[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

At the Crossroads of Painting

By Suset Sanchez Sanchez

In his Notes on Today’s Painting from 1952, Jean Bazaine argued: “Painting, in these times of desperation is (…) a way of being: the temptation to breathe in an unbreathable world. The human being constantly asks painting for new evidences of its existence. And for the last fifty years it seems as if painting were in a feverish hurry to exhaust the means to provide them to him.” Indeed, since the post-war period, the continuous declarations of the death of painting have occurred with ever increasing frequency. In late 20th century and early 21st century, the painting languages have had to retreat into positions of resistance in order to compete with ever increasing sophisticated media that have displaced the viewers’ gaze and captured their attention. Meanwhile, the artists who continue to explore forms of persistence, narration, representation, and critique related to an immeasurable language such as that of painting have been compelled to reinforce their knowledge of the medium and deepen their historicist tradition in search of the keys that make it possible for painting and its expanded presences to continue to exist as device for the construction of the image in the post-media condition of the present.

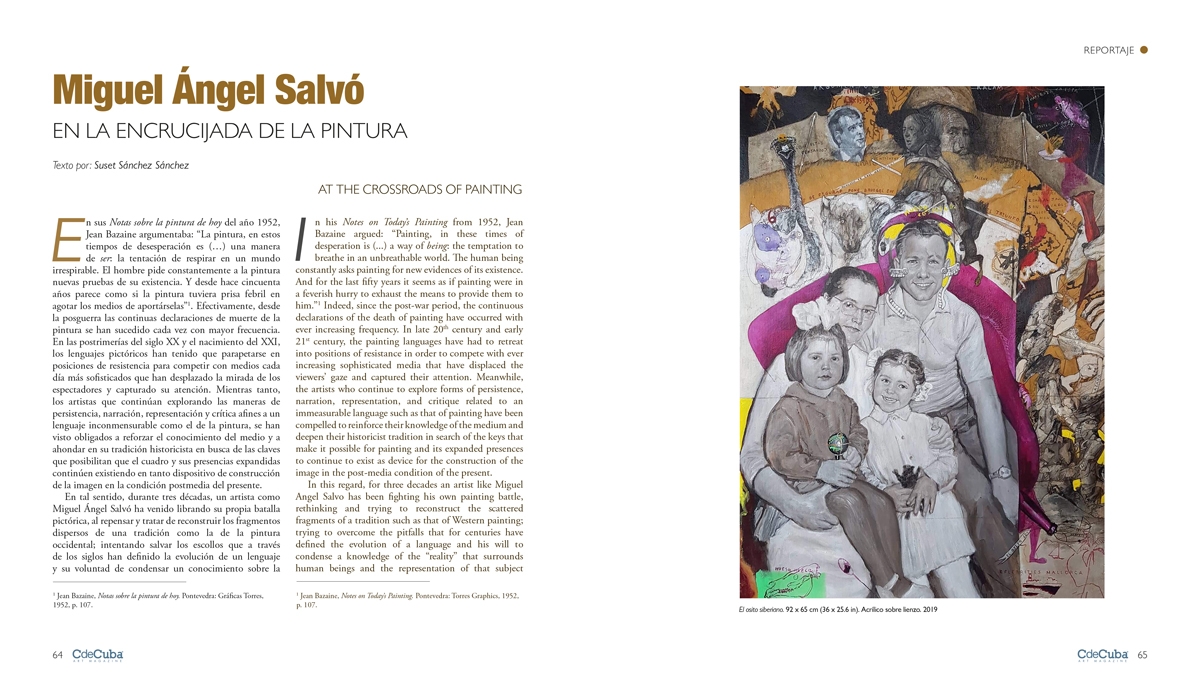

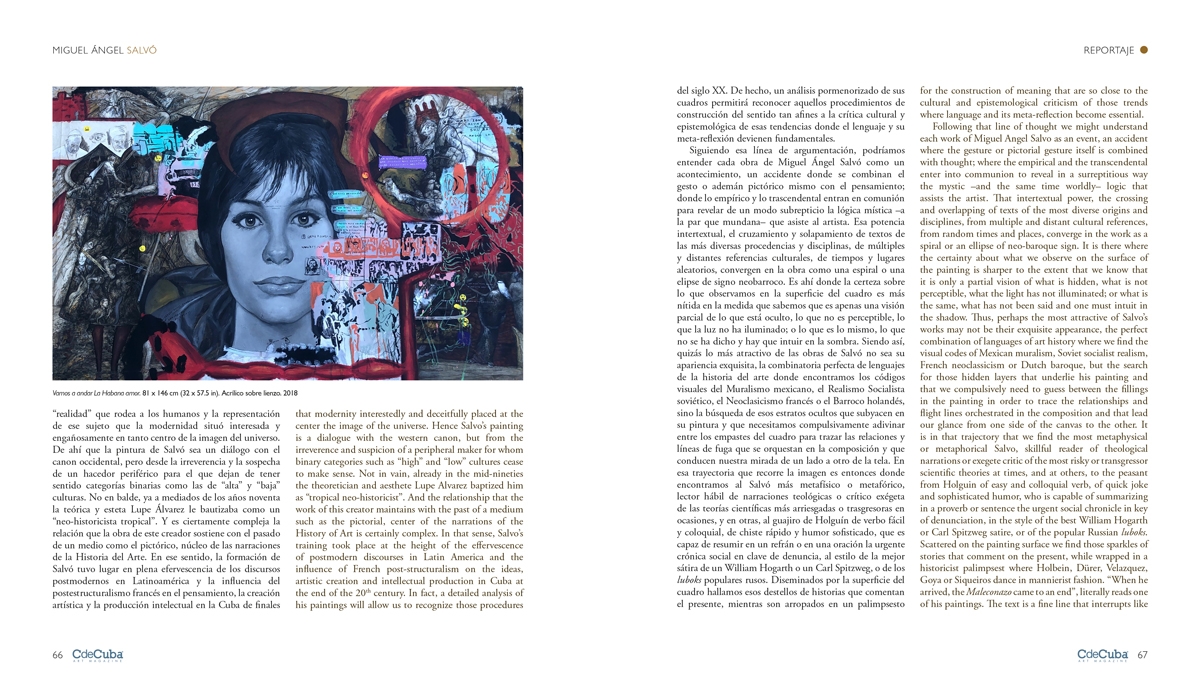

In this regard, for three decades an artist like Miguel Angel Salvo has been fighting his own painting battle, rethinking and trying to reconstruct the scattered fragments of a tradition such as that of Western painting; trying to overcome the pitfalls that for centuries have defined the evolution of a language and his will to condense a knowledge of the “reality” that surrounds human beings and the representation of that subject that modernity interestedly and deceitfully placed at the center the image of the universe. Hence Salvo’s painting is a dialogue with the western canon, but from the irreverence and suspicion of a peripheral maker for whom binary categories such as “high” and “low” cultures cease to make sense. Not in vain, already in the mid-nineties the theoretician and aesthete Lupe Alvarez baptized him as “tropical neo-historicist”. And the relationship that the work of this creator maintains with the past of a medium such as the pictorial, center of the narrations of the History of Art is certainly complex. In that sense, Salvo’s training took place at the height of the effervescence of postmodern discourses in Latin America and the influence of French post-structuralism on the ideas, artistic creation and intellectual production in Cuba at the end of the 20th century. In fact, a detailed analysis of his paintings will allow us to recognize those procedures for the construction of meaning that are so close to the cultural and epistemological criticism of those trends where language and its meta-reflection become essential.

Following that line of thought we might understand each work of Miguel Angel Salvo as an event, an accident where the gesture or pictorial gesture itself is combined with thought; where the empirical and the transcendental enter into communion to reveal in a surreptitious way the mystic –and the same time worldly– logic that assists the artist. That intertextual power, the crossing and overlapping of texts of the most diverse origins and disciplines, from multiple and distant cultural references, from random times and places, converge in the work as a spiral or an ellipse of neo-baroque sign. It is there where the certainty about what we observe on the surface of the painting is sharper to the extent that we know that it is only a partial vision of what is hidden, what is not perceptible, what the light has not illuminated; or what is the same, what has not been said and one must intuit in the shadow. Thus, perhaps the most attractive of Salvo’s works may not be their exquisite appearance, the perfect combination of languages of art history where we find the visual codes of Mexican muralism, Soviet socialist realism, French neoclassicism or Dutch baroque, but the search for those hidden layers that underlie his painting and that we compulsively need to guess between the fillings in the painting in order to trace the relationships and flight lines orchestrated in the composition and that lead our glance from one side of the canvas to the other. It is in that trajectory that we find the most metaphysical or metaphorical Salvo, skillful reader of theological narrations or exegete critic of the most risky or transgressor scientific theories at times, and at others, to the peasant from Holguin of easy and colloquial verb, of quick joke and sophisticated humor, who is capable of summarizing in a proverb or sentence the urgent social chronicle in key of denunciation, in the style of the best William Hogarth or Carl Spitzweg satire, or of the popular Russian luboks. Scattered on the painting surface we find those sparkles of stories that comment on the present, while wrapped in a historicist palimpsest where Holbein, Dürer, Velazquez, Goya or Siqueiros dance in mannierist fashion. “When he arrived, the Maleconazo came to an end,” literally reads one of his paintings. The text is a fine line that interrupts like an arrow the heroic packaging of the scene representing a grandiloquent, cultured, academic figuration, whose density is diminished by that earthly scream that smells of the street and of a present where the historical time is drowned out in order to return us to the pressures of social life in this ever more convulsive present. Perhaps the artist wants to signify that the lowercase stories that contravene the great official stories are precisely those that are written from the margins, on the margins, with the marginalized, and always on the margin of power.

In his own way, and without skimping on the complexity and convoluted intricacies of the narrative, Miguel Angel Salvo could be a painter of stories that are repeated cyclically to reveal the complicated human condition. Note that we prefer to speak of “stories” and not of a painting of history in the strict sense, although the artist incorporates into his compositions many of the formal characteristics that fixed this pictorial genre, especially the allegorical content and the use of parables, so similar to the religious representations of which Salvo is a profound scholar. Not in vain, in midst of the profusion of figures that inhabit his works, a bestiary emerges as moral repository that comments on that world in which the artist is condemned to exist and from which he cannot escape, because the mediated reality reaches him every second as constant bombardment of information without hierarchies and with many ideological filters that make him declare himself in permanent insurrection. Football, television, fashion, the local histories of the places he has lived in, such as Holguin, Havana or Mallorca; the ideas of Richard Dawkins, Galileo or Severo Sarduy coexist promiscuously in his canvases transforming the painting into a heterotopic space that becomes a different place in this over-saturated era of images and information. When the wolf of Little Red Riding Hood, Karl Lagerfeld’s cat, the ostriches and hutias that provide a protein utopia to the crazy discourse of political power in Cuba in times of economic recession and food crisis, or the Siberian husky –that Siberian dog breed, that geopolitical “coincidence”– rumored to be Raul Castro’s mascot, appear on his canvases, Salvo is questioning us through a discourse on ethics that places the historical commentary and the customs and manners anecdote in local and national landscapes.

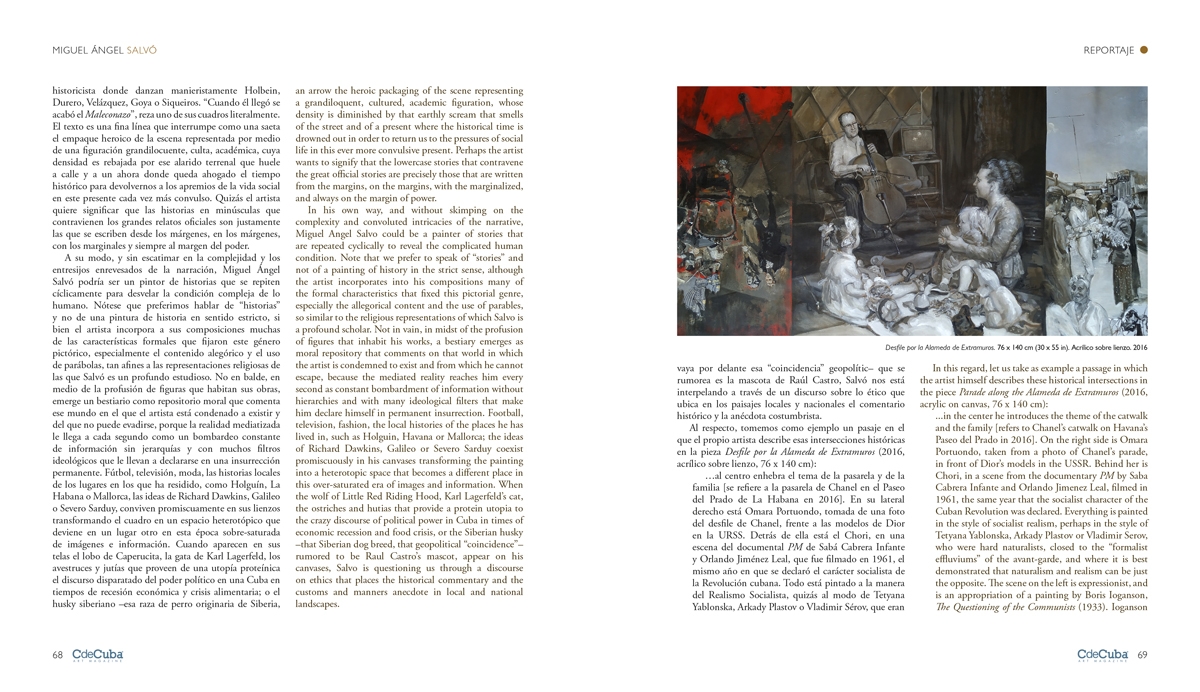

In this regard, let us take as example a passage in which the artist himself describes these historical intersections in the piece Parade along the Alameda de Extramuros (2016, acrylic on canvas, 81 x 146 cm):

…in the center he introduces the theme of the catwalk and the family [refers to Chanel’s catwalk on Havana’s Paseo del Prado in 2016]. On the right side is Omara Portuondo, taken from a photo of Chanel’s parade, in front of Dior’s models in the USSR. Behind her is Chori, in a scene from the documentary PM by Saba Cabrera Infante and Orlando Jimenez Leal, filmed in 1961, the same year that the socialist character of the Cuban Revolution was declared. Everything is painted in the style of socialist realism, perhaps in the style of Tetyana Yablonska, Arkady Plastov or Vladimir Sérov, who were hard naturalists, closed to the “formalist effluviums” of the avant-garde, and where it is best demonstrated that naturalism and realism can be just the opposite. The scene on the left is expressionist, and is an appropriation of a painting by Boris Ioganson, The Questioning of the Communists (1933). Ioganson went from defending constructivism to the darkest and demagogic socialist realism and pamphlet. I inverted the scene and turned it into a king Saul who tries to attack with a spear young David, future king of Israel (…). Jiménez Leal said that after the exhibition of PM at Casa de las Americas he read George Orwell’s novel 1984 and lived it. There were no boundaries between reality and fiction. In a lower corner of the painting there is also a reference to the famous barber’s lubok that tells about the reforms of Peter I. The veil of speaking obliquely of Cuba in my paintings is perhaps due to self-censorship…2

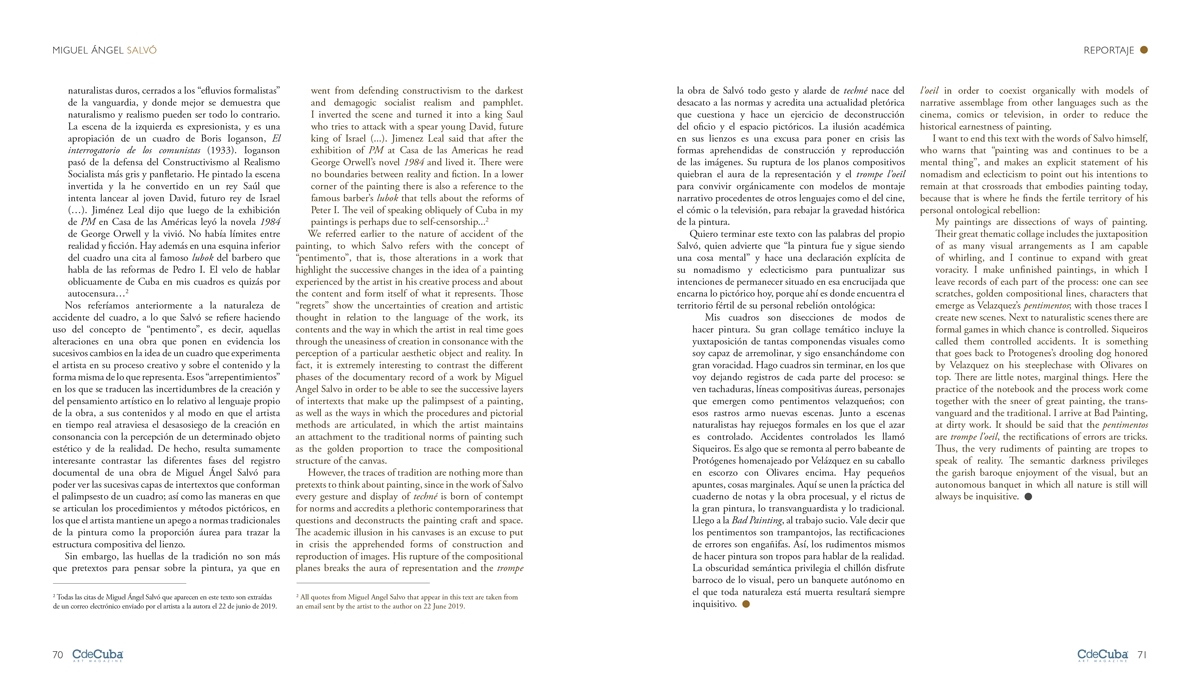

We referred earlier to the nature of accident of the painting, to which Salvo refers with the concept of “pentimento”, that is, those alterations in a work that highlight the successive changes in the idea of a painting experienced by the artist in his creative process and about the content and form itself of what it represents. Those “regrets” show the uncertainties of creation and artistic thought in relation to the language of the work, its contents and the way in which the artist in real time goes through the uneasiness of creation in consonance with the perception of a particular aesthetic object and reality. In fact, it is extremely interesting to contrast the different phases of the documentary record of a work by Miguel Angel Salvo in order to be able to see the successive layers of intertexts that make up the palimpsest of a painting, as well as the ways in which the procedures and pictorial methods are articulated, in which the artist maintains an attachment to the traditional norms of painting such as the golden proportion to trace the compositional structure of the canvas.

However, the traces of tradition are nothing more than pretexts to think about painting, since in the work of Salvo every gesture and display of techné is born of contempt for norms and accredits a plethoric contemporariness that questions and deconstructs the painting craft and space. The academic illusion in his canvases is an excuse to put in crisis the apprehended forms of construction and reproduction of images. His rupture of the compositional planes breaks the aura of representation and the trompe l’oeil in order to coexist organically with models of narrative assemblage from other languages such as the cinema, comics or television, in order to reduce the historical earnestness of painting.

I want to end this text with the words of Salvo himself, who warns that “painting was and continues to be a mental thing”, and makes an explicit statement of his nomadism and eclecticism to point out his intentions to remain at that crossroads that embodies painting today, because that is where he finds the fertile territory of his personal ontological rebellion:

My paintings are dissections of ways of painting. Their great thematic collage includes the juxtaposition of as many visual arrangements as I am capable of whirling, and I continue to expand with great voracity. I make unfinished paintings, in which I leave records of each part of the process: one can see scratches, golden compositional lines, characters that emerge as Velazquez’s pentimentos; with those traces I create new scenes. Next to naturalistic scenes there are formal games in which chance is controlled. Siqueiros called them controlled accidents. It is something that goes back to Protogenes’s drooling dog honored by Velazquez on his steeplechase with Olivares on top. There are little notes, marginal things. Here the practice of the notebook and the process work come together with the sneer of great painting, the trans-vanguard and the traditional. I arrive at Bad Painting, at dirty work. It should be said that the pentimentos are trompe l’oeil, the rectifications of errors are tricks. Thus, the very rudiments of painting are tropes to speak of reality. The semantic darkness privileges the garish baroque enjoyment of the visual, but an autonomous banquet in which all nature is still will always be inquisitive.

Artist’s Gallery[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]