Servant’s Atonement

By Rufo Caballero

The art criticism that prevailed in the eighties was not capable of noticing the magnitude of a painter like Ruben Rodríguez. That was a very eruptive moment, and the poetics that were on the crest of the wave had, sought, the seal of rupture, of the passion with which they opposed anything (power, criticism, the rest of art, institutions; anything). Ruben’s impetus, however, was elsewhere: it was the courage of independence, the strength of autonomy. At a time when everyone was making questioning art, Rubén decided to face the greatest rebelliousness of all: that which raises his own work above the temptations of contingency, and proposes to consolidate the quality of painting itself, with absolute disdain for the prevailing coordinates of the time.

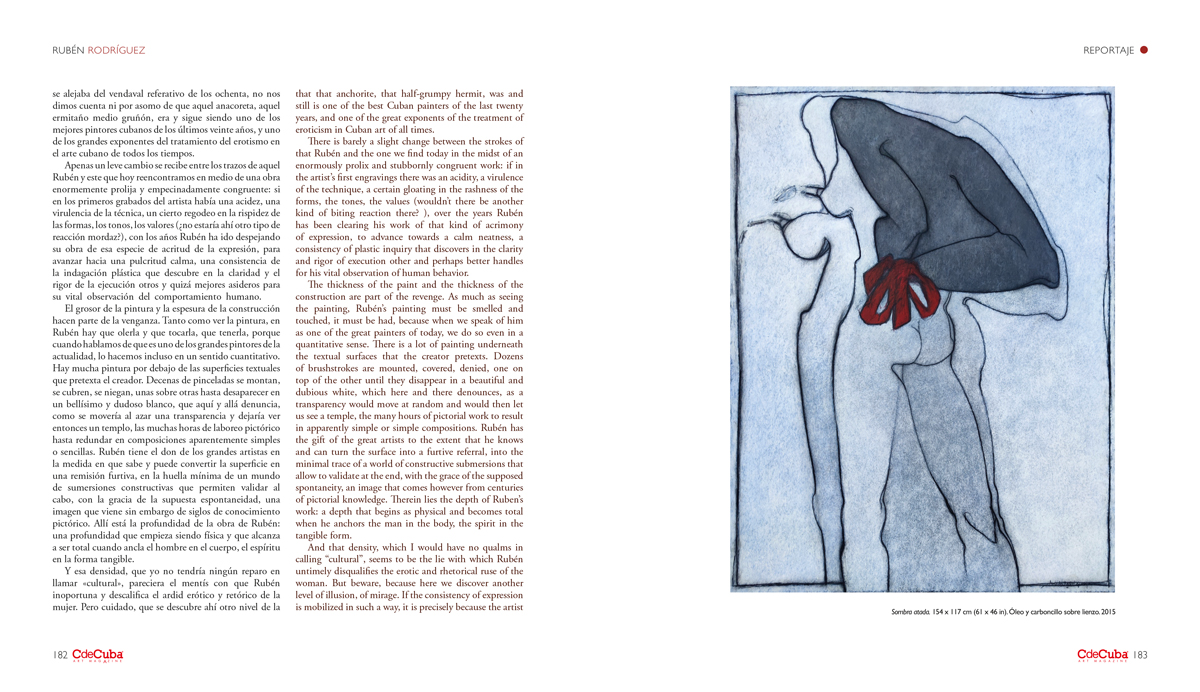

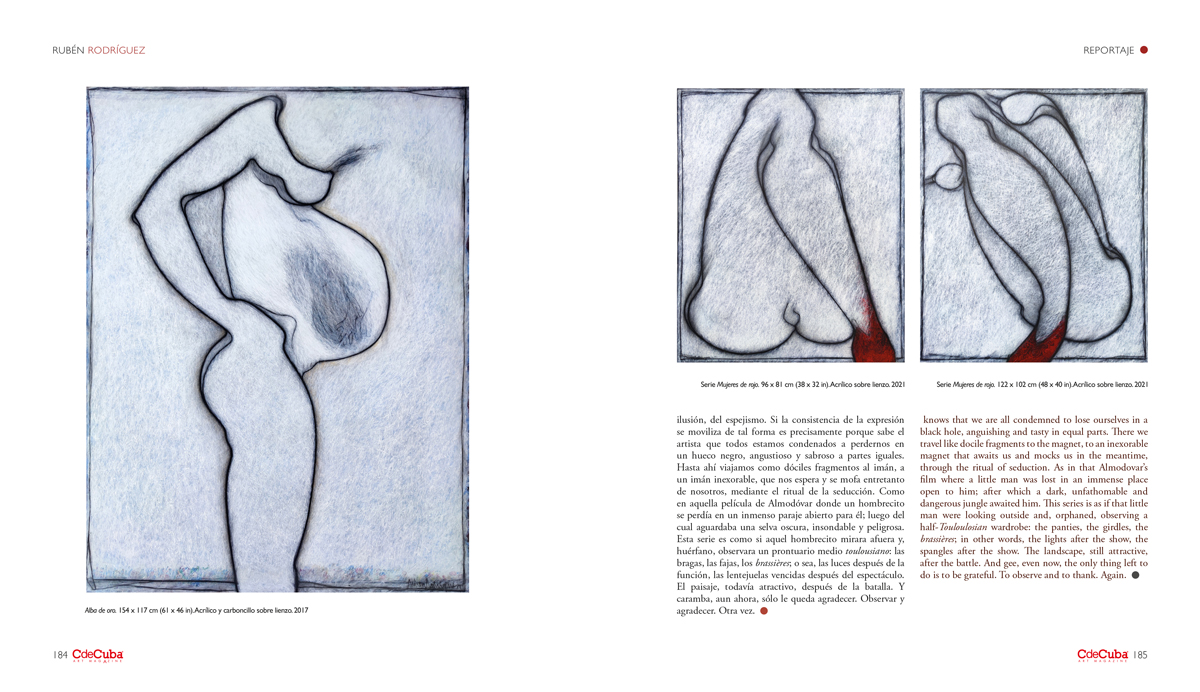

Rubén made of the human body a cathedral, a semantic device that, even if eventually loaded with certain meditations of another scope (the relationship between popular culture, religiosity and erotic expression in the nature of the Cuban, for example), has dealt mostly with the human condition, expressed and imprisoned in its physical indexes. More than anything else, the woman’s body represents the seat of a sharp power of observation that speculates on the sweet twists of desire, possession, the thirst of erotic dependence, the unwillingness of abandonment, the withdrawal of the feeling that confesses itself in the marks of the body.

Rubén’s fiercely personal figuration could be inscribed in an artistic sensibility that oscillates between the codes of the “new figuration” and neo-expressionism, but it cannot be associated with any one of the international cultivators of that tradition. At the most, in Rubén one can perceive an air of the times, a very contemporary sensibility at the time of cutting out the figures on the perspective of the city, the world, or “reality”, notions that for the artist are neutralities equivalent to emptiness, to absence. Rubén belongs to that lineage of painters who founded a figuration, without allowing the value of the new repertoire to reside in the description of the world. Rather, the value of these imaginaries lies in their own artistic strength, in the rational impossibility of explaining the secret process of their construction. It is in this sense that I say that, although we were always captivated by the verticality with which that boy of the eighties, with the appearance of an insular bear between the aggressiveness and tenderness of his introspection, exposed to the four winds a densely erotic work that, without being “intimate”, was far from the referative gale of the eighties, we did not even realize that that anchorite, that half-grumpy hermit, was and still is one of the best Cuban painters of the last twenty years, and one of the great exponents of the treatment of eroticism in Cuban art of all times.

There is barely a slight change between the strokes of that Rubén and the one we find today in the midst of an enormously prolix and stubbornly congruent work: if in the artist’s first engravings there was an acidity, a virulence of the technique, a certain gloating in the rashness of the forms, the tones, the values (wouldn’t there be another kind of biting reaction there? ), over the years Rubén has been clearing his work of that kind of acrimony of expression, to advance towards a calm neatness, a consistency of plastic inquiry that discovers in the clarity and rigor of execution other and perhaps better handles for his vital observation of human behavior.

The thickness of the paint and the thickness of the construction are part of the revenge. As much as seeing the painting, Rubén’s painting must be smelled and touched, it must be had, because when we speak of him as one of the great painters of today, we do so even in a quantitative sense. There is a lot of painting underneath the textual surfaces that the creator pretexts. Dozens of brushstrokes are mounted, covered, denied, one on top of the other until they disappear in a beautiful and dubious white, which here and there denounces, as a transparency would move at random and would then let us see a temple, the many hours of pictorial work to result in apparently simple or simple compositions. Rubén has the gift of the great artists to the extent that he knows and can turn the surface into a furtive referral, into the minimal trace of a world of constructive submersions that allow to validate at the end, with the grace of the supposed spontaneity, an image that comes however from centuries of pictorial knowledge. Therein lies the depth of Ruben’s work: a depth that begins as physical and becomes total when he anchors the man in the body, the spirit in the tangible form.

And that density, which I would have no qualms in calling “cultural”, seems to be the lie with which Rubén untimely disqualifies the erotic and rhetorical ruse of the woman. But beware, because here we discover another level of illusion, of mirage. If the consistency of expression is mobilized in such a way, it is precisely because the artist knows that we are all condemned to lose ourselves in a black hole, anguishing and tasty in equal parts. There we travel like docile fragments to the magnet, to an inexorable magnet that awaits us and mocks us in the meantime, through the ritual of seduction. As in that Almodovar’s film where a little man was lost in an immense place open to him; after which a dark, unfathomable and dangerous jungle awaited him. This series is as if that little man were looking outside and, orphaned, observing a half-Touloulosian wardrobe: the panties, the girdles, the brassières; in other words, the lights after the show, the spangles after the show. The landscape, still attractive, after the battle. And gee, even now, the only thing left to do is to be grateful. To observe and to thank. Again.