Atlantis

By Maikel José Rodríguez Calviño

I have in front of me the series On the Shoulder, by Leonardo Gutiérrez. The artist sent them to me via e-mail. It is a set of photographs that attract my attention. Before I started writing these lines, I observed them in detail, got away from my laptop and made coffee, went back to the screen and studied them once more. Then I put them aside, enjoyed a second cup of coffee, returned to them for the umpteenth time…

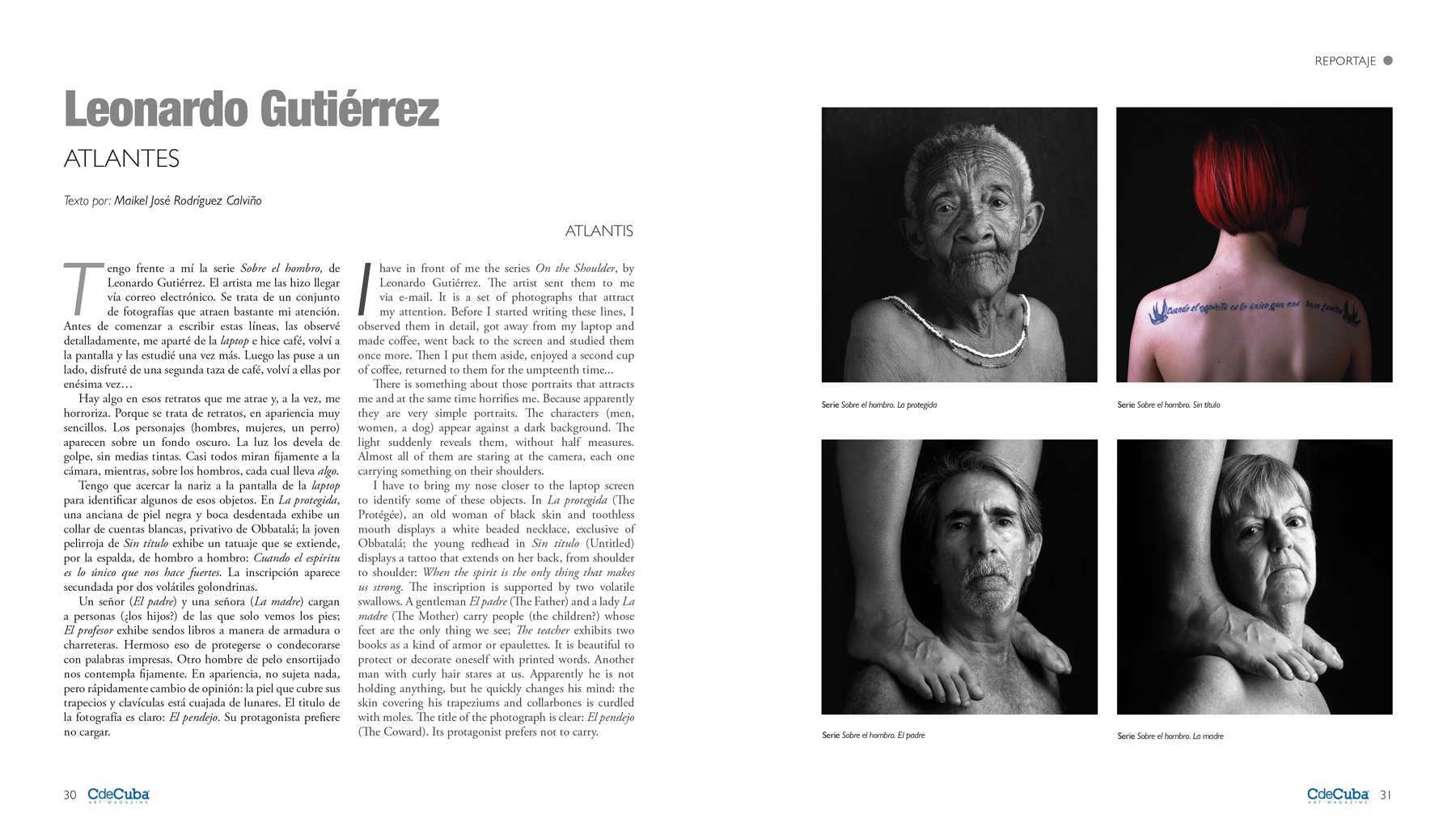

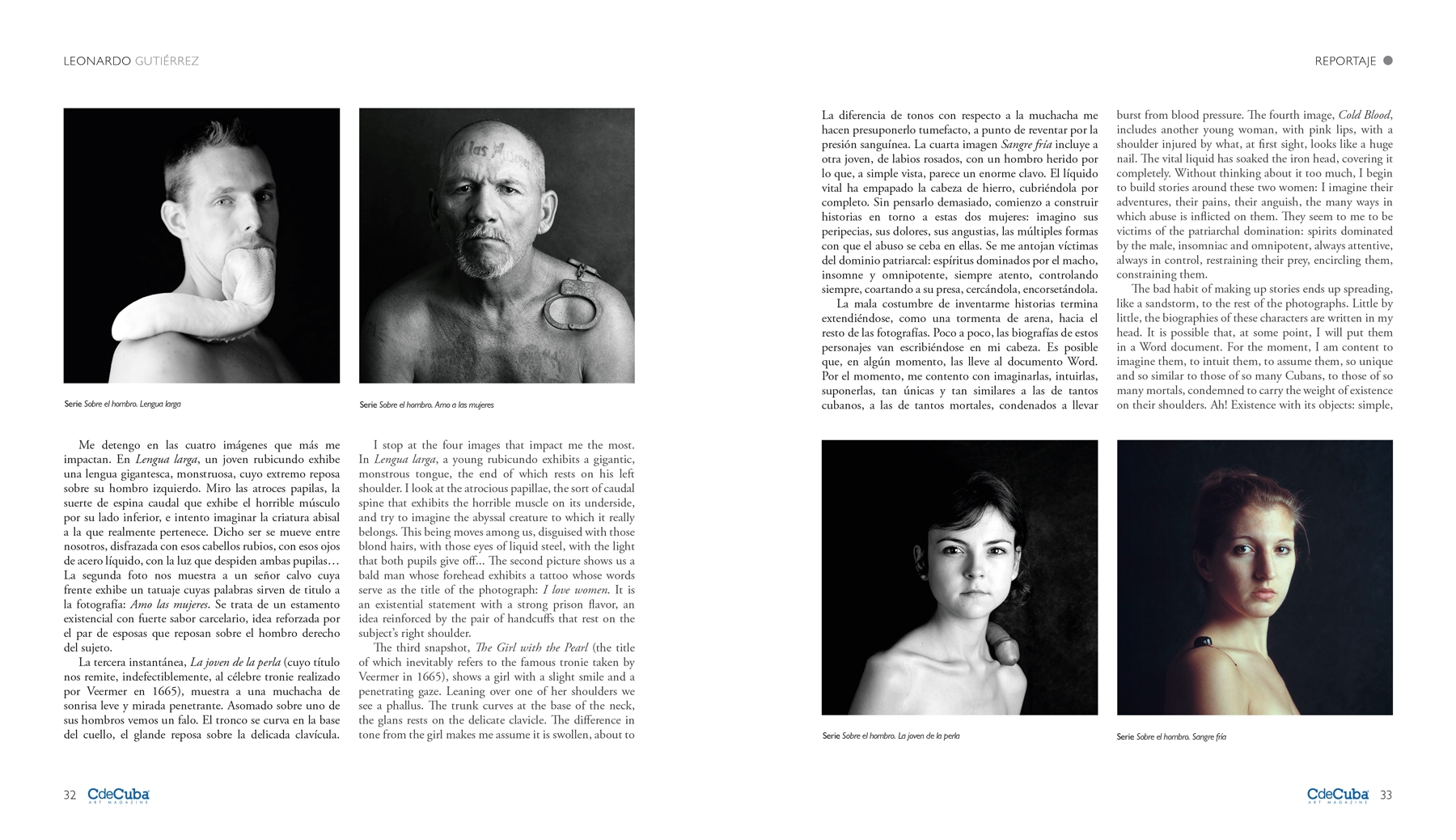

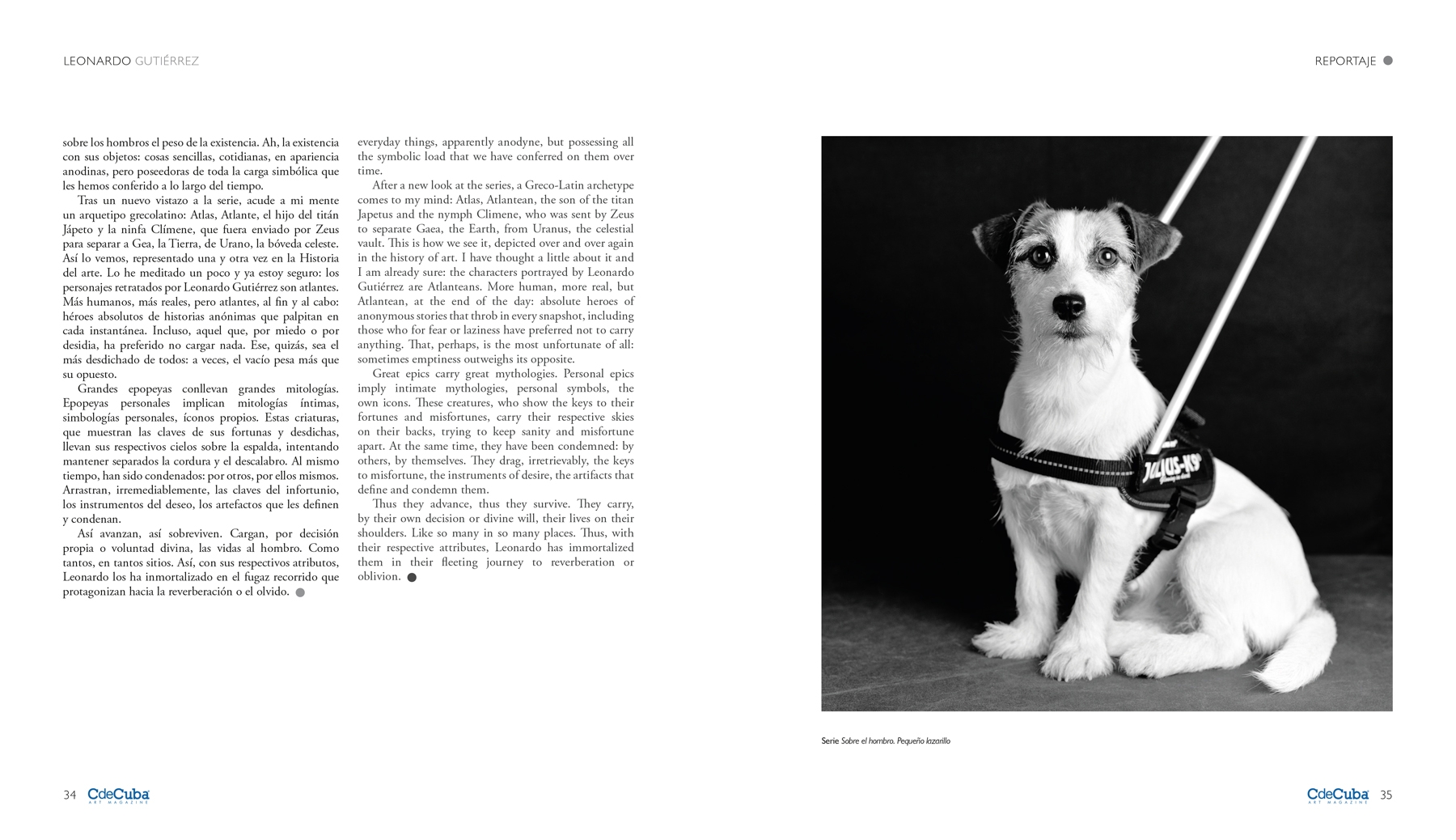

There is something about those portraits that attracts me and at the same time horrifies me. Because apparently they are very simple portraits. The characters (men, women, a dog) appear against a dark background. The light suddenly reveals them, without half measures. Almost all of them are staring at the camera, each one carrying something on their shoulders.

I have to bring my nose closer to the laptop screen to identify some of these objects. In La protegida (The Protégée), an old woman of black skin and toothless mouth displays a white beaded necklace, exclusive of Obbatalá; the young redhead in Sin título (Untitled) displays a tattoo that extends on her back, from shoulder to shoulder: When the spirit is the only thing that makes us strong. The inscription is supported by two volatile swallows. A gentleman El padre (The Father) and a lady La madre (The Mother) carry people (the children?) whose feet are the only thing we see; The teacher exhibits two books as a kind of armor or epaulettes. It is beautiful to protect or decorate oneself with printed words. Another man with curly hair stares at us. Apparently he is not holding anything, but he quickly changes his mind: the skin covering his trapeziums and collarbones is curdled with moles. The title of the photograph is clear: El pendejo (The Coward). Its protagonist prefers not to carry.

I stop at the four images that impact me the most. In Lengua larga, a young rubicundo exhibits a gigantic, monstrous tongue, the end of which rests on his left shoulder. I look at the atrocious papillae, the sort of caudal spine that exhibits the horrible muscle on its underside, and try to imagine the abyssal creature to which it really belongs. This being moves among us, disguised with those blond hairs, with those eyes of liquid steel, with the light that both pupils give off… The second picture shows us a bald man whose forehead exhibits a tattoo whose words serve as the title of the photograph: I love women. It is an existential statement with a strong prison flavor, an idea reinforced by the pair of handcuffs that rest on the subject’s right shoulder.

The third snapshot, The Girl with the Pearl (the title of which inevitably refers to the famous tronie taken by Veermer in 1665), shows a girl with a slight smile and a penetrating gaze. Leaning over one of her shoulders we see a phallus. The trunk curves at the base of the neck, the glans rests on the delicate clavicle. The difference in tone from the girl makes me assume it is swollen, about to burst from blood pressure. The fourth image, Cold Blood, includes another young woman, with pink lips, with a shoulder injured by what, at first sight, looks like a huge nail. The vital liquid has soaked the iron head, covering it completely. Without thinking about it too much, I begin to build stories around these two women: I imagine their adventures, their pains, their anguish, the many ways in which abuse is inflicted on them. They seem to me to be victims of the patriarchal domination: spirits dominated by the male, insomniac and omnipotent, always attentive, always in control, restraining their prey, encircling them, constraining them.

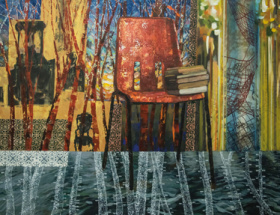

The bad habit of making up stories ends up spreading, like a sandstorm, to the rest of the photographs. Little by little, the biographies of these characters are written in my head. It is possible that, at some point, I will put them in a Word document. For the moment, I am content to imagine them, to intuit them, to assume them, so unique and so similar to those of so many Cubans, to those of so many mortals, condemned to carry the weight of existence on their shoulders. Ah! Existence with its objects: simple, everyday things, apparently anodyne, but possessing all the symbolic load that we have conferred on them over time.

After a new look at the series, a Greco-Latin archetype comes to my mind: Atlas, Atlantean, the son of the titan Japetus and the nymph Climene, who was sent by Zeus to separate Gaea, the Earth, from Uranus, the celestial vault. This is how we see it, depicted over and over again in the history of art. I have thought a little about it and I am already sure: the characters portrayed by Leonardo Gutiérrez are Atlanteans. More human, more real, but Atlantean, at the end of the day: absolute heroes of anonymous stories that throb in every snapshot, including those who for fear or laziness have preferred not to carry anything. That, perhaps, is the most unfortunate of all: sometimes emptiness outweighs its opposite.

Great epics carry great mythologies. Personal epics imply intimate mythologies, personal symbols, the own icons. These creatures, who show the keys to their fortunes and misfortunes, carry their respective skies on their backs, trying to keep sanity and misfortune apart. At the same time, they have been condemned: by others, by themselves. They drag, irretrievably, the keys to misfortune, the instruments of desire, the artifacts that define and condemn them.

Thus they advance, thus they survive. They carry, by their own decision or divine will, their lives on their shoulders. Like so many in so many places. Thus, with their respective attributes, Leonardo has immortalized them in their fleeting journey to reverberation or oblivion.