Puppet Master in the Altarpiece of History

Alberto Lorente and His Endless Strategy of Building Meanings

By Ernesto Santana

“I would like the visitors to have, more or less, all the information they require to grant meaning to what they are faced with,” Hans Haacke once said. The visitors are more faced to the work than the work is to them, because the question is not to tour an art exhibition but to find your own inner self.

The use of “all the information the visitors require” is essential “to grant meaning” to that aesthetic experience. Lorente turns the delivery and concealment of information into a strategic movement of his relevant projects. Dizzying questions arise in the face of a convincing hyper-realistic piece and the scandalous absence of an explicit reason for its presence.

From distant projects such as El ojo sobre la ciudad (The Eye on the City) or Proyecto Vuelo (Flight Project) with its unrepeatable kites across Havana’s skies; and from his first tiny vehicles to transport us to a superimposed city, Lorente has always pretended to dislocate the meanings and orbit them to decipher their alignment, explore the thoughtlessness that draws them and update an ancestral battle by playing with signs in an ancient stadium of our city.

Because “good is what was or will be, but never is”, reminds Emil Cioran when talking to us about the “fateful demiurge” and the “insubstantiality” of good as “great unrealistic force”, as “principle that has aborted from the beginning” and “parasite of memory or premonition.” Finally, the creator god turns the devil into “an angel degraded to a lowly task, history.”

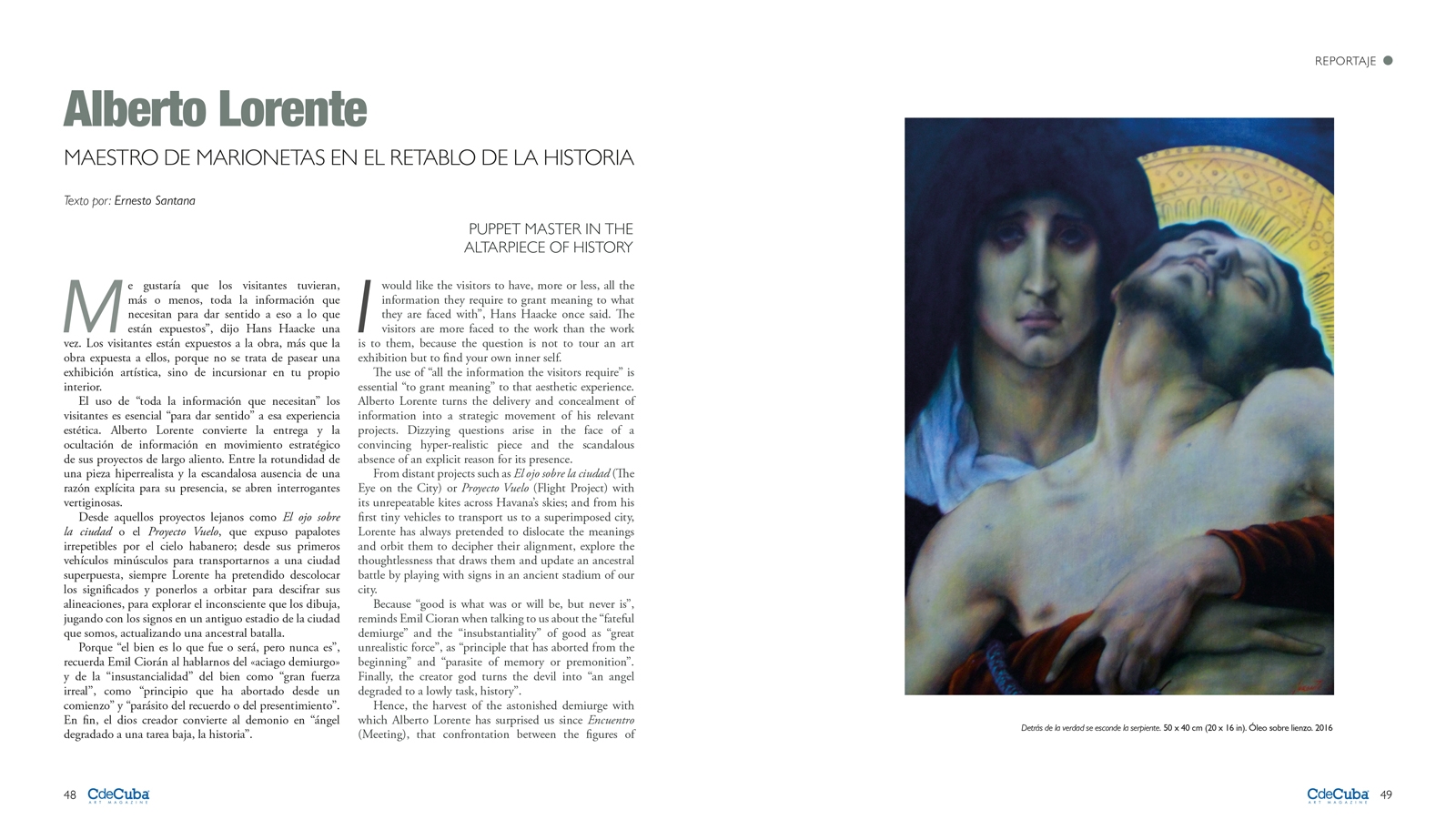

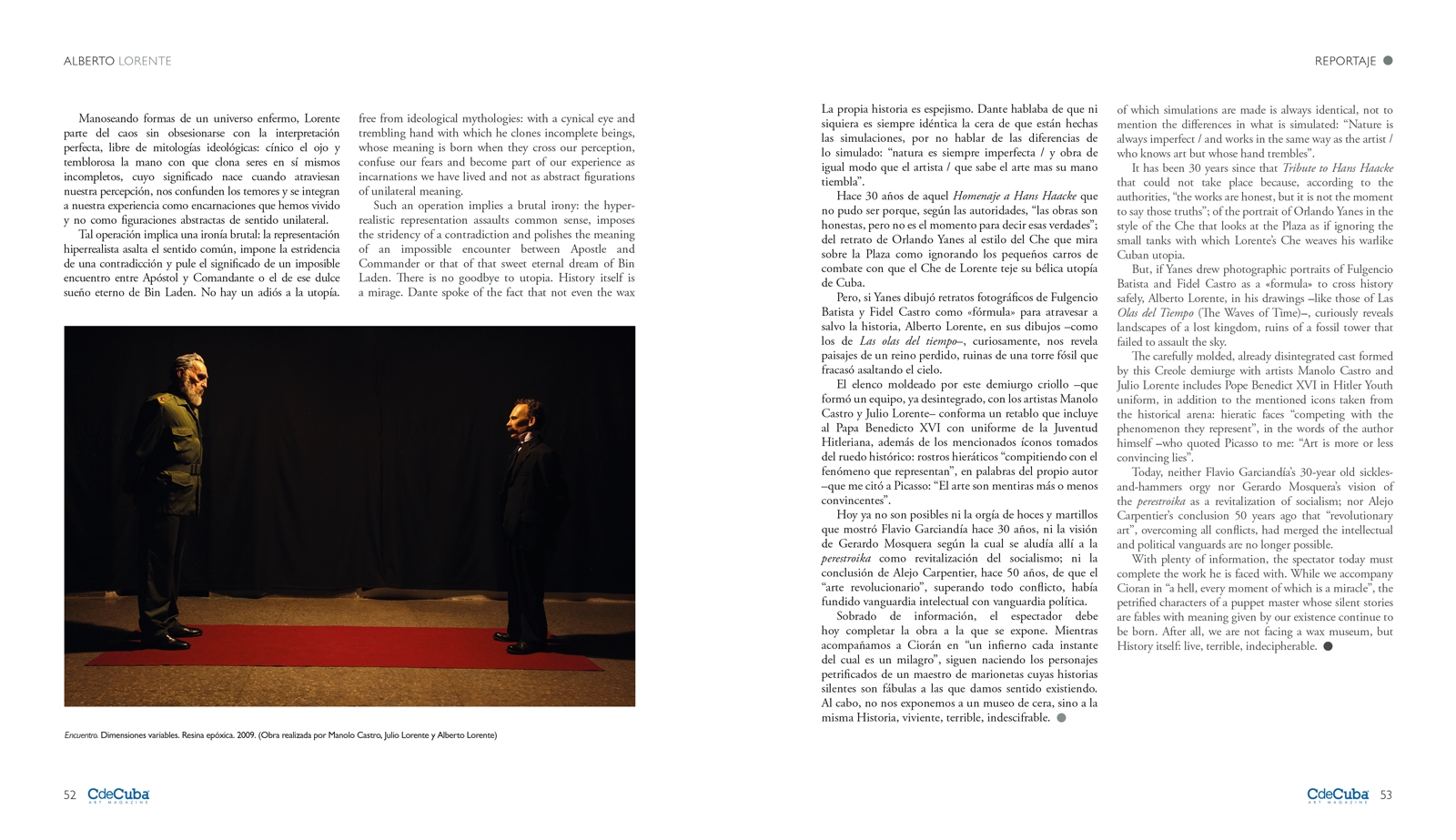

Hence, the harvest of the astonished demiurge with which Alberto Lorente has surprised us since Encuentro (Meeting), that confrontation between the wax figures of Fidel Castro, somewhat bent over and in military uniform, and the sober and civil José Martí: that premonition about the location in symbolic proximity that today resounds in the silence of Santa Ifigenia cemetery in Santiago de Cuba.

The story, with its screaming soap opera episodes, in our case is not reduced to the nightmare that Joyce wanted to wake up from, but can become a carnival parade with big colorful cardboard heads. History as hallucination or as a personal story. Whatever. In the world of the demiurge -“master”, “supreme craftsman” – salvation does not depend on beliefs or divine mercy, but on revelation, a private matter.

Handling forms of a sick universe, Lorente starts from chaos without being obsessed with a perfect interpretation, free from ideological mythologies: with a cynical eye and trembling hand with which he clones incomplete beings, whose meaning is born when they cross our perception, confuse our fears and become part of our experience as incarnations we have lived and not as abstract figurations of unilateral meaning.

Such an operation implies a brutal irony: the hyper-realistic representation assaults common sense, imposes the stridency of a contradiction and polishes the meaning of an impossible encounter between Apostle and Commander or that of that sweet eternal dream of Osama bin Laden. There is no goodbye to utopia. History itself is a mirage. Dante spoke of the fact that not even the wax of which simulations are made is always identical, not to mention the differences in what is simulated: “Nature is always imperfect / and works in the same way as the artist / who knows art but whose hand trembles.”

It has been 30 years since that Tribute to Hans Haacke that could not take place because, according to the authorities, “the works are honest, but it is not the moment to say those truths”; of the portrait of Orlando Yanes in the style of the Che that looks at the Plaza as if ignoring the small tanks with which Lorente’s Che weaves his warlike Cuban utopia.

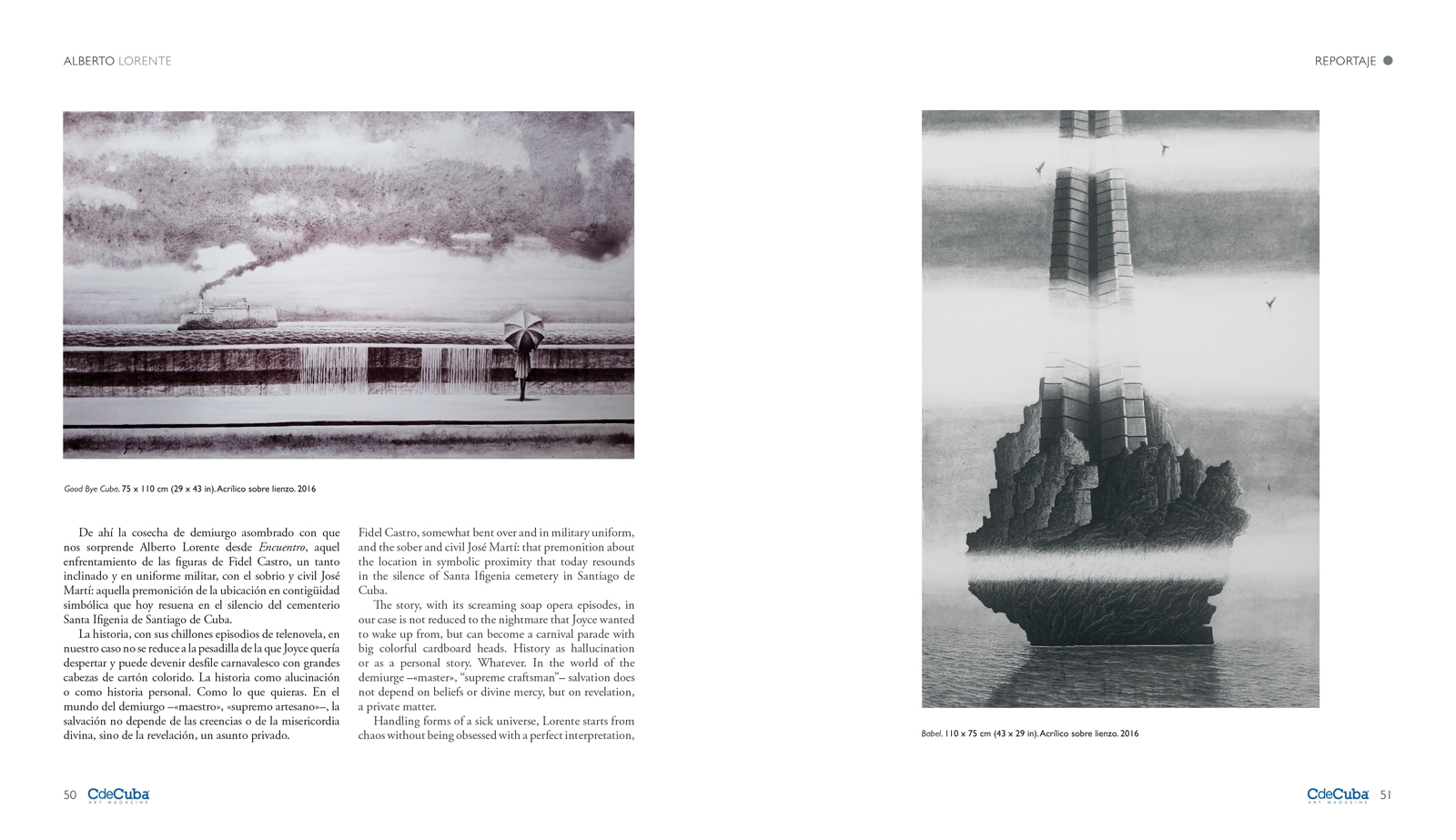

But, if Yanes drew photographic portraits of Fulgencio Batista and Fidel Castro as a “formula” to cross history safely, Alberto Lorente, in his drawings – like those of Las Olas del Tiempo (The Waves of Time)-, curiously reveals landscapes of a lost kingdom, ruins of a fossil tower that failed to assault the sky.

The carefully molded, already disintegrated cast formed by this Creole demiurge with artists Manolo Castro and Julio Lorente includes Pope Benedict XVI in Hitler Youth uniform, in addition to the mentioned icons taken from the historical arena: hieratic faces “competing with the phenomenon they represent”, in the words of the author himself -who quoted Picasso to me: “Art is more or less convincing lies.”

Today, neither Flavio Garciandía’s 30-year old sickles-and-hammers orgy nor Gerardo Mosquera’s vision of the perestroika as a revitalization of socialism; nor Alejo Carpentier’s conclusion 50 years ago that “revolutionary art”, overcoming all conflicts, had merged the intellectual and political vanguards are no longer possible.

With plenty of information, the spectator today must complete the work he is faced with. While we accompany Cioran in “a hell, every moment of which is a miracle”, the petrified characters of a puppet master whose silent stories are fables with meaning given by our existence continue to be born. After all, we are not facing a wax museum, but History itself: live, terrible, indecipherable.