Art from Alienation

By Nathalie Mesa Sanchez

The English poet and historian Thomas Macaulay said: “Perhaps no one can be a poet, or even enjoy poetry, without a certain amount of alienation”, and I would add that alienation is inherent in the artist, since the depth attained by him reveals the quality of his work.

In the eagerness to create dramatic situations through painting, visual artist Leticia Sánchez succeeds in recovering that ideal intimacy offered by mental alienation. Her strategy is to appropriate, as she says film stills with the essential purpose of a technical search. Therefore, two essential elements interest this creator: concept and technique, both framed in a post-modernity that sometimes pretends to minimize the latter in a sort of harmful artistic laziness. However, Leticia should not be considered one of these artists, since she prefers to experiment with ways of doing through good work with oil, pastel, light boxes and different formats.

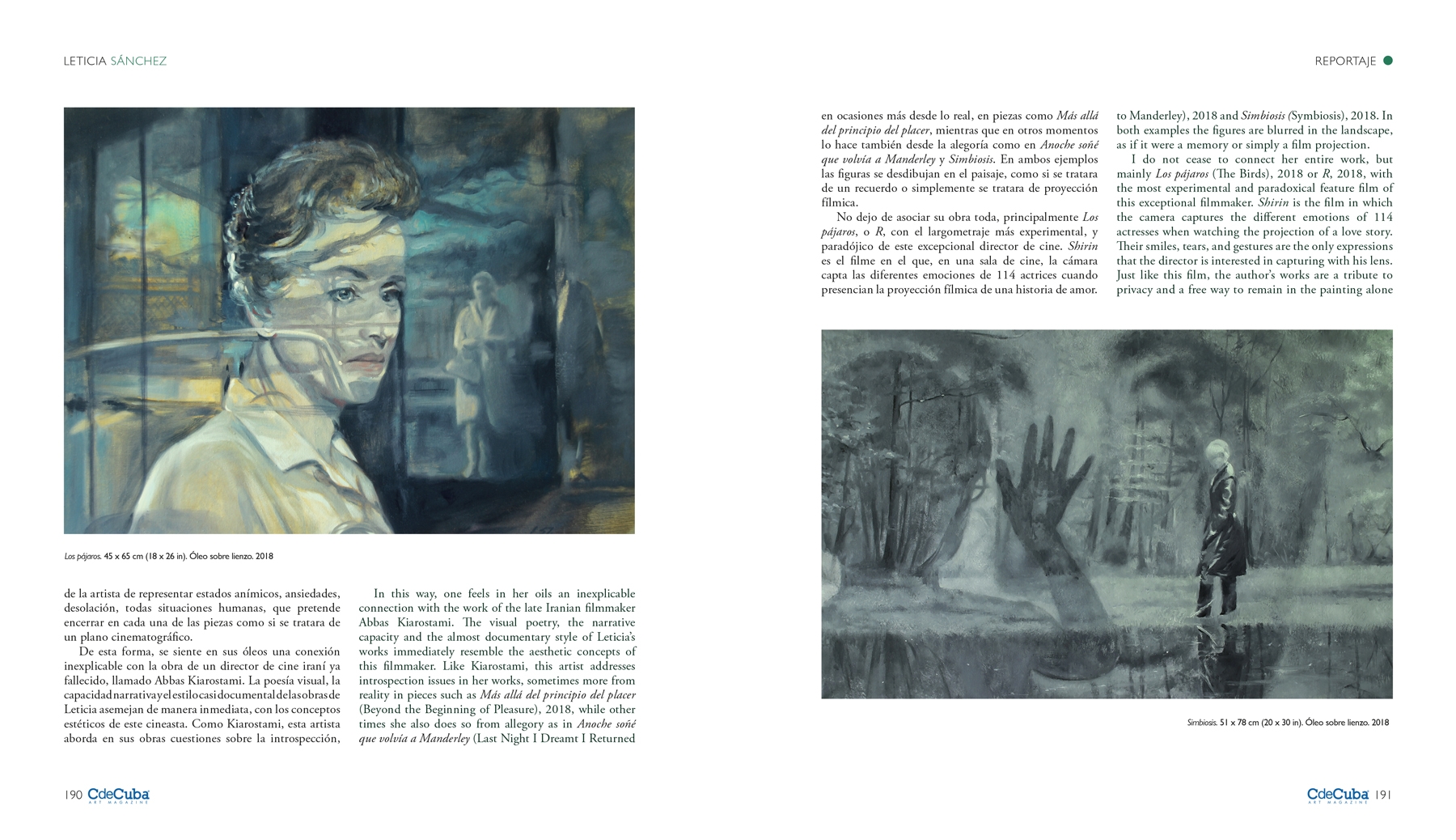

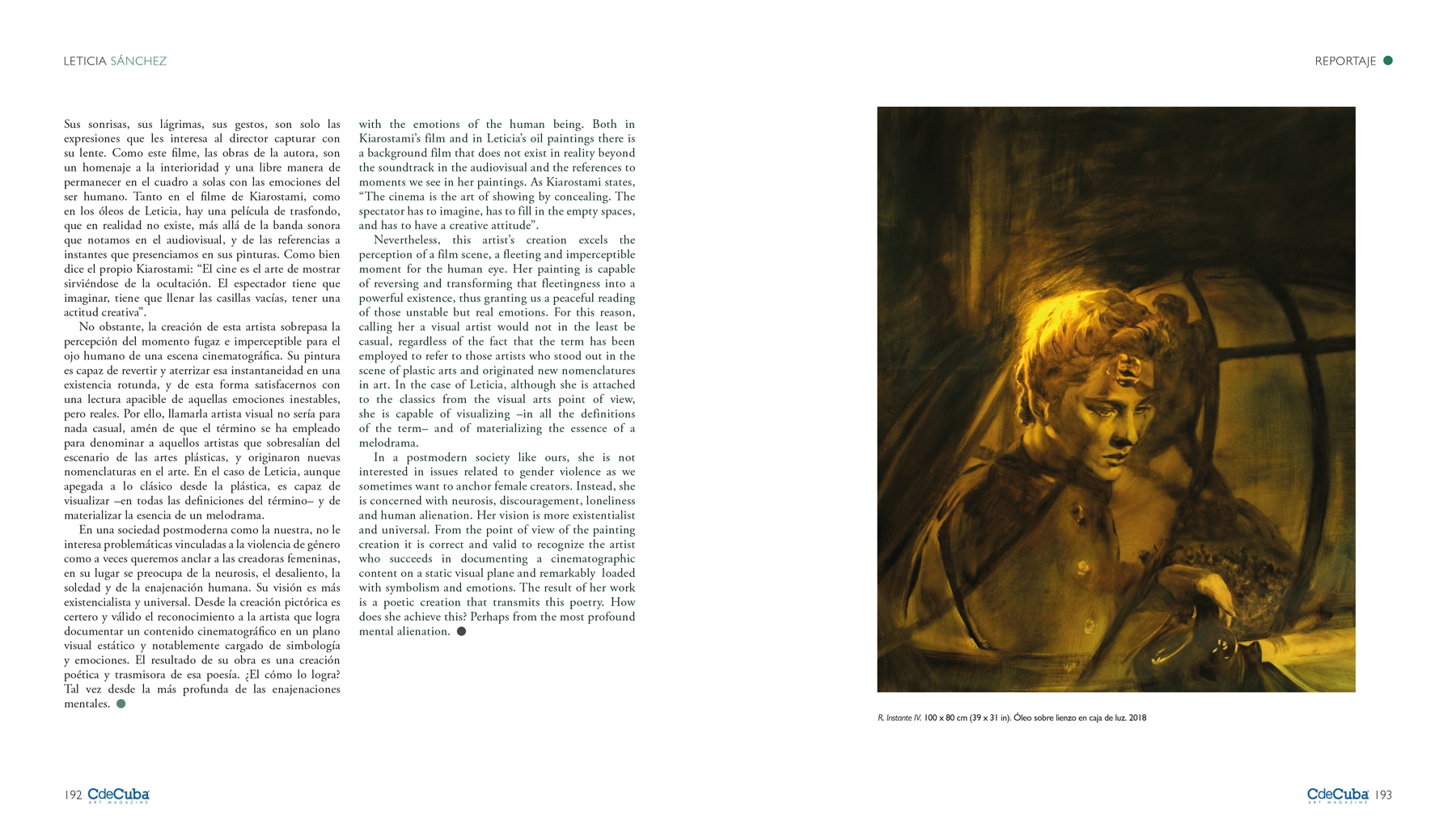

It is not in the least a cliché to say that her art procedure recalls the most classic impressionists, mainly due to the loose, short and thick brushstrokes of color, the desire to capture the fleeting moment, the images that seem out of focus, and the appearance of an unfinished work. Nevertheless, I do not intend to pigeonhole her production to a movement or style, since it is also striking to appreciate an expressionism that emerges from the color and from the brushstrokes that surround each figure. We would say that this last intention is more attached to the artist’s need to represent moods, anxieties, and desolation, all human situations that she tries to frame in each piece as if it were a film shot.

In this way, one feels in her oils an inexplicable connection with the work of the late Iranian filmmaker Abbas Kiarostami. The visual poetry, the narrative capacity and the almost documentary style of Leticia’s works immediately resemble the aesthetic concepts of this filmmaker. Like Kiarostami, this artist addresses introspection issues in her works, sometimes more from reality in pieces such as Más allá del principio del placer (Beyond the Beginning of Pleasure), 2018, while other times she also does so from allegory as in Anoche soñé que volvía a Manderley (Last Night I Dreamt I Returned to Manderley), 2018 and Simbiosis (Symbiosis), 2018. In both examples the figures are blurred in the landscape, as if it were a memory or simply a film projection.

I do not cease to connect her entire work, but mainly Los pájaros (The Birds), 2018 or R, 2018, with the most experimental and paradoxical feature film of this exceptional filmmaker. Shirin is the film in which the camera captures the different emotions of 114 actresses when watching the projection of a love story. Their smiles, tears, and gestures are the only expressions that the director is interested in capturing with his lens. Just like this film, the author’s works are a tribute to privacy and a free way to remain in the painting alone with the emotions of the human being. Both in Kiarostami’s film and in Leticia’s oil paintings there is a background film that does not exist in reality beyond the soundtrack in the audiovisual and the references to moments we see in her paintings. As Kiarostami states, “The cinema is the art of showing by concealing. The spectator has to imagine, has to fill in the empty spaces, and has to have a creative attitude”.

Nevertheless, this artist’s creation excels the perception of a film scene, a fleeting and imperceptible moment for the human eye. Her painting is capable of reversing and transforming that fleetingness into a powerful existence, thus granting us a peaceful reading of those unstable but real emotions. For this reason, calling her a visual artist would not in the least be casual, regardless of the fact that the term has been employed to refer to those artists who stood out in the scene of plastic arts and originated new nomenclatures in art. In the case of Leticia, although she is attached to the classics from the visual arts point of view, she is capable of visualizing –in all the definitions of the term– and of materializing the essence of a melodrama.

In a postmodern society like ours, she is not interested in issues related to gender violence as we sometimes want to anchor female creators. Instead, she is concerned with neurosis, discouragement, loneliness and human alienation. Her vision is more existentialist and universal. From the point of view of the painting creation it is correct and valid to recognize the artist who succeeds in documenting a cinematographic content on a static visual plane and remarkably loaded with symbolism and emotions. The result of her work is a poetic creation that transmits this poetry. How does she achieve this? Perhaps from the most profound mental alienation.