Feeling Art in the Skin

By Shirley Moreira

The work of Gertrudis Rivalta (Santa Clara, 1971) has a special magic that makes it as delicate as it is energetic. At the moment of creation, the technique is at the mercy of the compositional will to reveal a world of sensations; therefore, there is no way to pigeonhole it into immovable aesthetic patterns. She is an artist of drawing, photography, painting, performance, installation… because in each medium she finds a particular way of translating her ideas with the sole purpose of connecting with the receiver and making her way through her fables.

The nineties would see her glean in Cuba as part of that batch of artists that resisted and grew in spite of the adversities, rethinking problems and diverse ways of feeling creation. In Queloides, one of the group exhibitions in which she participated after graduating from the Higher Institute of Art (ISA) in 1996, it is possible to see her early commitment to the great themes associated with identity and the study of negritude as racial heritage and means of connecting with other realities.

Self-reference takes on an important role in her discourse, since it always starts from her roots, her life, her experiences, her condition as a Cuban and mulatto woman. But there is no linear or evocative autobiography of univocal reality here. She uses her body at times, at others she unfolds her conceptions of the collective idiosyncrasy to arrive at particular identities. More than gender and race, the artist examines the processes of identity construction from the need to look at the other as an ideal means of understanding and accepting ourselves.

She also focuses her attention on society and the plots that shape it; on the historical, social and economic relations that are created between individuals. Sometimes she appeals to the Afro-Cuban religion as another means of understanding culture. However, she moves away from any folkloric idea because she seeks to break canons and elaborate images of the “other’s” identity, thus entering into the symbolic wealth of her iconography. She assumes the myths and rites as a means of connection with the roots of a nation and the distinctive features of its people.

In Un paseo con Walker Evans (1997), one of her first personal exhibitions, he shows more clearly his concrete modus operandi by mixing visual art reinterpretations of the photographs that Evans took in Cuba in the 1930s with images of popular characters. Rivalta starts from the American photographer’s distant vision in order to dialogue on the subject of stereotypes, the others’ view and the assignment of preconceived roles based on race or social position. Another guideline established in this exhibition was the choice of working mostly from series, half of which offered the possibility of fully unfolding the idea and leading it slowly to a happy ending.

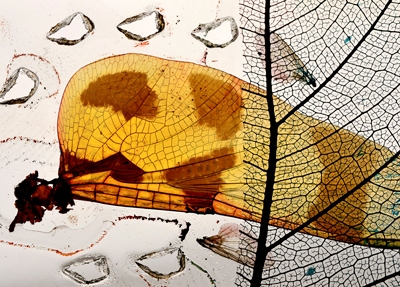

Among the series she has produced, we can find Fantasmas de azúcar (Sugar Ghosts), dedicated to the process of closing down many sugar mills in Cuba. It includes works that speak with nostalgia about the loss of identity, the failure or the end of the great utopias. For that reason she uses mud, blood, sugar, and coffee in their elaboration, reinforcing the sense of pain and uprooting. In Fnimaniev she recalls the dynamics of life of an entire people settled in the warm lap of the socialist countries; and in The Black Monkey on its Journey into Outer Space and Imagined, but the Truth Was Dreamed of, she focuses on the imagery generated by the publications of the sixties and seventies in the island. She takes as starting point magazines covers of Bohemia, Muchachas or Mujeres to talk about aesthetic models that they tried to “sow” in the collective image based on a predilection for foreign paradigms. Gertrudis questions (because her work is essentially based on questioning) the consolidation processes of a simulated and imported image with the consequent loss of identity patterns.

Five Variations of the Heart Trying to Understand History was a series exhibited as part of the Con Razón exhibition at the Development Center for the Visual Arts. In it, the artist visits again, by way of metaphors and with exquisite painting technique, historical moments of the Cuban nation. The heart, deprived of its context and made to dialogue with dissimilar elements, becomes a symbol of the unity of an entire society that is being shaped along the paths of its history. About this work the artist says: “I was recently told that the series Five Hearts… was a change in my discourse because it did not speak of race or gender. Well, is there anything that makes us more equal than a heart devoid of any organ, devoid of skin and its color? How is the heart of a black man different from that of a man of any race? Is it not an equalizing element to represent an individual by a part of him in which race or gender has no influence? Therefore, what I am is present in my work, despite what I am, is a tricky reality, since it is variable and made up by many other realities”. (1)

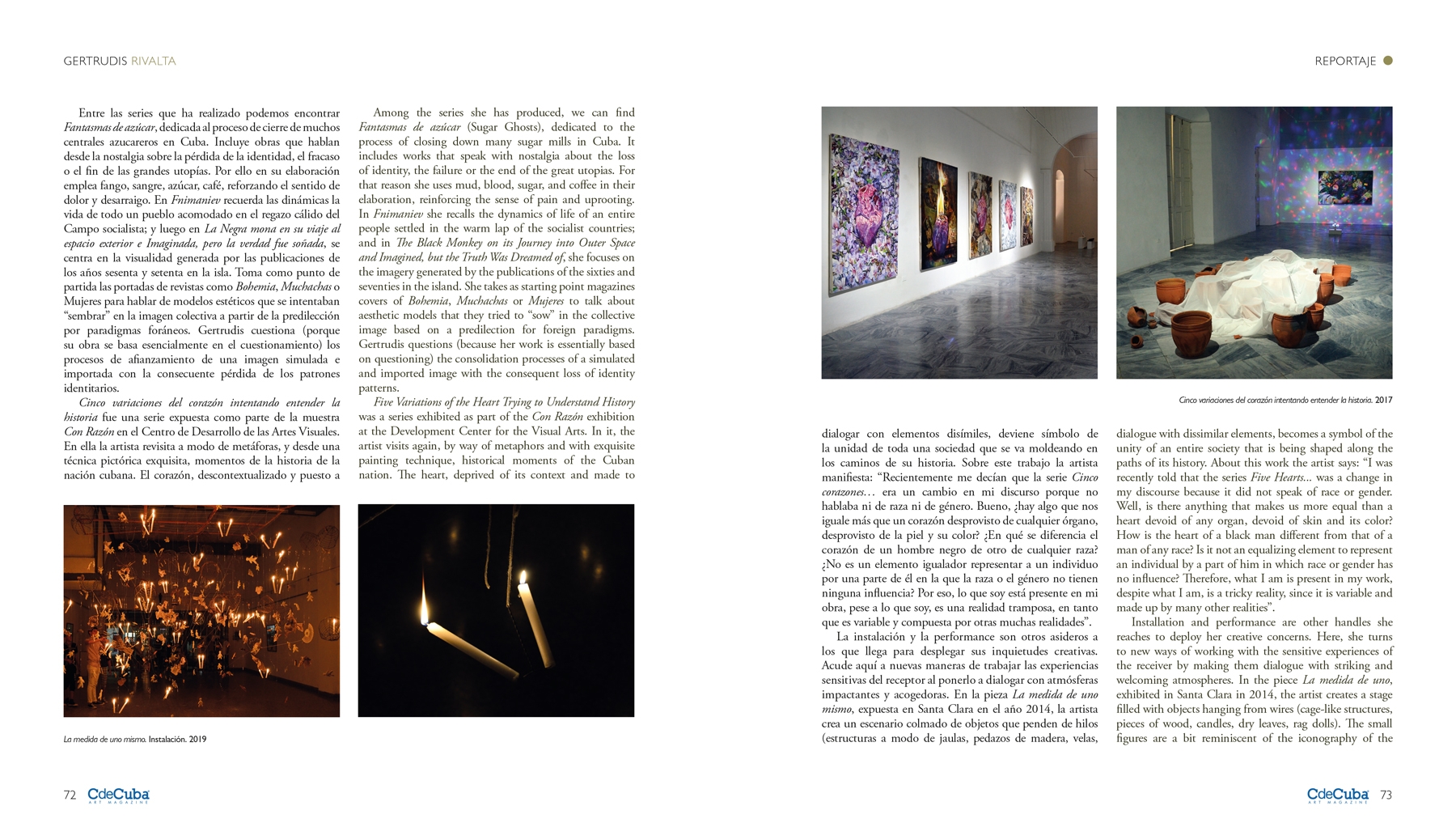

Installation and performance are other handles she reaches to deploy her creative concerns. Here, she turns to new ways of working with the sensitive experiences of the receiver by making them dialogue with striking and welcoming atmospheres. In the piece La medida de uno, exhibited in Santa Clara in 2014, the artist creates a stage filled with objects hanging from wires (cage-like structures, pieces of wood, candles, dry leaves, rag dolls). The small figures are a bit reminiscent of the iconography of the sympathetic magic of voodoo, in the desire to completely transfer human nature to the fabric figure. In this way she makes us feel part of the work and we find there the dynamics of our daily life.

In her most recent show Nubes del desierto (Albacete, 2019), the artist continues to show us her sensitivity to human problems and the vision that society imposes on others. Based on works executed a few years ago, Rivalta dialogues on the dramas of emigration, taking as a starting point the continuous wandering of people through the African desert clinging to the desire of a better future.

In performance she starts from her body, and from the self-referential component she reaches a number of realities. She recreates once again not only the problems associated with gender and race that are so typical of them, but also the visual dynamics of society and the ways of understanding culture. Such is the case of actions like Leningrad or Detaching My White Part.

Rivalta is a woman of the world. She prefers to say that she lives between Cuba and Spain, because although she took up residence in the European country many years ago, she always returns to her roots. Even though the international artistic, social, economic or political context in which she develops may permeate her way of facing the artistic fact, Cuba is her eternal starting point. Unfortunately, accounts of Cuban art are not only full of great names, but also of unjustified grandiloquence and sad omissions. Gertrudis Rivalta is one of those names that have moved between international fame and the relative silence of her land. But the artist is not afraid of silence. She knows that her work is a deafening cry in the mist; she knows that Cuba is also her way of feeling art, of evoking her roots, and knowing her history. Her work emerges from the island, and always returns to it in an infinite cycle, like a urodele that bites its own tail.

- Close to Gertrudis Rivalta’s visual universe. Interview by TR for TRMEstudio. In http://trmestudio.com/cercania-al-universo–visual-de-gertrudis-rivalta-oliva August, 2018