Of the Impossibility of Detaching Roots

By Mayvi Martiatu

The arrival of the avant-garde in Cuba, officially in 1927, meant in the artistic panorama, a negation of all the budgets and profits that had been established by the Academy. In spite of this, the first experiments of the modern avant-garde took place in academic genres such as landscape and portrait, placing some of its examples among the identifying works of the movement. Among them, the best known are Gitana tropical (Tropical Gypsy) by Víctor Manuel and Paisaje de La Habana (Havana landscape) by Rene Portocarrero.

In the case of landscapes, they soon became the platform for multiple pictorial experimentations, even abstract initiatives found inspiration in them and even titled their pieces with a clear allusion to them. The series Aguas territoriales (Territorial Waters) by Luis Martínez Pedro is one of the most obvious examples, although there are many others.

In Cuba, as in the rest of the countries, the arrival of postmodernism brought about the confluence of diverse movements and esthetics, as well as the return and enhancement of those manners and themes whose criticism had placed them in a specific period of the development of the arts. In the so-called New Cuban Art, pastiche, intertextuality and parody soon became part of the discursive tools of our creators. The representation of the Cuban reality was sifted by the constant presence of these actors, which undoubtedly enriched the artistic trope and made it more complex in that process of multiple metaphorical performances.

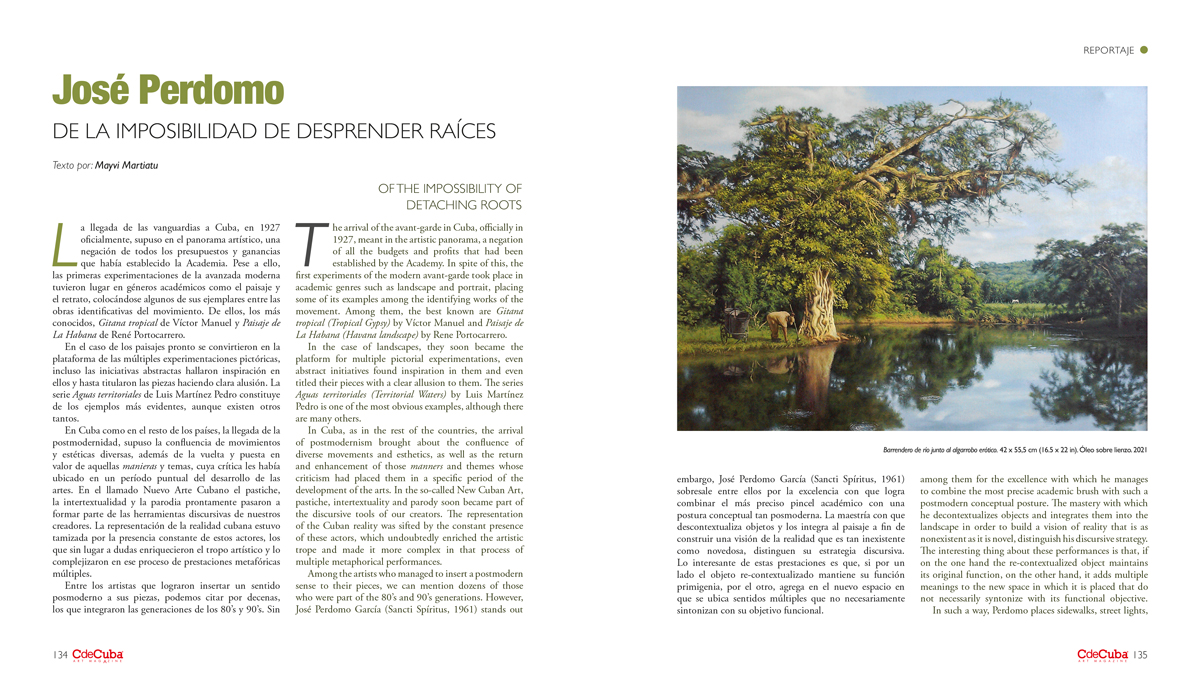

Among the artists who managed to insert a postmodern sense to their pieces, we can mention dozens of those who were part of the 80’s and 90’s generations. However, José Perdomo García (Sancti Spíritus, 1961) stands out among them for the excellence with which he manages to combine the most precise academic brush with such a postmodern conceptual posture. The mastery with which he decontextualizes objects and integrates them into the landscape in order to build a vision of reality that is as nonexistent as it is novel, distinguish his discursive strategy. The interesting thing about these performances is that, if on the one hand the re-contextualized object maintains its original function, on the other hand, it adds multiple meanings to the new space in which it is placed that do not necessarily syntonize with its functional objective.

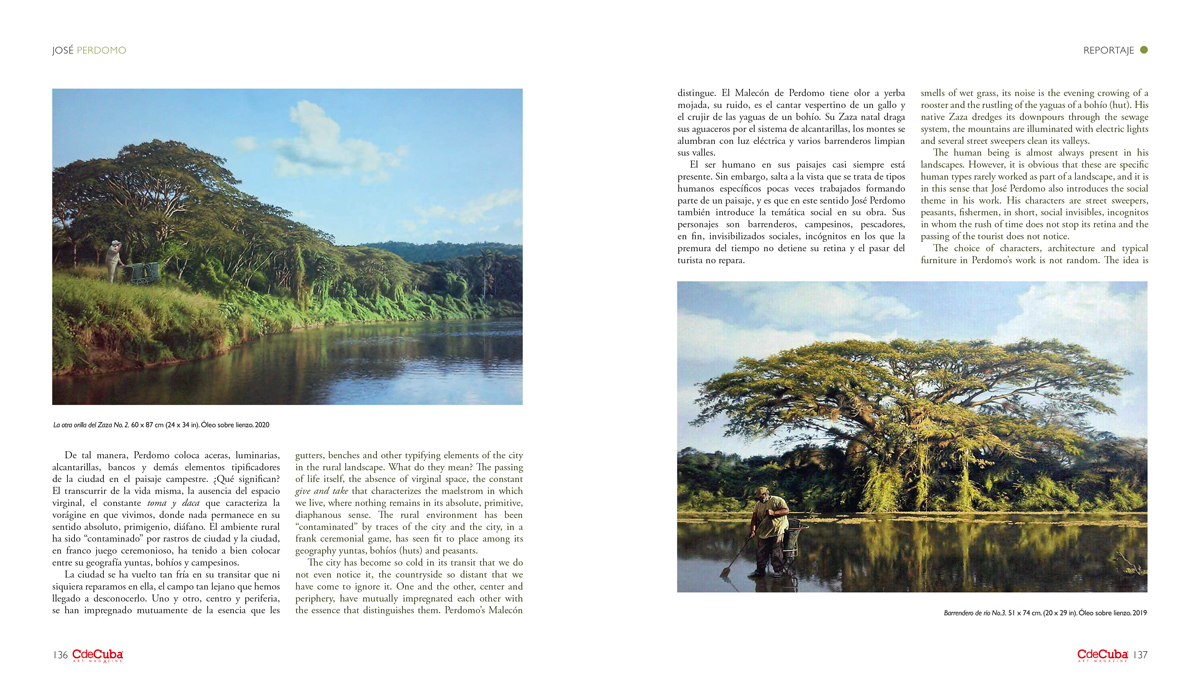

In such a way, Perdomo places sidewalks, street lights, gutters, benches and other typifying elements of the city in the rural landscape. What do they mean? The passing of life itself, the absence of virginal space, the constant give and take that characterizes the maelstrom in which we live, where nothing remains in its absolute, primitive, diaphanous sense. The rural environment has been “contaminated” by traces of the city and the city, in a frank ceremonial game, has seen fit to place among its geography yuntas, bohíos (huts) and peasants.

The city has become so cold in its transit that we do not even notice it, the countryside so distant that we have come to ignore it. One and the other, center and periphery, have mutually impregnated each other with the essence that distinguishes them. Perdomo’s Malecón smells of wet grass, its noise is the evening crowing of a rooster and the rustling of the yaguas of a bohío (hut). His native Zaza dredges its downpours through the sewage system, the mountains are illuminated with electric lights and several street sweepers clean its valleys.

The human being is almost always present in his landscapes. However, it is obvious that these are specific human types rarely worked as part of a landscape, and it is in this sense that José Perdomo also introduces the social theme in his work. His characters are street sweepers, peasants, fishermen, in short, social invisibles, incognitos in whom the rush of time does not stop its retina and the passing of the tourist does not notice.

The choice of characters, architecture and typical furniture in Perdomo’s work is not random. The idea is to elevate to the category of protagonist that which goes unnoticed in the daily passing through these environments, to place the spotlight there and make them noticeable from their dissonant location.

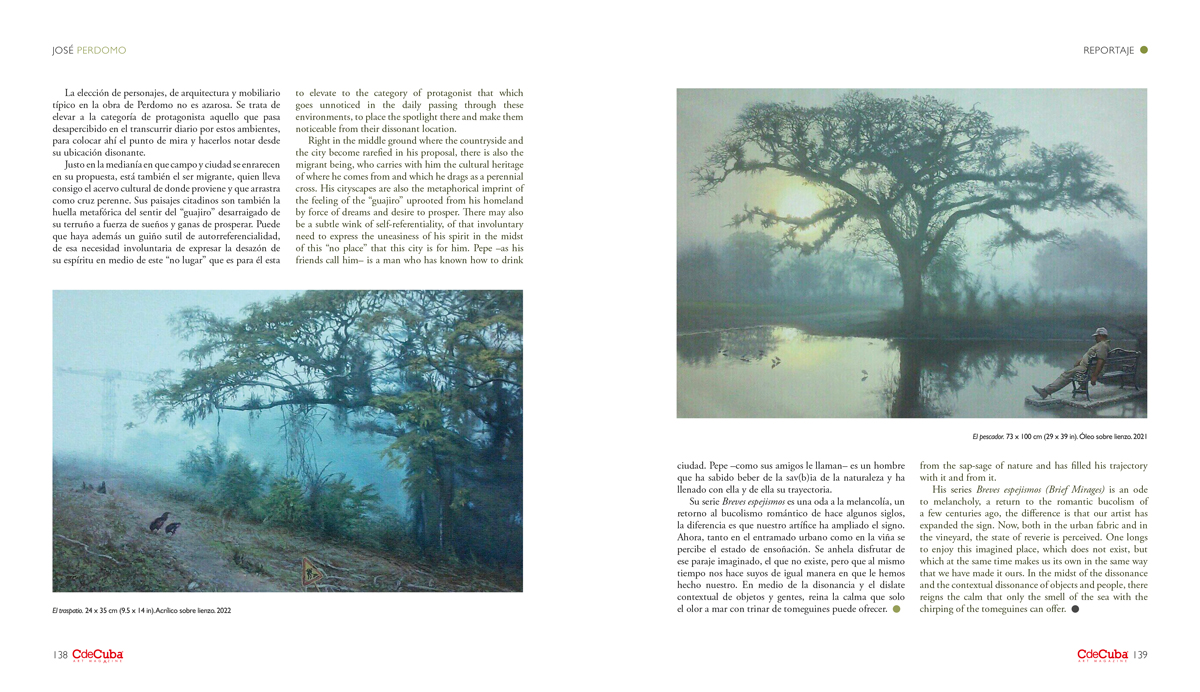

Right in the middle ground where the countryside and the city become rarefied in his proposal, there is also the migrant being, who carries with him the cultural heritage of where he comes from and which he drags as a perennial cross. His cityscapes are also the metaphorical imprint of the feeling of the “guajiro” uprooted from his homeland by force of dreams and desire to prosper. There may also be a subtle wink of self-referentiality, of that involuntary need to express the uneasiness of his spirit in the midst of this “no place” that this city is for him. Pepe –as his friends call him– is a man who has known how to drink from the sap-sage of nature and has filled his trajectory with it and from it.

His series Breves espejismos (Brief Mirages) is an ode to melancholy, a return to the romantic bucolism of a few centuries ago, the difference is that our artist has expanded the sign. Now, both in the urban fabric and in the vineyard, the state of reverie is perceived. One longs to enjoy this imagined place, which does not exist, but which at the same time makes us its own in the same way that we have made it ours. In the midst of the dissonance and the contextual dissonance of objects and people, there reigns the calm that only the smell of the sea with the chirping of the tomeguines can offer.