Eros and Thanatos: The Sad Beauty of Reality

By Liannys Lisset Peña Rodríguez

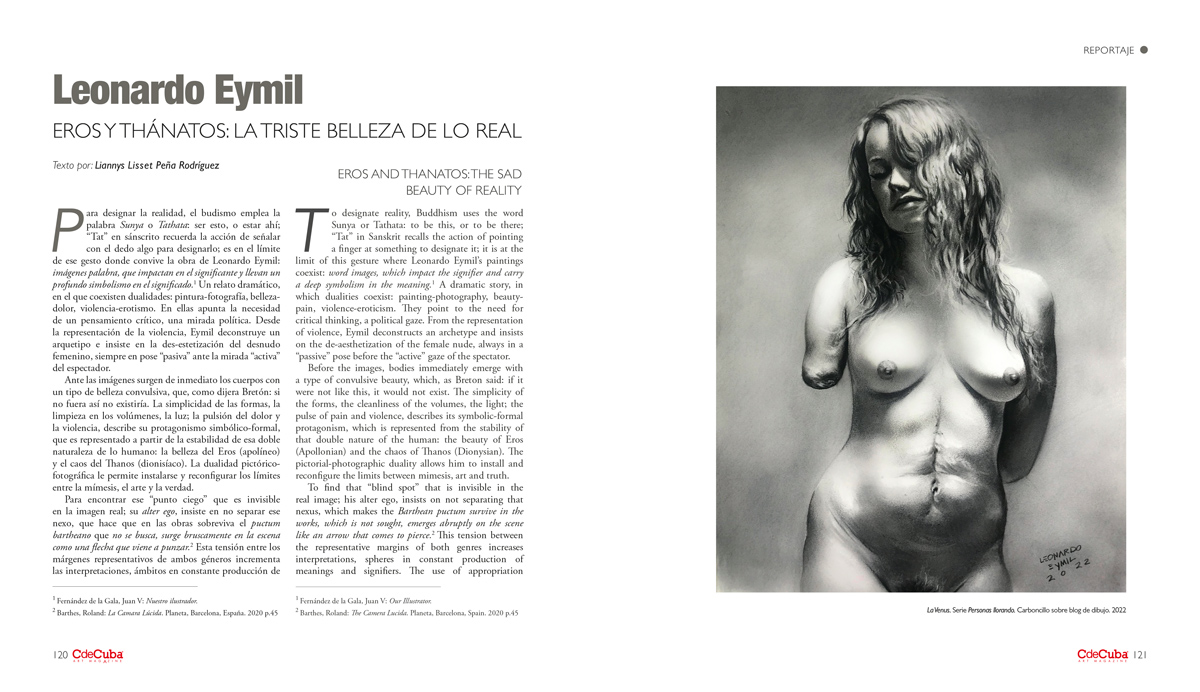

To designate reality, Buddhism uses the word Sunya or Tathata: to be this, or to be there; “Tat” in Sanskrit recalls the action of pointing a finger at something to designate it; it is at the limit of this gesture where Leonardo Eymil’s paintings coexist: word images, which impact the signifier and carry a deep symbolism in the meaning.1 A dramatic story, in which dualities coexist: painting-photography, beauty-pain, violence-eroticism. They point to the need for critical thinking, a political gaze. From the representation of violence, Eymil deconstructs an archetype and insists on the de-aesthetization of the female nude, always in a “passive” pose before the “active” gaze of the spectator.

Before the images, bodies immediately emerge with a type of convulsive beauty, which, as Breton said: if it were not like this, it would not exist. The simplicity of the forms, the cleanliness of the volumes, the light; the pulse of pain and violence, describes its symbolic-formal protagonism, which is represented from the stability of that double nature of the human: the beauty of Eros (Apollonian) and the chaos of Thanos (Dionysian). The pictorial-photographic duality allows him to install and reconfigure the limits between mimesis, art and truth.

To find that “blind spot” that is invisible in the real image; his alter ego, insists on not separating that nexus, which makes the Barthean puctum survive in the works, which is not sought, emerges abruptly on the scene like an arrow that comes to pierce.2 This tension between the representative margins of both genres increases interpretations, spheres in constant production of meanings and signifiers. The use of appropriation techniques, the liberation of referents, and the constructive activity of symbols makes the pictorial emerge as “the image of the image”, hybrid, segmented, in a history of stories where a reordering of imaginative materials is produced to provide them with an “other” meaning. The backgrounds are plain, simple, the weight falls on the figure, in the foreground, and extension of the pictorial frame; accompanied by elements of symbolic support, they are treated with chromatic-structural richness. Eymil insists on the trace of the brush or charcoal on the canvas, some accidental impasto to the realistic impulse, solutions, glazes; in an intentional construction of the artifice and effectiveness of the real. To surpass the mimetic effect and make beauty explode and be totally visible, he proposes the use of a hybrid trompe-l’oeil, contemporary distortions, pixelated, (dis)framing, (dis)assemblies.

Venus is one of those images, dark as hieroglyphics, with which according to Didi-Huberman one must take distance, to read them, decompose them, trace them, certainly in her there is a kind of symbolic connotation; an allegory to the prehistoric and Hellenistic Greek statuary; the paradoxical rawness between the real (scars, wrinkles, folds) and the symbolic value associated with the original referents (sexist connotation of the mythical archetype) is contrasted. The artist manipulates the figure achieving a kind of contemporary nuance; he makes the skin a symbolic surface; a redoubt, which takes us through the memory of bodies: support, envelope, intermediary between itself and the other.

Eymil is perhaps that type of Baudelairean painter who insists on pain and pleasure as detonators of that disturbing sense and limit of experience; that painter that a mocking god forces to paint over the darkness;3 to do so he has created a cosmos that he translates through bodies, faces, gestures, languages.

Sad Virgin is a work that, from its beautiful face, interrogates us, hides the “I”, which remains fragile but exposes the lacerations, the blood. Dino Vals said that (…) they usually look into the eyes of the painter because they are self-portraits, and of the spectator because they are mirrors (…)

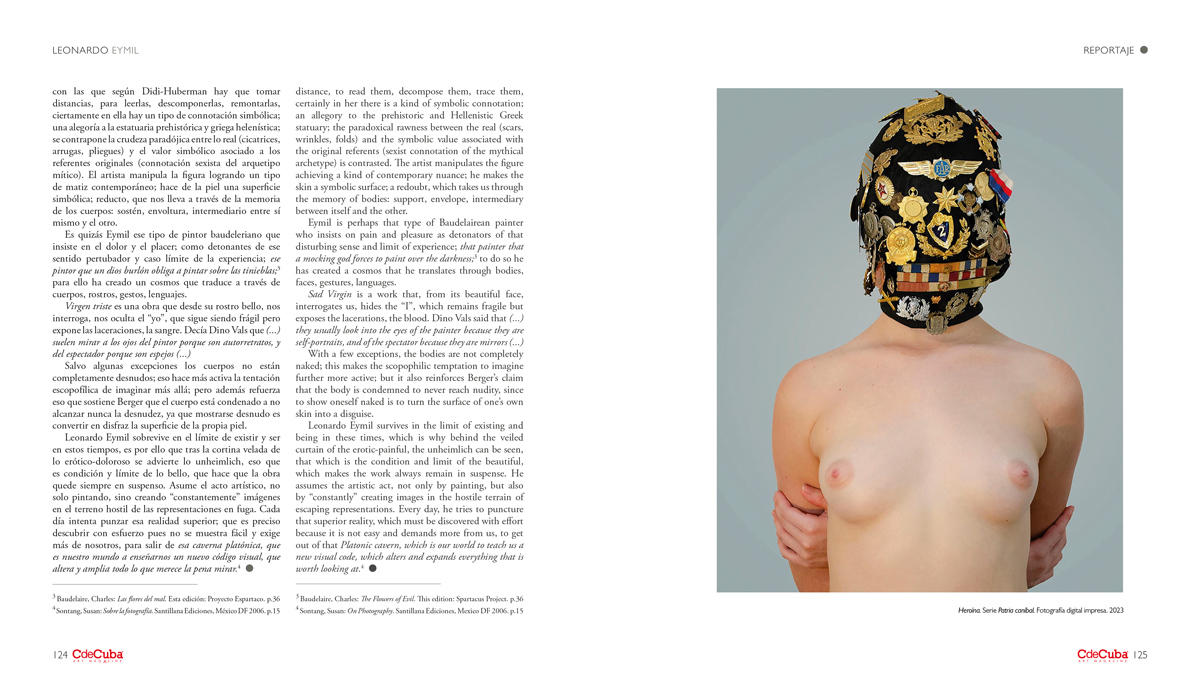

With a few exceptions, the bodies are not completely naked; this makes the scopophilic temptation to imagine further more active; but it also reinforces Berger’s claim that the body is condemned to never reach nudity, since to show oneself naked is to turn the surface of one’s own skin into a disguise.

Leonardo Eymil survives in the limit of existing and being in these times, which is why behind the veiled curtain of the erotic-painful, the unheimlich can be seen, that which is the condition and limit of the beautiful, which makes the work always remain in suspense. He assumes the artistic act, not only by painting, but also by “constantly” creating images in the hostile terrain of escaping representations. Every day, he tries to puncture that superior reality, which must be discovered with effort because it is not easy and demands more from us, to get out of that Platonic cavern, which is our world to teach us a new visual code, which alters and expands everything that is worth looking at.4

1 Fernández de la Gala, Juan V: Our Illustrator.

2 Barthes, Roland: The Camera Lucida. Planeta, Barcelona, Spain. 2020 p.45

3 Baudelaire, Charles: The Flowers of Evil. This edition: Spartacus Project. p.36

4 Sontang, Susan: On Photography. Santillana Ediciones, Mexico DF 2006. p.15