An Inner Light

By Rigoberto Almaguer

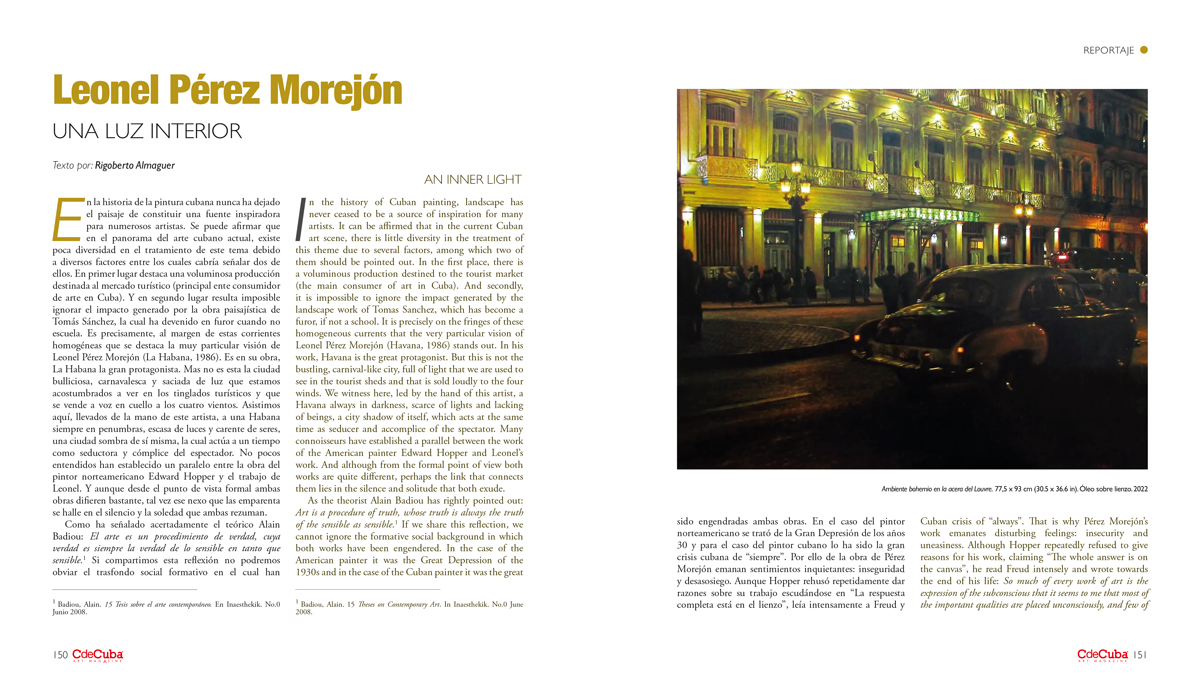

In the history of Cuban painting, landscape has never ceased to be a source of inspiration for many artists. It can be affirmed that in the current Cuban art scene, there is little diversity in the treatment of this theme due to several factors, among which two of them should be pointed out. In the first place, there is a voluminous production destined to the tourist market (the main consumer of art in Cuba). And secondly, it is impossible to ignore the impact generated by the landscape work of Tomas Sanchez, which has become a furor, if not a school. It is precisely on the fringes of these homogeneous currents that the very particular vision of Leonel Pérez Morejón (Havana, 1986) stands out. In his work, Havana is the great protagonist. But this is not the bustling, carnival-like city, full of light that we are used to see in the tourist sheds and that is sold loudly to the four winds. We witness here, led by the hand of this artist, a Havana always in darkness, scarce of lights and lacking of beings, a city shadow of itself, which acts at the same time as seducer and accomplice of the spectator. Many connoisseurs have established a parallel between the work of the American painter Edward Hopper and Leonel’s work. And although from the formal point of view both works are quite different, perhaps the link that connects them lies in the silence and solitude that both exude.

As the theorist Alain Badiou has rightly pointed out: Art is a procedure of truth, whose truth is always the truth of the sensible as sensible.1 If we share this reflection, we cannot ignore the formative social background in which both works have been engendered. In the case of the American painter it was the Great Depression of the 1930s and in the case of the Cuban painter it was the great Cuban crisis of “always”. That is why Pérez Morejón’s work emanates disturbing feelings: insecurity and uneasiness. Although Hopper repeatedly refused to give reasons for his work, claiming “The whole answer is on the canvas”, he read Freud intensely and wrote towards the end of his life: So much of every work of art is the expression of the subconscious that it seems to me that most of the important qualities are placed unconsciously, and few of importance by the conscious intellect.2

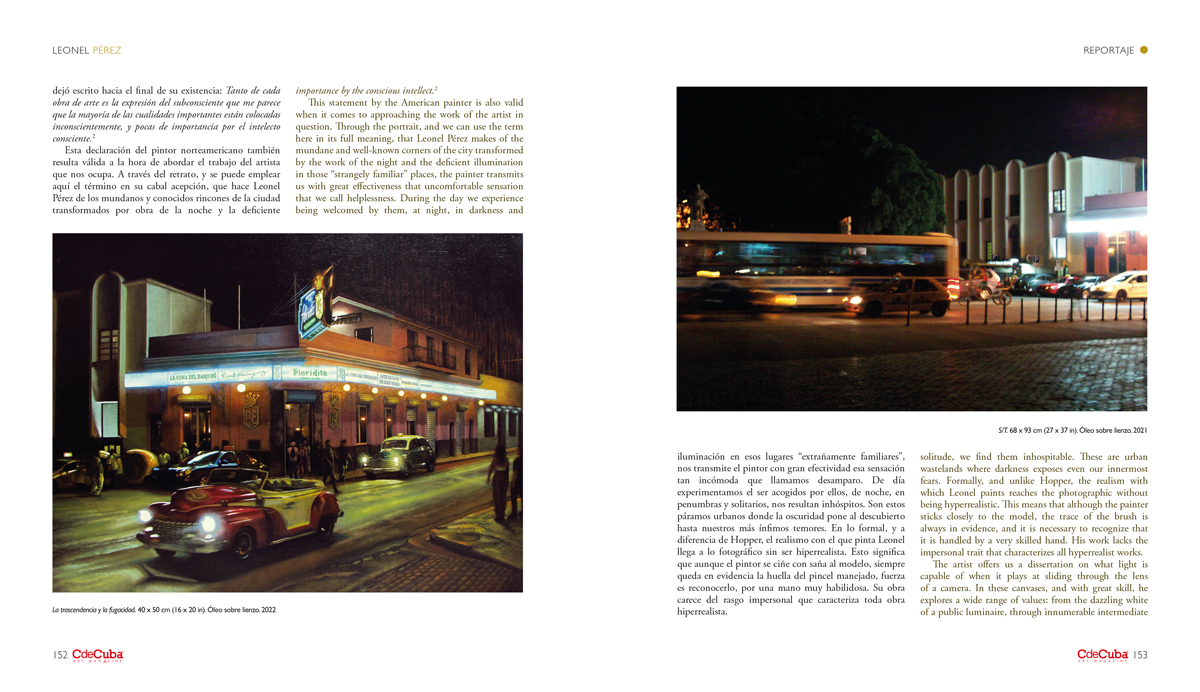

This statement by the American painter is also valid when it comes to approaching the work of the artist in question. Through the portrait, and we can use the term here in its full meaning, that Leonel Pérez makes of the mundane and well-known corners of the city transformed by the work of the night and the deficient illumination in those “strangely familiar” places, the painter transmits us with great effectiveness that uncomfortable sensation that we call helplessness. During the day we experience being welcomed by them, at night, in darkness and solitude, we find them inhospitable. These are urban wastelands where darkness exposes even our innermost fears. Formally, and unlike Hopper, the realism with which Leonel paints reaches the photographic without being hyperrealistic. This means that although the painter sticks closely to the model, the trace of the brush is always in evidence, and it is necessary to recognize that it is handled by a very skilled hand. His work lacks the impersonal trait that characterizes all hyperrealist works.

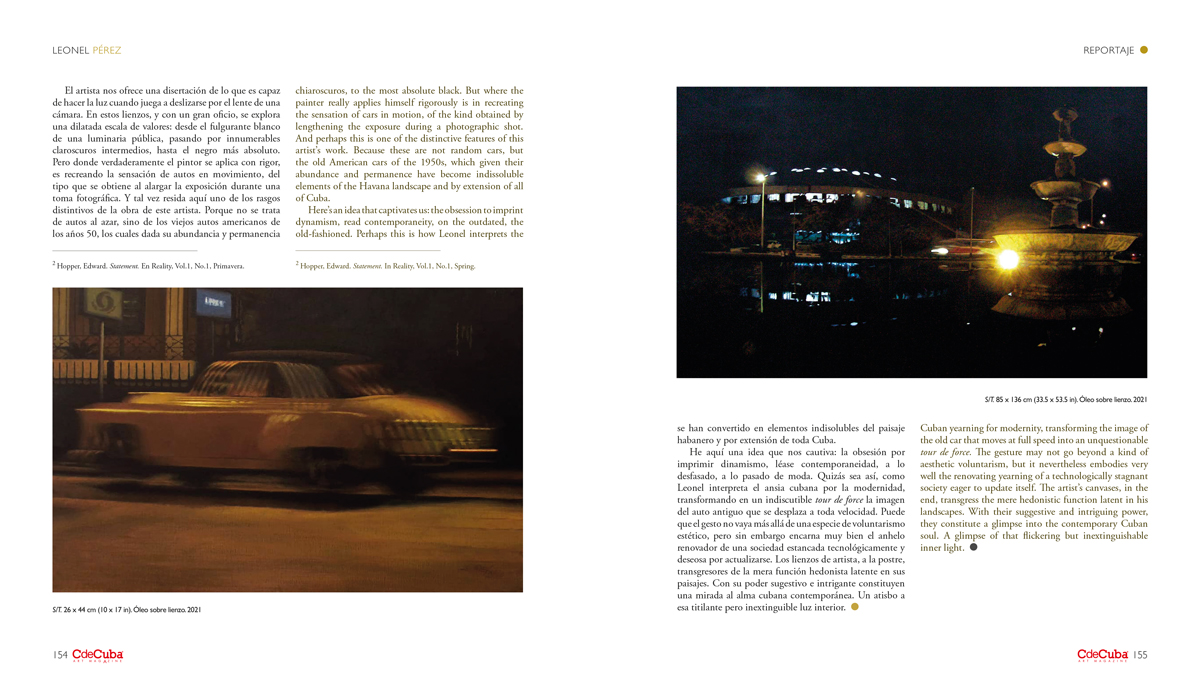

The artist offers us a dissertation on what light is capable of when it plays at sliding through the lens of a camera. In these canvases, and with great skill, he explores a wide range of values: from the dazzling white of a public luminaire, through innumerable intermediate chiaroscuros, to the most absolute black. But where the painter really applies himself rigorously is in recreating the sensation of cars in motion, of the kind obtained by lengthening the exposure during a photographic shot. And perhaps this is one of the distinctive features of this artist’s work. Because these are not random cars, but the old American cars of the 1950s, which given their abundance and permanence have become indissoluble elements of the Havana landscape and by extension of all of Cuba.

Here’s an idea that captivates us: the obsession to imprint dynamism, read contemporaneity, on the outdated, the old-fashioned. Perhaps this is how Leonel interprets the Cuban yearning for modernity, transforming the image of the old car that moves at full speed into an unquestionable tour de force. The gesture may not go beyond a kind of aesthetic voluntarism, but it nevertheless embodies very well the renovating yearning of a technologically stagnant society eager to update itself. The artist’s canvases, in the end, transgress the mere hedonistic function latent in his landscapes. With their suggestive and intriguing power, they constitute a glimpse into the contemporary Cuban soul. A glimpse of that flickering but inextinguishable inner light.

Badiou, Alain. 15 Theses on Contemporary Art. In Inaesthekik. No.0 June 2008.

Hopper, Edward. Statement. In Reality, Vol.1, No.1, Spring.