Counter-Blow Nostalgia

By Ricardo Alberto Pérez

The greatest wealth of Franklin Álvarez’s work is linked to his deep capacity to dialogue with numerous symbols and references that illustrate with precision core aspects of the nation’s life in recent decades. Having evaluated his work prior to the present gives me the possibility of witnessing the evolution of the main obsessions that contribute a body of painting and a subjective halo to his work.

We stand before stories or scenes that we know very well because in one way or another they have left their trace in our lives. Hence, bodybuilding, boxing, exodus, the poverty that generates extreme situations, and the boredom caused by our own hopelessness become great protagonists. Most significant is how each one of the works incorporates the mutations produced in these topics by the passing of time and destiny, both individual and collective, as well as the way of exposing the dramas and conflicts inflicted upon the body under the circumstances described in his drawings and paintings.

The characters themselves guarantee a style; a way of saying from any scenario in which they develop; their often anonymous condition is an expressive force capable of granting quality to the images both separately and as a whole. Franklin immerses us in a fragmented or broken narrative that never clearly shows if it speaks of progress or deterioration, but it does leave symptoms that can be interpreted freely by the viewer at all times.

A subject such as boxing, due to its dynamics and ways of ending, has allowed him to transfer that spirit to the exercise of painting (perhaps in Jackson Pollock’s manner) since one of the elements related to this sport is blood, which at the same time offers ample possibilities for performance. The irony becomes cruel in those passages; such is the case of El Guiño (The Wink) (2018), where the athlete’s eye is closed not because he is making a sign but because of the blows he has received. Other works in this line also draw attention: Golpe con sabor a Cuba (Blow with a Taste of Cuba)(2018), and Boxer with Dripping (2018).

In our context, boxing has been closely linked to the official ideology and therefore to the entire utopian machinery installed within the island; the artist takes advantage of this detail to increase the tension and therefore the impact of the pieces. It is significant that Franklin had already approached boxing with the series Punching Bags (2005-2008), where several punching bags with portraits appeared; there is an open metaphor that comments on “the blows” that each of these beings will receive in the course of their lives.

In his current work he acquires a transforming vitalit: the reuse of flags as element that structures the conceptual voice within the piece and places it in a parodic and inter-textual tone. In this case, the choice of the USA flag as main reference is not at all casual. Thus, a dialogue is reactivated with Jaspers Johns that serves, in the first place, to narrate the experience of several generations of Cubans who have had to assume it as a demonized symbol, on the one hand, and as the flag that has sheltered them during a long exile, on the other.

In essence, the main value of this exploration is related to the ability to go beyond the confrontation between empire and island to inscribe the people’s feelings as a cultural and anthropological footprint, a sediment or substrate that goes beyond the most visible part of the day-to-day.

This last stage of his creation takes place to some extent from the diaspora; this circumstance favors the substantial increase in the use of the already mentioned parody, making it a more comprehensive resource with surprising capacity to associate elements from different realities, but thanks to his sharp ingenuity they start producing two metaphors.

I am referring to images that often speak of one or several stigmas (marks, and even debts); uncertainty, how to advance, restart, join the Faith, optimism and “happiness”, knowing that you are moving away from an extremely unique condition that has fluctuated excessively behind the always dangerous bow of an extremist ideology. In them, nostalgia is fixed as a symptom that cannot be ignored, a breath that forcefully launches some questions, among which stands out: how to make this nostalgia an edifying force or energy?

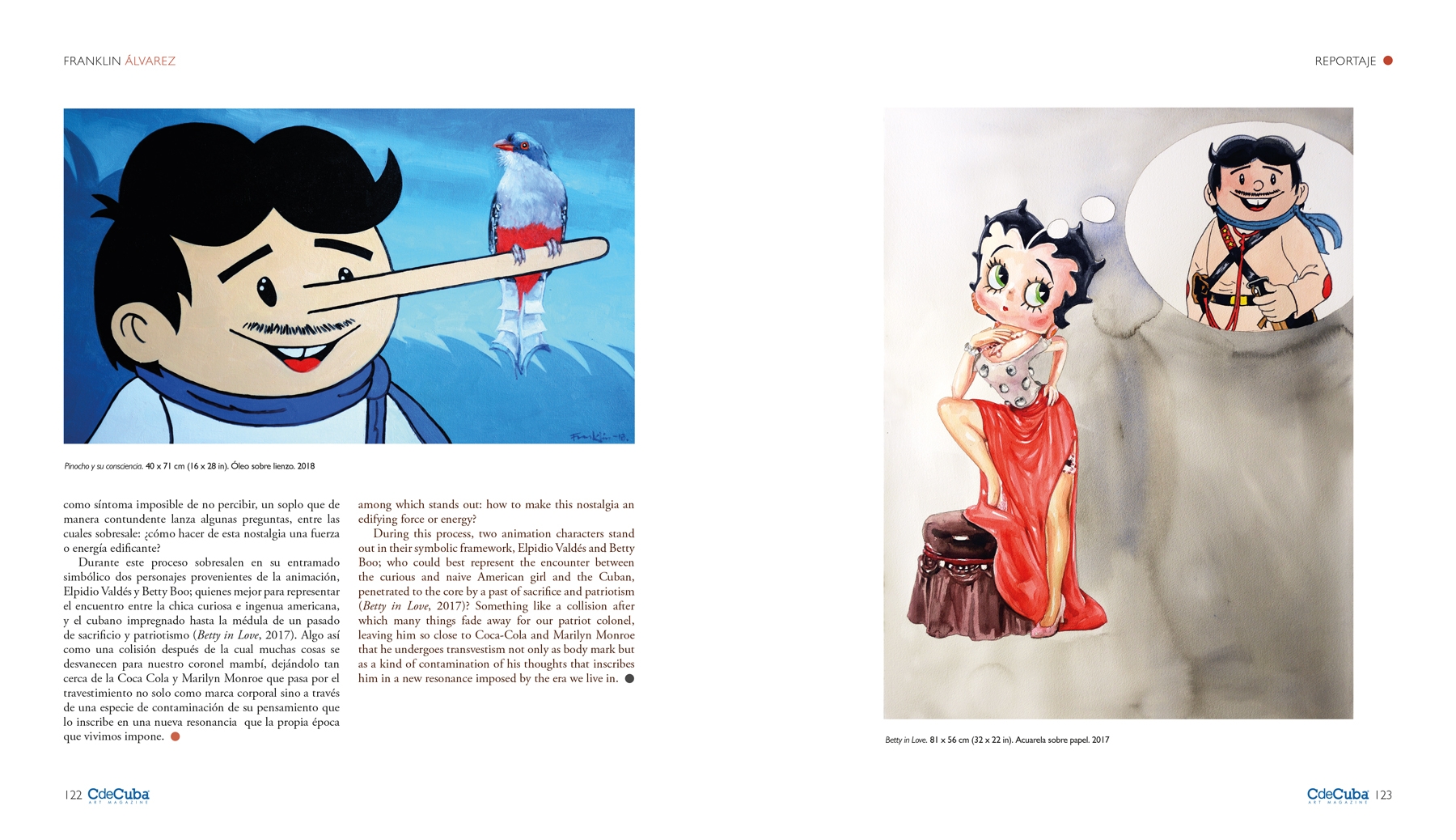

During this process, two animation characters stand out in their symbolic framework, Elpidio Valdés and Betty Boo; who could best represent the encounter between the curious and naive American girl and the Cuban, penetrated to the core by a past of sacrifice and patriotism (Betty in Love, 2017)? Something like a collision after which many things fade away for our patriot colonel, leaving him so close to Coca-Cola and Marilyn Monroe that he undergoes

transvestism not only as body mark but as a kind of contamination of his thoughts that inscribes him in a new resonance imposed by the era we live in.