The Body’s Selfish Narrative

By Abram Bravo Guerra

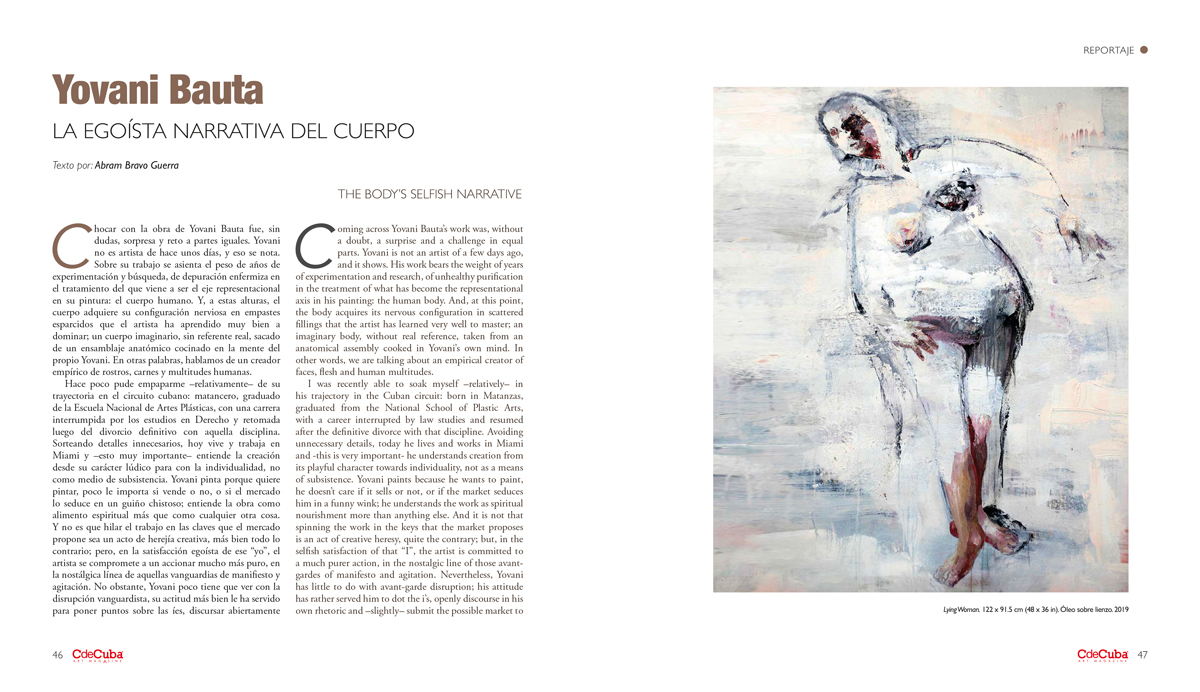

Coming across Yovani Bauta’s work was, without a doubt, a surprise and a challenge in equal parts. Yovani is not an artist of a few days ago, and it shows. His work bears the weight of years of experimentation and research, of unhealthy purification in the treatment of what has become the representational axis in his painting: the human body. And, at this point, the body acquires its nervous configuration in scattered fillings that the artist has learned very well to master; an imaginary body, without real reference, taken from an anatomical assembly cooked in Yovani’s own mind. In other words, we are talking about an empirical creator of faces, flesh and human multitudes.

I was recently able to soak myself –relatively– in his trajectory in the Cuban circuit: born in Matanzas, graduated from the National School of Plastic Arts, with a career interrupted by law studies and resumed after the definitive divorce with that discipline. Avoiding unnecessary details, today he lives and works in Miami and -this is very important- he understands creation from its playful character towards individuality, not as a means of subsistence. Yovani paints because he wants to paint, he doesn’t care if it sells or not, or if the market seduces him in a funny wink; he understands the work as spiritual nourishment more than anything else. And it is not that spinning the work in the keys that the market proposes is an act of creative heresy, quite the contrary; but, in the selfish satisfaction of that “I”, the artist is committed to a much purer action, in the nostalgic line of those avant-gardes of manifesto and agitation. Nevertheless, Yovani has little to do with avant-garde disruption; his attitude has rather served him to dot the i’s, openly discourse in his own rhetoric and –slightly– submit the possible market to his interest. Like those 20th century nomads who, by dint of tooth and nail, made the personal a collective brand.

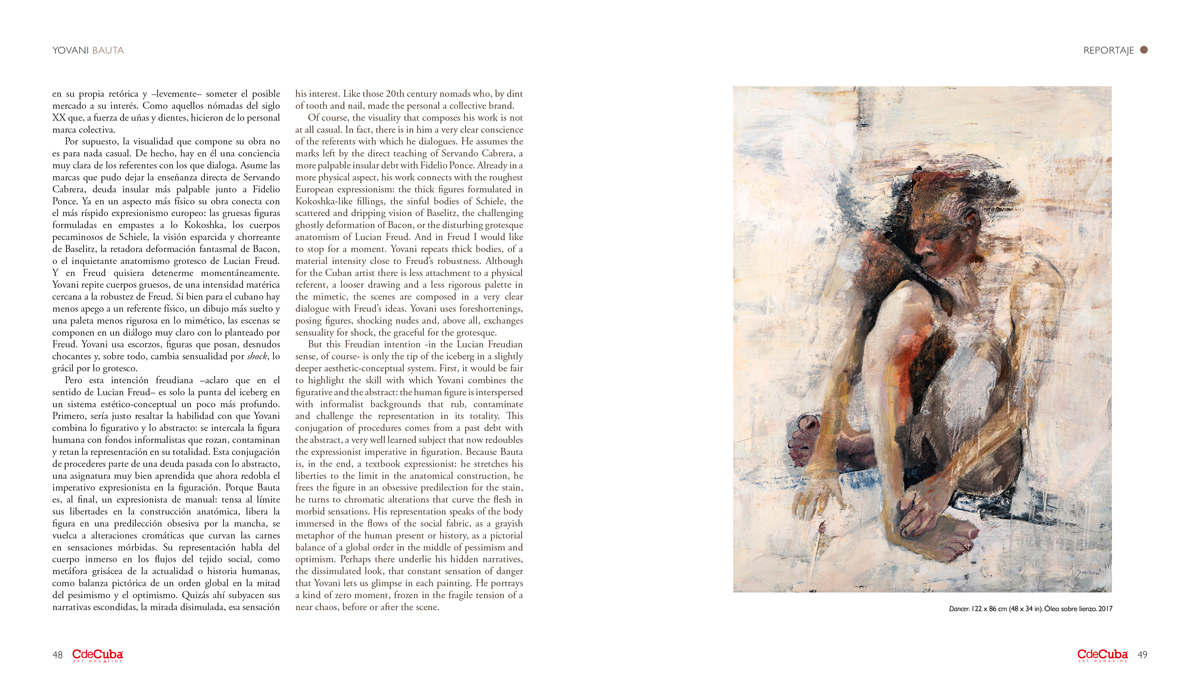

Of course, the visuality that composes his work is not at all casual. In fact, there is in him a very clear conscience of the referents with which he dialogues. He assumes the marks left by the direct teaching of Servando Cabrera, a more palpable insular debt with Fidelio Ponce. Already in a more physical aspect, his work connects with the roughest European expressionism: the thick figures formulated in Kokoshka-like fillings, the sinful bodies of Schiele, the scattered and dripping vision of Baselitz, the challenging ghostly deformation of Bacon, or the disturbing grotesque anatomism of Lucian Freud. And in Freud I would like to stop for a moment. Yovani repeats thick bodies, of a material intensity close to Freud’s robustness. Although for the Cuban artist there is less attachment to a physical referent, a looser drawing and a less rigorous palette in the mimetic, the scenes are composed in a very clear dialogue with Freud’s ideas. Yovani uses foreshortenings, posing figures, shocking nudes and, above all, exchanges sensuality for shock, the graceful for the grotesque.

But this Freudian intention -in the Lucian Freudian sense, of course- is only the tip of the iceberg in a slightly deeper aesthetic-conceptual system. First, it would be fair to highlight the skill with which Yovani combines the figurative and the abstract: the human figure is interspersed with informalist backgrounds that rub, contaminate and challenge the representation in its totality. This conjugation of procedures comes from a past debt with the abstract, a very well learned subject that now redoubles the expressionist imperative in figuration. Because Bauta is, in the end, a textbook expressionist: he stretches his liberties to the limit in the anatomical construction, he frees the figure in an obsessive predilection for the stain, he turns to chromatic alterations that curve the flesh in morbid sensations. His representation speaks of the body immersed in the flows of the social fabric, as a grayish metaphor of the human present or history, as a pictorial balance of a global order in the middle of pessimism and optimism. Perhaps there underlie his hidden narratives, the dissimulated look, that constant sensation of danger that Yovani lets us glimpse in each painting. He portrays a kind of zero moment, frozen in the fragile tension of a near chaos, before or after the scene.

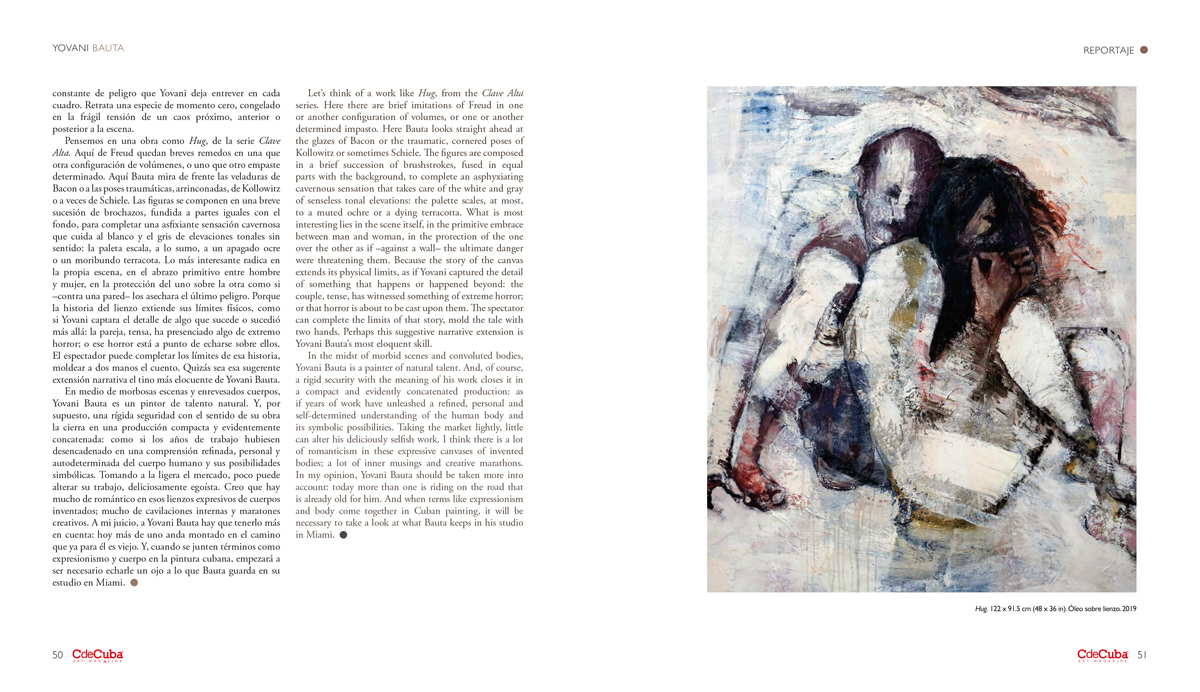

Let’s think of a work like Hug, from the Clave Alta series. Here there are brief imitations of Freud in one or another configuration of volumes, or one or another determined impasto. Here Bauta looks straight ahead at the glazes of Bacon or the traumatic, cornered poses of Kollowitz or sometimes Schiele. The figures are composed in a brief succession of brushstrokes, fused in equal parts with the background, to complete an asphyxiating cavernous sensation that takes care of the white and gray of senseless tonal elevations: the palette scales, at most, to a muted ochre or a dying terracotta. What is most interesting lies in the scene itself, in the primitive embrace between man and woman, in the protection of the one over the other as if –against a wall– the ultimate danger were threatening them. Because the story of the canvas extends its physical limits, as if Yovani captured the detail of something that happens or happened beyond: the couple, tense, has witnessed something of extreme horror; or that horror is about to be cast upon them. The spectator can complete the limits of that story, mold the tale with two hands. Perhaps this suggestive narrative extension is Yovani Bauta’s most eloquent skill.

In the midst of morbid scenes and convoluted bodies, Yovani Bauta is a painter of natural talent. And, of course, a rigid security with the meaning of his work closes it in a compact and evidently concatenated production: as if years of work have unleashed a refined, personal and self-determined understanding of the human body and its symbolic possibilities. Taking the market lightly, little can alter his deliciously selfish work. I think there is a lot of romanticism in these expressive canvases of invented bodies; a lot of inner musings and creative marathons. In my opinion, Yovani Bauta should be taken more into account: today more than one is riding on the road that is already old for him. And when terms like expressionism and body come together in Cuban painting, it will be necessary to take a look at what Bauta keeps in his studio in Miami.