Sumptuous Abandoned Palaces

By Antonio Correa Iglesias

Imet Julio Figueroa Beltrán in 2004 when he was beginning his studies in the Faculty of Fine Arts at the Higher Institute of Art in Havana. That was a “distinct and different” year, I remember that I always gave my philosophy classes –nothing Marxist– in the cafeteria, in the shade of huge framboyant trees that, in complicity with a persistent breeze, made all those students fall exhausted not perhaps by my arguments, but by the long heat that was fermenting in their stomachs of rice, peas and eggs. I must also say that one fine day Julio disappeared and only sixteen years later he appeared at the Kendall Art Center in Miami. José Lezama Lima called this –and rightly so– “concurrent chance”. With you in the distance, distance has that, it allows us to see things from another perspective.

When Julio Figueroa Beltrán invited me to review his painting, I was faced with at least three fundamental dilemmas:

- Can art be judged in an appropriate or inappropriate way?

- What is and who judges what is appropriate and inappropriate in terms of art?

- If in order to make a judgment about contemporary art it is necessary to have a deep knowledge of the history of art, is this not fostering a kind of “emotional blindness1” in its consumption?

This text is based on these three dilemmas, without implying, in its development, that we have to find answers.

One of the distinctions on the basis of which the entire historiography of Western art has been established is the tension-distension between the “beautiful” and the “non-beautiful”. Based on these two elements, a narrative has been constructed that places on one side or the other –in an exclusive manner– a determined and determining production of works of art. This element, historicized by Umberto Eco, acquires in Julio Figueroa Beltrán’s work a character that is not only contemporary but also sui generis.

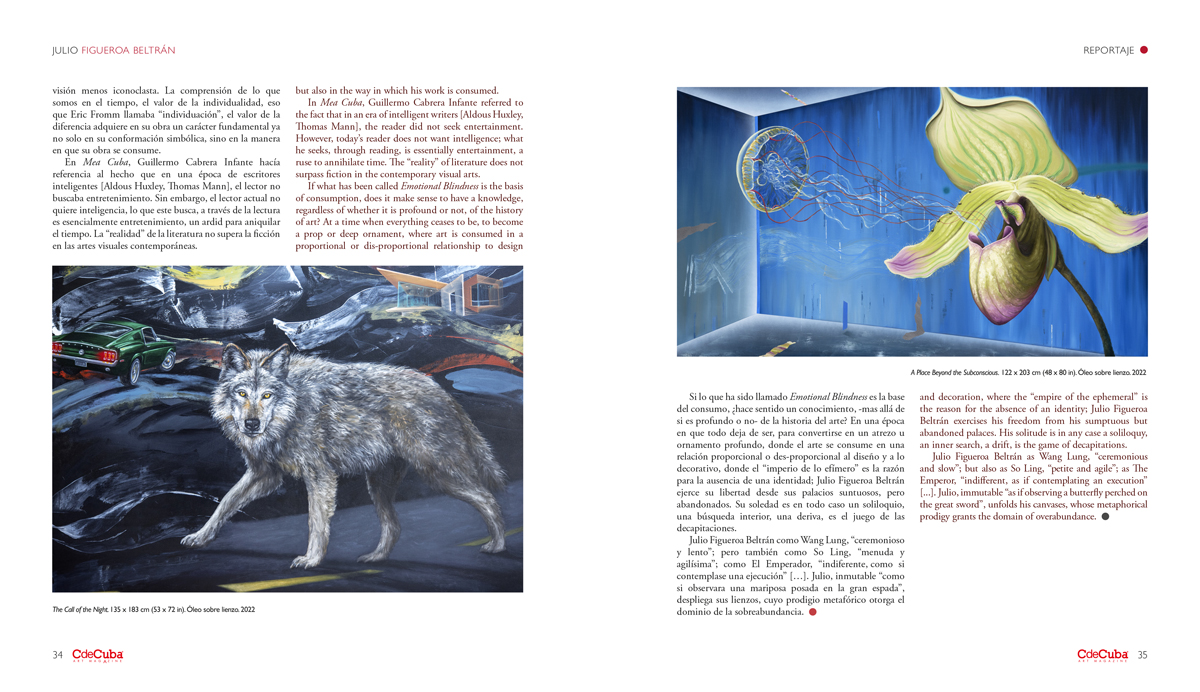

His painting takes place in these two apparently unconnected dimensions. If the works that deal with non-places –which in this analogy would be the “grotesque”– occupy an important place and capture the center of attention, there is a whole “landscape” production that is somewhat “bucolic” that complements it. In any case, these two spheres are connected by the “intrusion” of territory into space, generating a sort of return or recovery of freedom.

In either case, a haven of deep hedonism articulates a visuality that at intervals gives the impression of an ubiquity of the immediate. Being here and now and everywhere, places the subject of his painting in the disjunctive of his existence. The contradictions, –of present body– make Julio’s painting a sort of delirium tremens that torments those who, fascinated, try to establish a logical or teleological connection in the face of a strangeness that is reluctant to confluence.

But it is precisely from these tensions that an intimate sense emerges that overflows in a visuality that knows how to produce a symbolic balance in the composition. There is a search for the peaceful, for what emotionally engages us, –that which in English is called the “self” that goes beyond the “I”– as opposed to a mundane effort to empty our existence of content.

On the other hand, Julio Figueroa Beltrán’s painting takes place out of time, or at least it does not take place in the linear time trapped in clocks. His creatures gravitate, they are evocations of the senses, apparitions, specters, critical consciences that invert anguish and anxiety to liquefy, in an intellectual exercise, the search for visual pleasure. Pleasure, always so elusive in contemporary art.

Julio “plays” with ataraxia as a means of freeing the soul from identification or dependence on the body in order to merge into a mystical space. This is precisely the sensation provoked by his pictorial work, a work that debates from two strictly nominal spaces.

To the dense affliction, as an expression of the absurd, of what we have called non-places, Julio interposes a less iconoclastic vision. The understanding of what we are in time, the value of individuality, what Eric Fromm called “individuation”, the value of difference acquires in his work a fundamental character not only in its symbolic conformation, but also in the way in which his work is consumed.

In Mea Cuba, Guillermo Cabrera Infante referred to the fact that in an era of intelligent writers [Aldous Huxley, Thomas Mann], the reader did not seek entertainment. However, today’s reader does not want intelligence; what he seeks, through reading, is essentially entertainment, a ruse to annihilate time. The “reality” of literature does not surpass fiction in the contemporary visual arts.

If what has been called Emotional Blindness is the basis of consumption, does it make sense to have a knowledge, regardless of whether it is profound or not, of the history of art? At a time when everything ceases to be, to become a prop or deep ornament, where art is consumed in a proportional or dis-proportional relationship to design and decoration, where the “empire of the ephemeral” is the reason for the absence of an identity; Julio Figueroa Beltrán exercises his freedom from his sumptuous but abandoned palaces. His solitude is in any case a soliloquy, an inner search, a drift, is the game of decapitations.

Julio Figueroa Beltrán as Wang Lung, “ceremonious and slow”; but also as So Ling, “petite and agile”; as The Emperor, “indifferent, as if contemplating an execution” […]. Julio, immutable “as if observing a butterfly perched on the great sword”, unfolds his canvases, whose metaphorical prodigy grants the domain of overabundance.

For Ben-Ami Scharfstein “emotional blindness, found in varying degrees among the selfisf, the narcissistic, and the autistic sociate” Page 79 “The nonsense of Kant and Lewis Carrol” The University of Chicago Press 2014