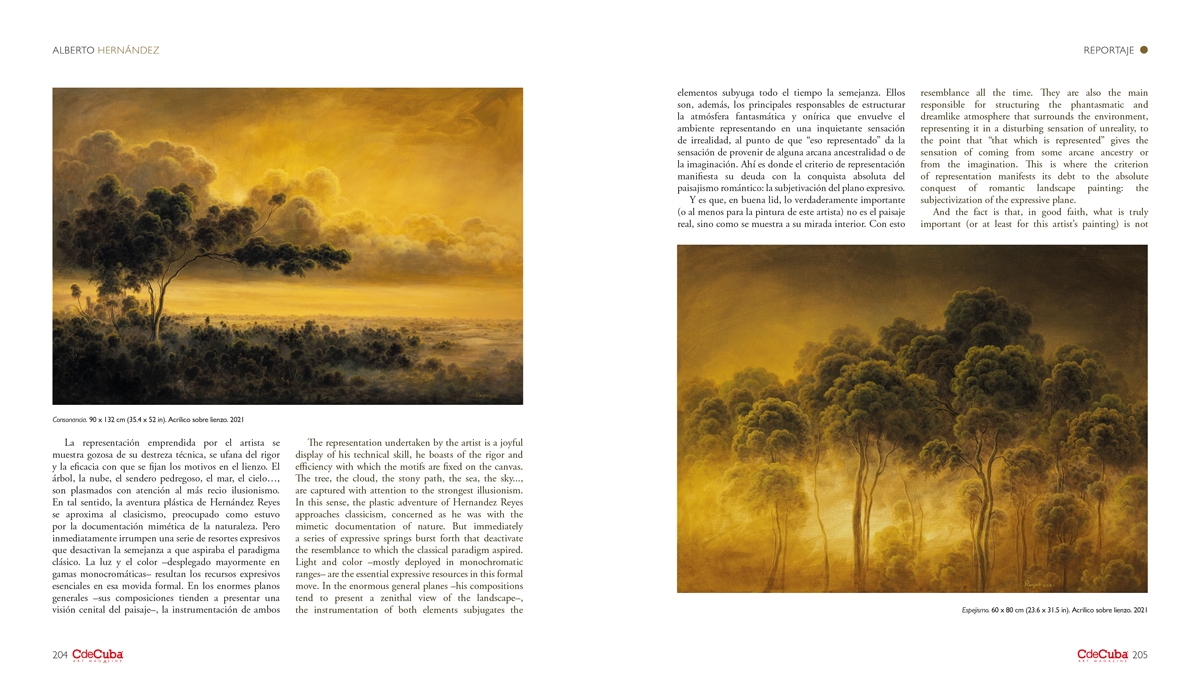

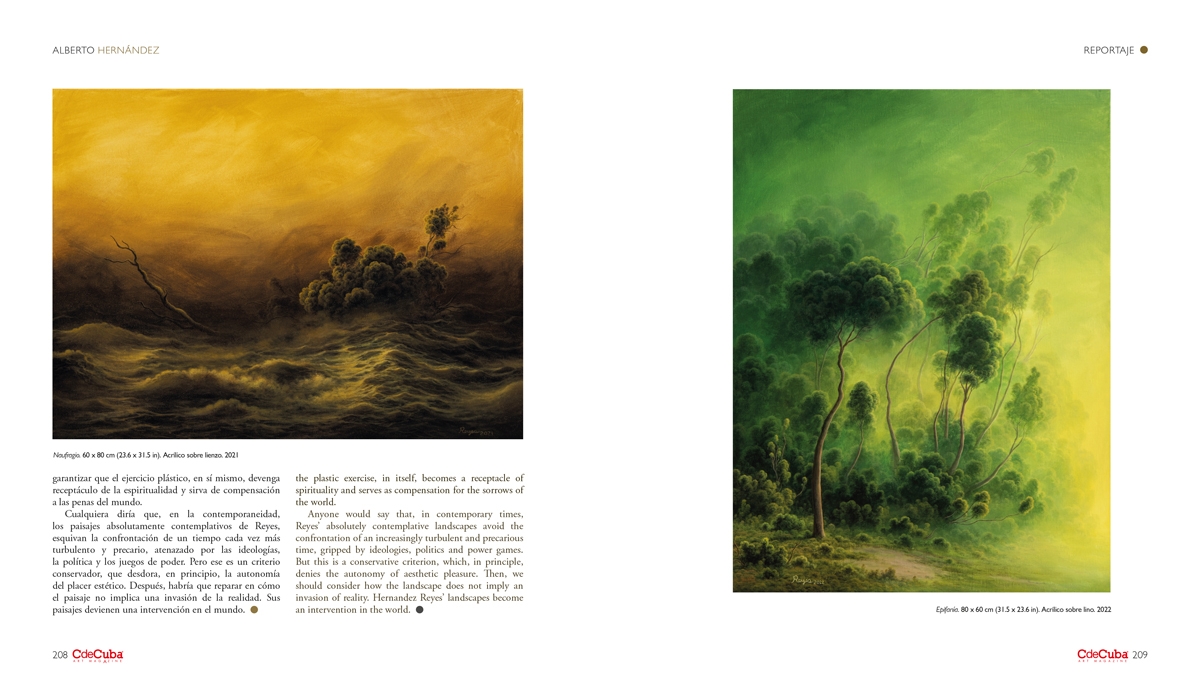

The representation undertaken by the artist is a joyful display of his technical skill, he boasts of the rigor and efficiency with which the motifs are fixed on the canvas. The tree, the cloud, the stony path, the sea, the sky…, are captured with attention to the strongest illusionism. In this sense, the plastic adventure of Hernandez Reyes approaches classicism, concerned as he was with the mimetic documentation of nature. But immediately a series of expressive springs burst forth that deactivate the resemblance to which the classical paradigm aspired. Light and color –mostly deployed in monochromatic ranges– are the essential expressive resources in this formal move. In the enormous general planes -his compositions tend to present a zenithal view of the landscape-, the instrumentation of both elements subjugates the resemblance all the time. They are also the main responsible for structuring the phantasmatic and dreamlike atmosphere that surrounds the environment representing it in a disturbing sensation of unreality, to the point that “that which is represented” gives the sensation of coming from some arcane ancestry or from the imagination. This is where the criterion of representation manifests its debt to the absolute conquest of romantic landscape painting: the subjectivization of the expressive plane.

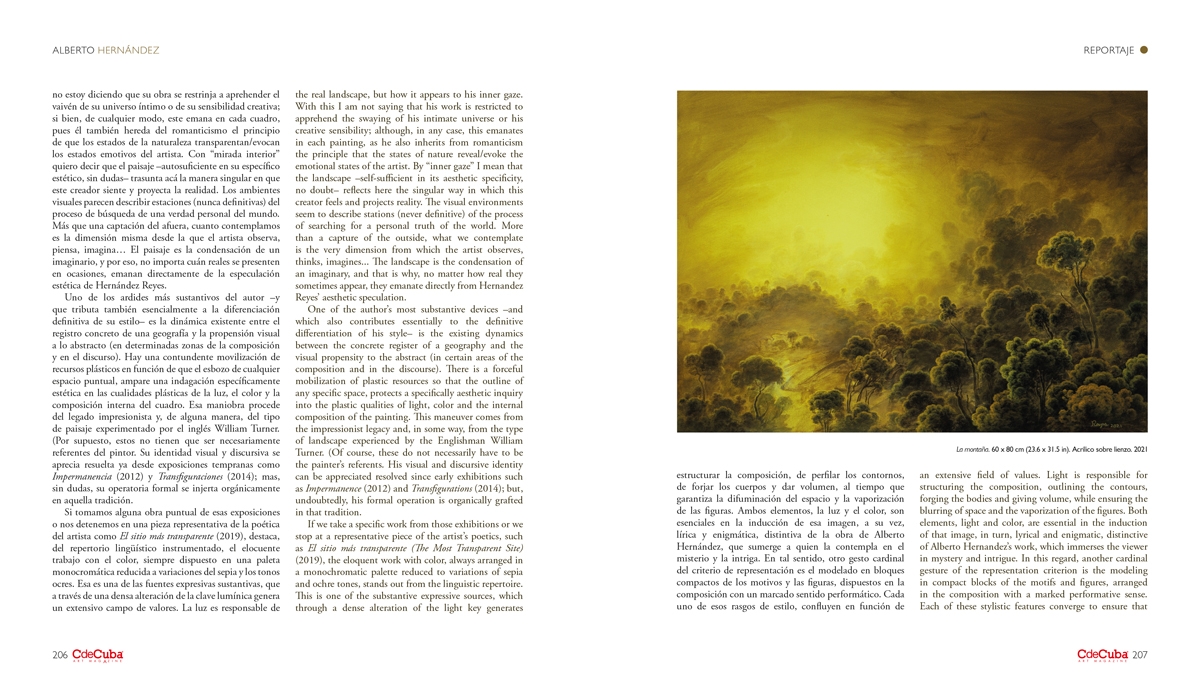

And the fact is that, in good faith, what is truly important (or at least for this artist’s painting) is not the real landscape, but how it appears to his inner gaze. With this I am not saying that his work is restricted to apprehend the swaying of his intimate universe or his creative sensibility; although, in any case, this emanates in each painting, as he also inherits from romanticism the principle that the states of nature reveal/evoke the emotional states of the artist. By “inner gaze” I mean that the landscape –self-sufficient in its aesthetic specificity, no doubt– reflects here the singular way in which this creator feels and projects reality. The visual environments seem to describe stations (never definitive) of the process of searching for a personal truth of the world. More than a capture of the outside, what we contemplate is the very dimension from which the artist observes, thinks, imagines… The landscape is the condensation of an imaginary, and that is why, no matter how real they sometimes appear, they emanate directly from Hernandez Reyes’ aesthetic speculation.

One of the author’s most substantive devices –and which also contributes essentially to the definitive differentiation of his style– is the existing dynamics between the concrete register of a geography and the visual propensity to the abstract (in certain areas of the composition and in the discourse). There is a forceful mobilization of plastic resources so that the outline of any specific space, protects a specifically aesthetic inquiry into the plastic qualities of light, color and the internal composition of the painting. This maneuver comes from the impressionist legacy and, in some way, from the type of landscape experienced by the Englishman William Turner. (Of course, these do not necessarily have to be the painter’s referents. His visual and discursive identity can be appreciated resolved since early exhibitions such as Impermanence (2012) and Transfigurations (2014); but, undoubtedly, his formal operation is organically grafted in that tradition.

If we take a specific work from those exhibitions or we stop at a representative piece of the artist’s poetics, such as El sitio más transparente (The Most Transparent Site) (2019), the eloquent work with color, always arranged in a monochromatic palette reduced to variations of sepia and ochre tones, stands out from the linguistic repertoire. This is one of the substantive expressive sources, which through a dense alteration of the light key generates an extensive field of values. Light is responsible for structuring the composition, outlining the contours, forging the bodies and giving volume, while ensuring the blurring of space and the vaporization of the figures. Both elements, light and color, are essential in the induction of that image, in turn, lyrical and enigmatic, distinctive of Alberto Hernandez’s work, which immerses the viewer in mystery and intrigue. In this regard, another cardinal gesture of the representation criterion is the modeling in compact blocks of the motifs and figures, arranged in the composition with a marked performative sense. Each of these stylistic features converge to ensure that the plastic exercise, in itself, becomes a receptacle of spirituality and serves as compensation for the sorrows of the world.

Anyone would say that, in contemporary times, Reyes’ absolutely contemplative landscapes avoid the confrontation of an increasingly turbulent and precarious time, gripped by ideologies, politics and power games. But this is a conservative criterion, which, in principle, denies the autonomy of aesthetic pleasure. Then, we should consider how the landscape does not imply an invasion of reality. Hernandez Reyes’ landscapes become an intervention in the world.