Soma

By Carlos Jaime Jimenez

Hilda María Rodríguez Enríquez’s work unfolds between tension and balance. Or perhaps, in her case, both are one. Her creations tend to open a space in which violence, delicacy, lucid contemplation, eroticism, life and death drive coexist. The body holds a central place, and is represented in its palpitating materiality, rich in elastic forms and turgidity, expressed through refined strokes and a commendable drawing rigor. Sometimes, more than represented, the body is evoked, it ceases to be only pictorial or sculptural matter, and it is also a textual space, loaded with resonances and narrative potential.

In the last 15 years, Hilda María has been presenting the results of a long process of reflection on art, in which both her art and her prolific output in the field of criticism and curatorship are involved. Her work, however, is free of any academic urge. It is excessively marked by spontaneity and instinct to be constrained by over-intellectualization, or by the dictates associated with the discourse on art. In this sense, Hilda knows how to be both a judge and a party, but she assumes this with a vulnerability and ease from which her creations end up benefiting. The series Servando en mi pupila bears witness to this. It shows an artist who openly exhibits the master’s influence on her own creative sensitivity, without trying to justify or mediate that influence with ironic games that would be out of place. There is, however, self-awareness in relation to intertextual links, assumed in an honest and direct way. That is perhaps why when contemplating these pieces together with the rest of Hilda’s creations, their individual features shine more brightly, and the tribute to Servando is revealed above all as a means of channeling various very personal concerns in relation to the body as vehicle and at the same time as metaphor for erotic experience.

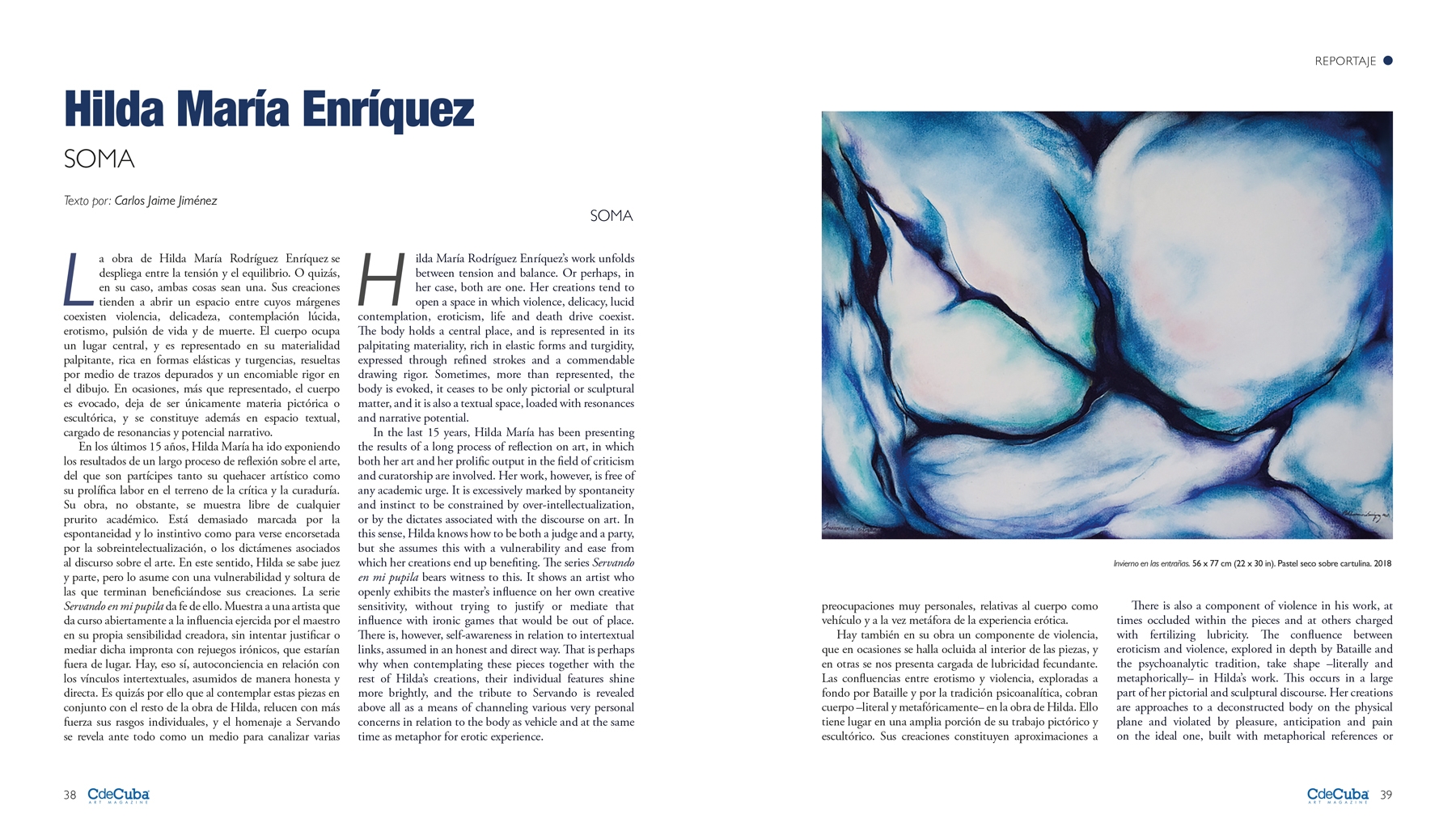

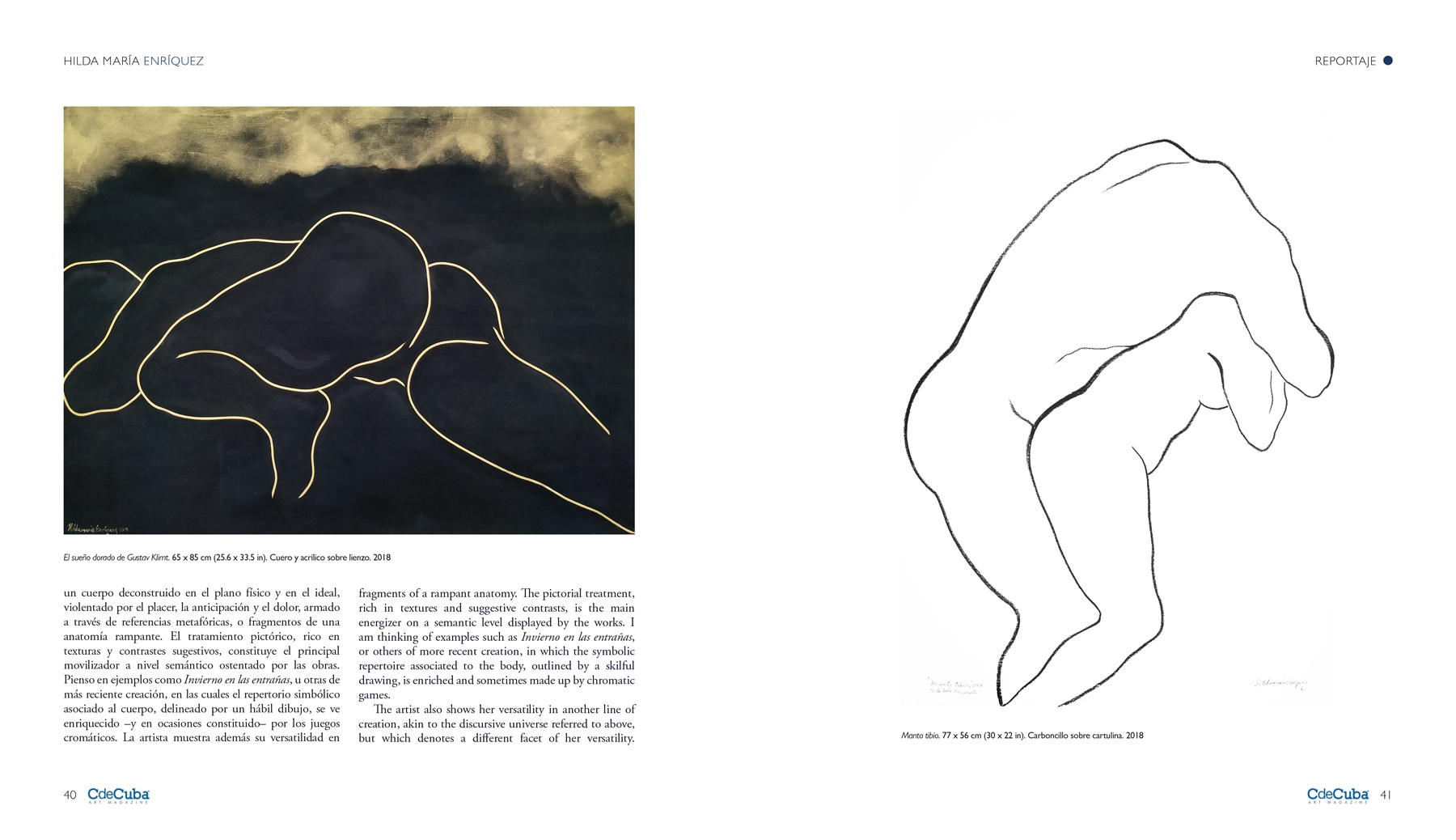

There is also a component of violence in his work, at times occluded within the pieces and at others charged with fertilizing lubricity. The confluence between eroticism and violence, explored in depth by Bataille and the psychoanalytic tradition, take shape -literally and metaphorically- in Hilda’s work. This occurs in a large part of her pictorial and sculptural discourse. Her creations are approaches to a deconstructed body on the physical plane and violated by pleasure, anticipation and pain on the ideal one, built with metaphorical references or fragments of a rampant anatomy. The pictorial treatment, rich in textures and suggestive contrasts, is the main energizer on a semantic level displayed by the works. I am thinking of examples such as Invierno en las entrañas, or others of more recent creation, in which the symbolic repertoire associated to the body, outlined by a skilful drawing, is enriched and sometimes made up by chromatic games.

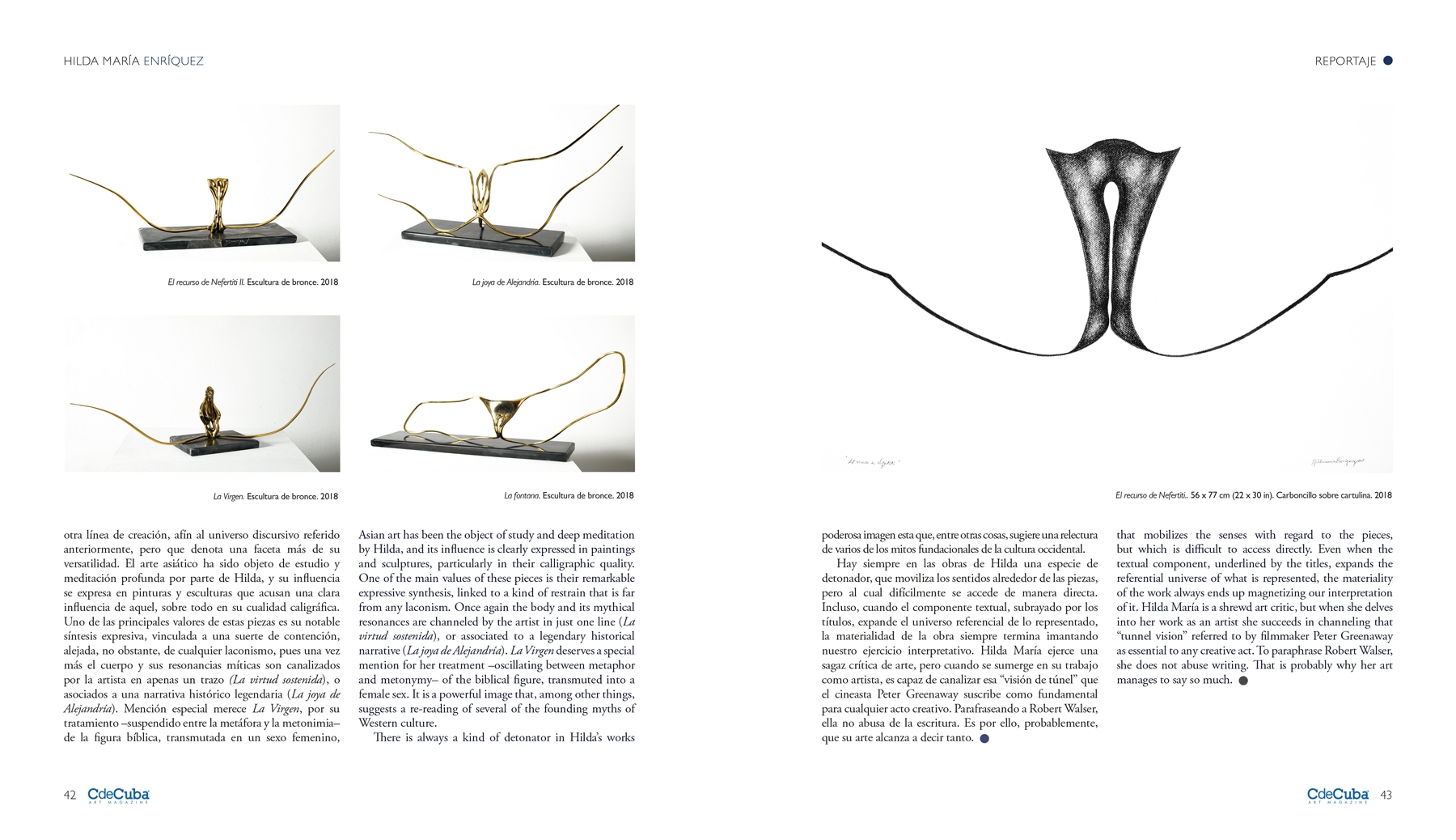

The artist also shows her versatility in another line of creation, akin to the discursive universe referred to above, but which denotes a different facet of her versatility. Asian art has been the object of study and deep meditation by Hilda, and its influence is clearly expressed in paintings and sculptures, particularly in their calligraphic quality. One of the main values of these pieces is their remarkable expressive synthesis, linked to a kind of restrain that is far from any laconism. Once again the body and its mythical resonances are channeled by the artist in just one line (La virtud sostenida), or associated to a legendary historical narrative (La joya de Alejandría). La Virgen deserves a special mention for her treatment –oscillating between metaphor and metonymy– of the biblical figure, transmuted into a female sex. It is a powerful image that, among other things, suggests a re-reading of several of the founding myths of Western culture.

There is always a kind of detonator in Hilda’s works that mobilizes the senses with regard to the pieces, but which is difficult to access directly. Even when the textual component, underlined by the titles, expands the referential universe of what is represented, the materiality of the work always ends up magnetizing our interpretation of it. Hilda María is a shrewd art critic, but when she delves into her work as an artist she succeeds in channeling that “tunnel vision” referred to by filmmaker Peter Greenaway as essential to any creative act. To paraphrase Robert Walser, she does not abuse writing. That is probably why her art manages to say so much.