Restless Painting

By Dayneris Brito

During the 1990s, while visual artists were growing like bad weed and the economic crisis was causing countless waves of migration, a generation emerged halfway through the late 1980s and early 1990s scattered and preferred to emigrate and continue its creative work outside the island. Nevertheless, the spirit in which this wave of artists was formed, beyond the ideological and geographical borders that separated one from the other, continued to have common codes in terms of the way in which they assumed the art forms, and created awareness of the demarcation of a historical and social period, based on common patterns of reading and interpreting their reality. Transversally, their visual production was marked by disenchantment and ideological opposition, which led to the loss of their reference point and to the complex and metaphorical nature of the artistic registers involved.

The artistic object per se was modified, leaning towards a type of isolated and referential signifier that began to be camouflaged under semiological forms of art, echoing in the different supports, formats, genres and topics used at the time. Michel Blázquez (Havana, 1972), like any disciple of his generation, incorporates into his aesthetic imprint the features of a decade in which the artistic was defined in the premises of social satire and tropical density, according to Rufo Caballero, preserving in essence two of the creative paths that characterized his contemporaries: the use of metaphors in the aesthetic work and the reintroduction of the technique.

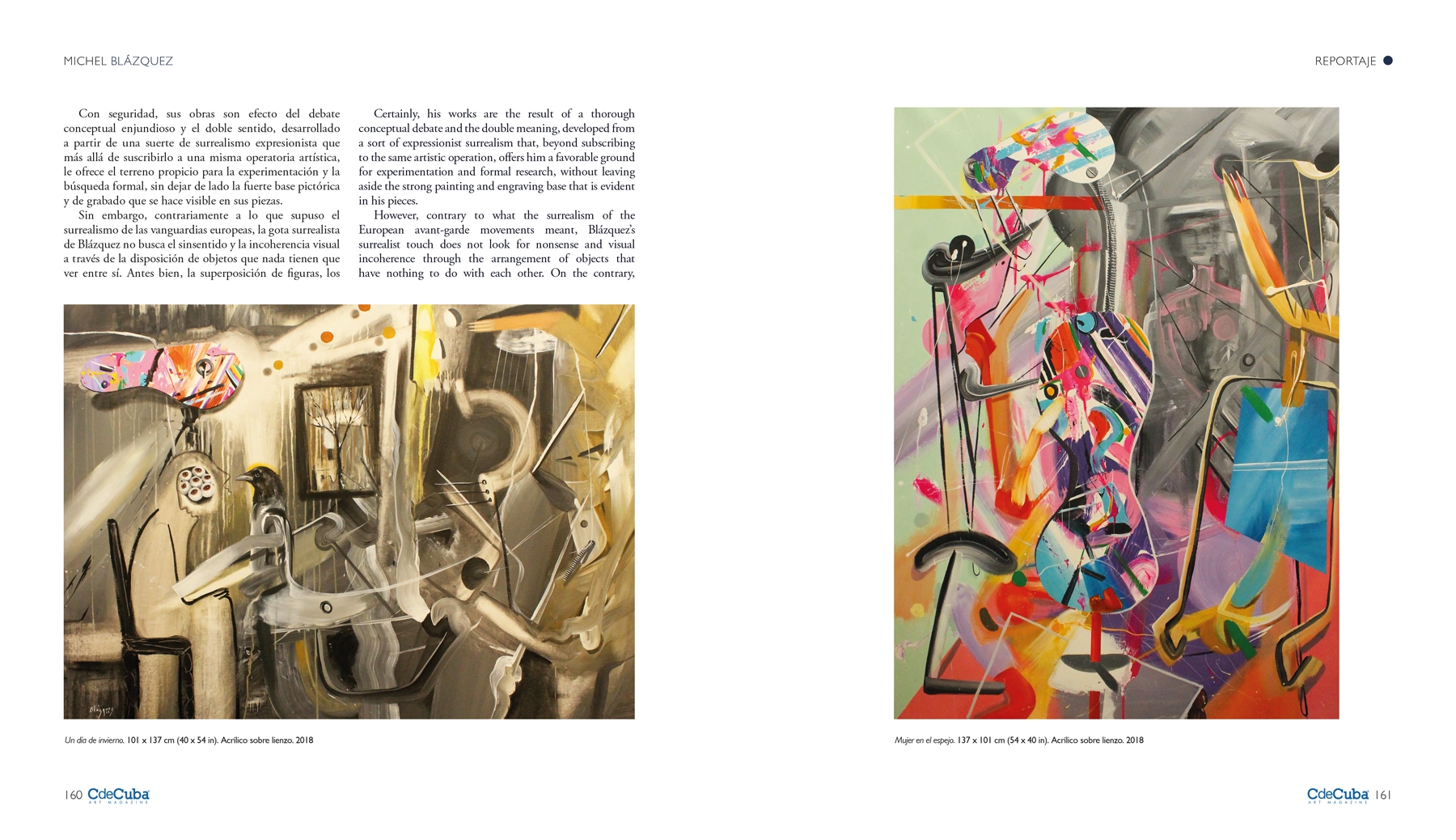

Certainly, his works are the result of a thorough conceptual debate and the double meaning, developed from a sort of expressionist surrealism that, beyond subscribing to the same artistic operation, offers him a favorable ground for experimentation and formal research, without leaving aside the strong painting and engraving base that is evident in his pieces.

However, contrary to what the surrealism of the European avant-garde movements meant, Blázquez’s surrealist touch does not look for nonsense and visual incoherence through the arrangement of objects that have nothing to do with each other. On the contrary, the superimposition of figures, isolated fragments, color stains and variegated decoration in fear of the void, work together as a result of a restless and incisive painting, which oscillates between dreamlike, fictional and caustic.

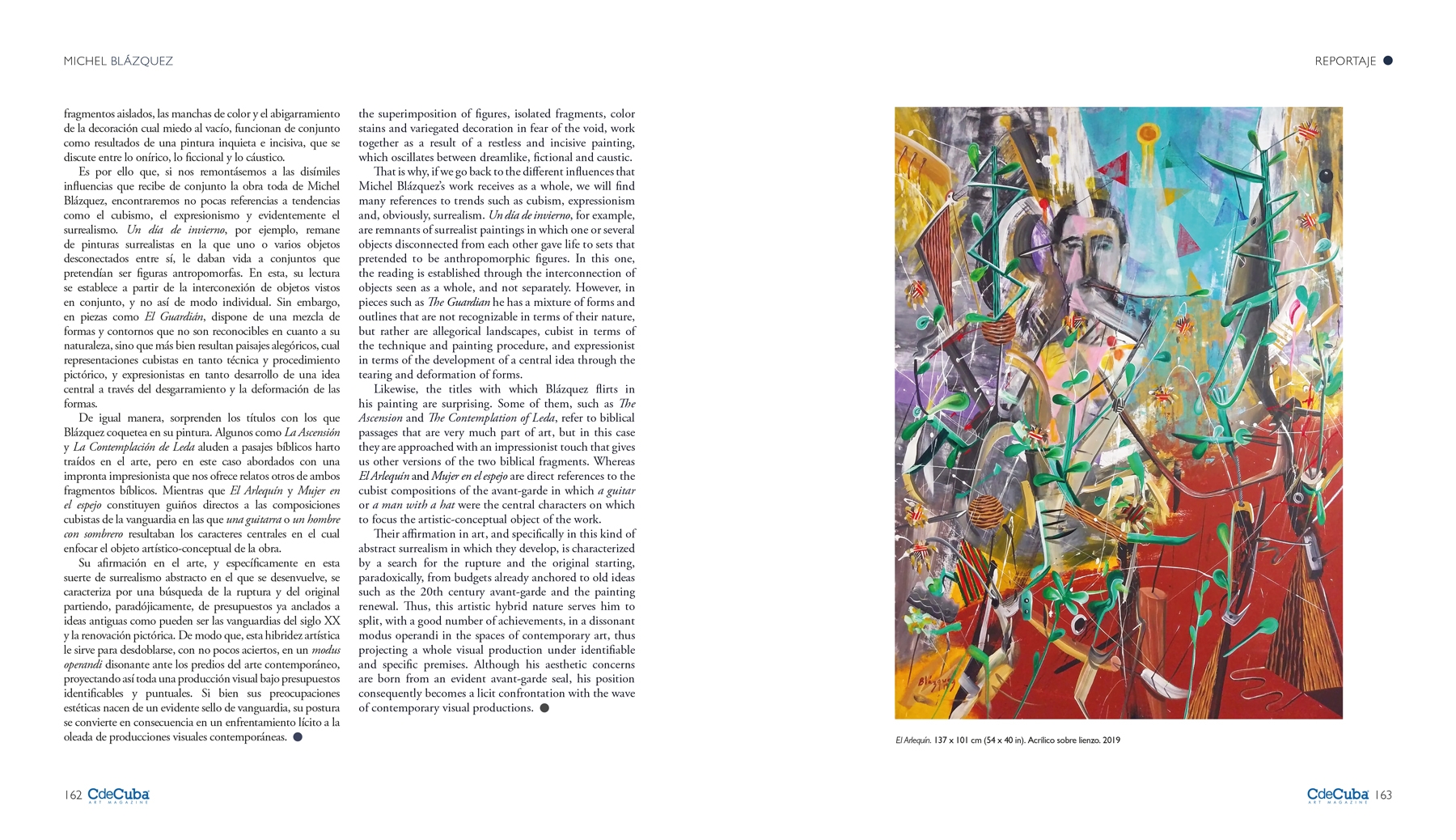

That is why, if we go back to the different influences that Michel Blázquez’s work receives as a whole, we will find many references to trends such as cubism, expressionism and, obviously, surrealism. The Others, for example, are remnants of surrealist paintings in which one or several objects disconnected from each other gave life to sets that pretended to be anthropomorphic figures. In this one, the reading is established through the interconnection of objects seen as a whole, and not separately. However, in pieces such as The Last Sigh he has a mixture of forms and outlines that are not recognizable in terms of their nature, but rather are allegorical landscapes, cubist in terms of the technique and painting procedure, and expressionist in terms of the development of a central idea through the tearing and deformation of forms.

Likewise, the titles with which Blázquez flirts in his painting are surprising. Some of them, such as The Ascension and The Contemplation of Leda, refer to biblical passages that are very much part of art, but in this case they are approached with an impressionist touch that gives us other versions of the two biblical fragments. Whereas Last Winter Sonata and The Guardian are direct references to the cubist compositions of the avant-garde in which a guitar or a man with a hat were the central characters on which to focus the artistic-conceptual object of the work.

Their affirmation in art, and specifically in this kind of abstract surrealism in which they develop, is characterized by a search for the rupture and the original starting, paradoxically, from budgets already anchored to old ideas such as the 20th century avant-garde and the painting renewal. Thus, this artistic hybrid nature serves him to split, with a good number of achievements, in a dissonant modus operandi in the spaces of contemporary art, thus projecting a whole visual production under identifiable and specific premises. Although his aesthetic concerns are born from an evident avant-garde seal, his position consequently becomes a licit confrontation with the wave of contemporary visual productions.