Between Chaos and Familiar Strangeness

By Abram Bravo Guerra

My first glance at Gray Flesh, Geiler González’s series of collages/paintings, produced a kind of familiar strangeness. Strange at this point, there was something familiar that I was having trouble identifying, as if mountains of references I remembered visiting were piling up in the same quadrant. And I say strange because it has ceased to be usual not to be mathematically focused on what you see: there is too much crossed information, bombarded visualities, archetypes of creation that repeat themselves in a physical/cybernetic universe organized in not so casual searches. And, of course, part of an iconographic system, it is very clear in his proposal –we’ll get into it a little bit more–; the problem was that layer under the primary gaze, that one that seemed so clear and at the same time so disguised. Because if there is something that has captivated me in Geiler’s work, it is his unsettling capacity to always suggest something more, to make any analysis seem half-baked. There is a lot of morbidness in this, as if it were a kind of challenge, I have to admit that.

A few days ago we were talking and Geiler declared a kind of tripartite and equal interest: the fuel for this series was divided into a declared passion for anatomy, nature and the conscious revision of the History of Art. This scientific-artistic move struck me as clever although –perceptive, at last, on these subjects– I think I know that no one shows all their cards the first time around, there are even hidden hands that don’t come out in the open even if you want them to, as if they exist in an unconscious order arising only in the creative act. In other words, Gray Flesh is more interesting because of the system of elements that thread together the aforementioned tropes. Nonetheless, it is worthwhile to repair this initial idea.

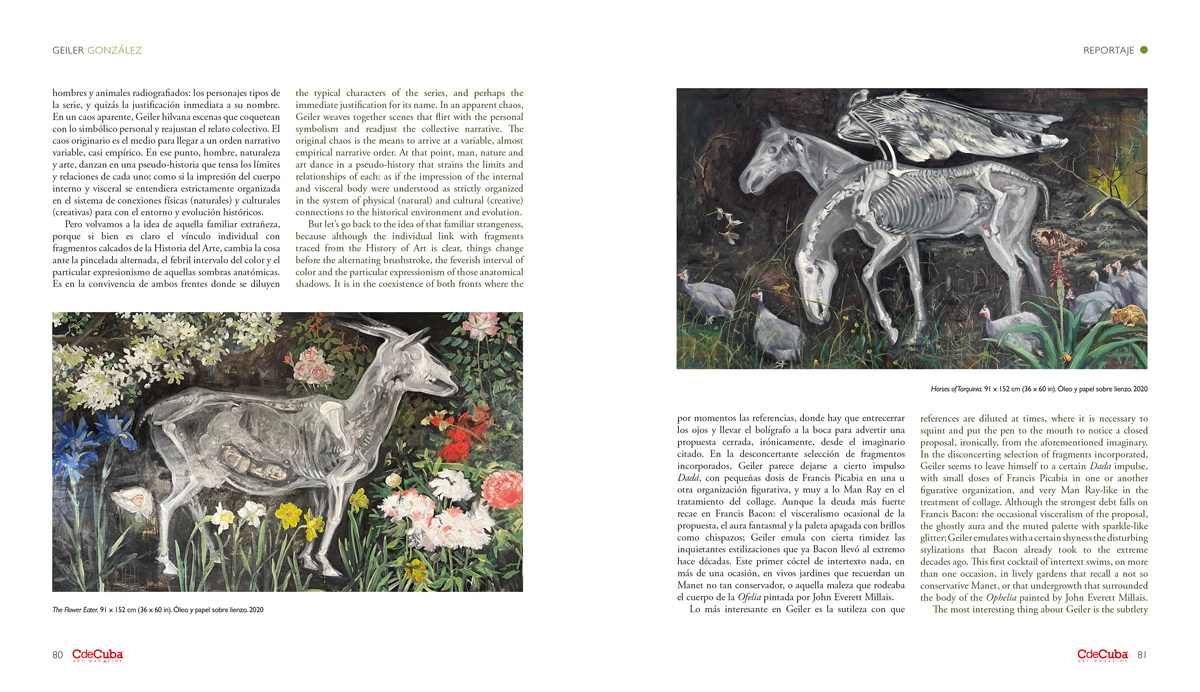

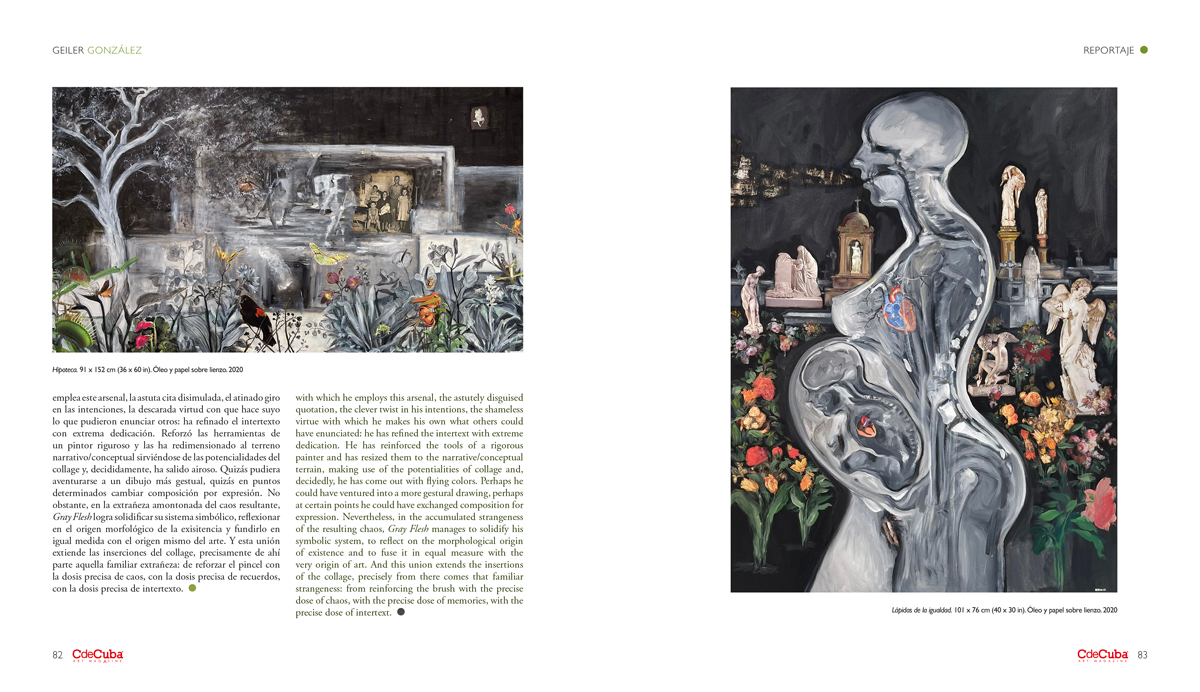

Gray Flesh is organized in independent scenes connected to each other, both technically and conceptually. They follow one another as reorganizations of the same operative body. In them, the artist uses both pure and hard painting and collage, taken from different supports: he pastes images of monuments, a scene by Velázquez, a character by Caravaggio, an angel by Cánova, a nymph by Ingres, a Spanish still life, a Greek Venus, an Egyptian statuette, etc. All this gravitates in natural environments, where the opaque greens turn to a dull gray and this, in turn, lights up in brief intervals of reddish or half-yellow flowers. Then, the glued figures and the careful natural background, coexist with radiographed men and animals: the typical characters of the series, and perhaps the immediate justification for its name. In an apparent chaos, Geiler weaves together scenes that flirt with the personal symbolism and readjust the collective narrative. The original chaos is the means to arrive at a variable, almost empirical narrative order. At that point, man, nature and art dance in a pseudo-history that strains the limits and relationships of each: as if the impression of the internal and visceral body were understood as strictly organized in the system of physical (natural) and cultural (creative) connections to the historical environment and evolution.

But let’s go back to the idea of that familiar strangeness, because although the individual link with fragments traced from the History of Art is clear, things change before the alternating brushstroke, the feverish interval of color and the particular expressionism of those anatomical shadows. It is in the coexistence of both fronts where the references are diluted at times, where it is necessary to squint and put the pen to the mouth to notice a closed proposal, ironically, from the aforementioned imaginary. In the disconcerting selection of fragments incorporated, Geiler seems to leave himself to a certain Dada impulse, with small doses of Francis Picabia in one or another figurative organization, and very Man Ray-like in the treatment of collage. Although the strongest debt falls on Francis Bacon: the occasional visceralism of the proposal, the ghostly aura and the muted palette with sparkle-like glitter; Geiler emulates with a certain shyness the disturbing stylizations that Bacon already took to the extreme decades ago. This first cocktail of intertext swims, on more than one occasion, in lively gardens that recall a not so conservative Manet, or that undergrowth that surrounded the body of the Ophelia painted by John Everett Millais.

The most interesting thing about Geiler is the subtlety with which he employs this arsenal, the astutely disguised quotation, the clever twist in his intentions, the shameless virtue with which he makes his own what others could have enunciated: he has refined the intertext with extreme dedication. He has reinforced the tools of a rigorous painter and has resized them to the narrative/conceptual terrain, making use of the potentialities of collage and, decidedly, he has come out with flying colors. Perhaps he could have ventured into a more gestural drawing, perhaps at certain points he could have exchanged composition for expression. Nevertheless, in the accumulated strangeness of the resulting chaos, Gray Flesh manages to solidify his symbolic system, to reflect on the morphological origin of existence and to fuse it in equal measure with the very origin of art. And this union extends the insertions of the collage, precisely from there comes that familiar strangeness: from reinforcing the brush with the precise dose of chaos, with the precise dose of memories, with the precise dose of intertext.