The Man, The Patriot and The Traitor

By Héctor Antón

In the affirmative discourse of the Cuban Revolution, it plays a leading role to evoke the overlooked or forgotten passages of the patriotic deed. Through the press, literature, cinema or television, the cultural policy is concerned that young people avoid the epic that sustains a rhetoric in love with itself, in a kind of anthropophagic process that fights to recycle itself, eager for longevity. At the same time, those interested in rescuing history hidden in anecdotal journeys emerge from the margins. That which the hegemonic rewriting conceals , labeling it as a pernicious revisionism.

Huber Matos Benitez (Yara, Cuba, 1918 – Miami, Florida, United States, 2014) was one of the bearded men who led the armed insurrection that overthrew Fulgencio Batista’s dictatorship in 1959. For the memory of the exile, he is the first guerrilla commander to separate himself from the socialist process, which is why he was sentenced to twenty years in prison, to end his days in the banishment of powerlessness. Exile is an euphemism for a radio aura in his case.

For the insular amnesia, Huber Matos is a counterrevolutionary sold to the enemy, dissatisfied with seeing his yearning for unipersonal protagonism frustrated; another representative of the radical positions of the Cuban American mafia. Huber Matos would be the author of a somber and inflated testimony, a powdery reconstruction in the archives of resentment, under the motif of a novel.

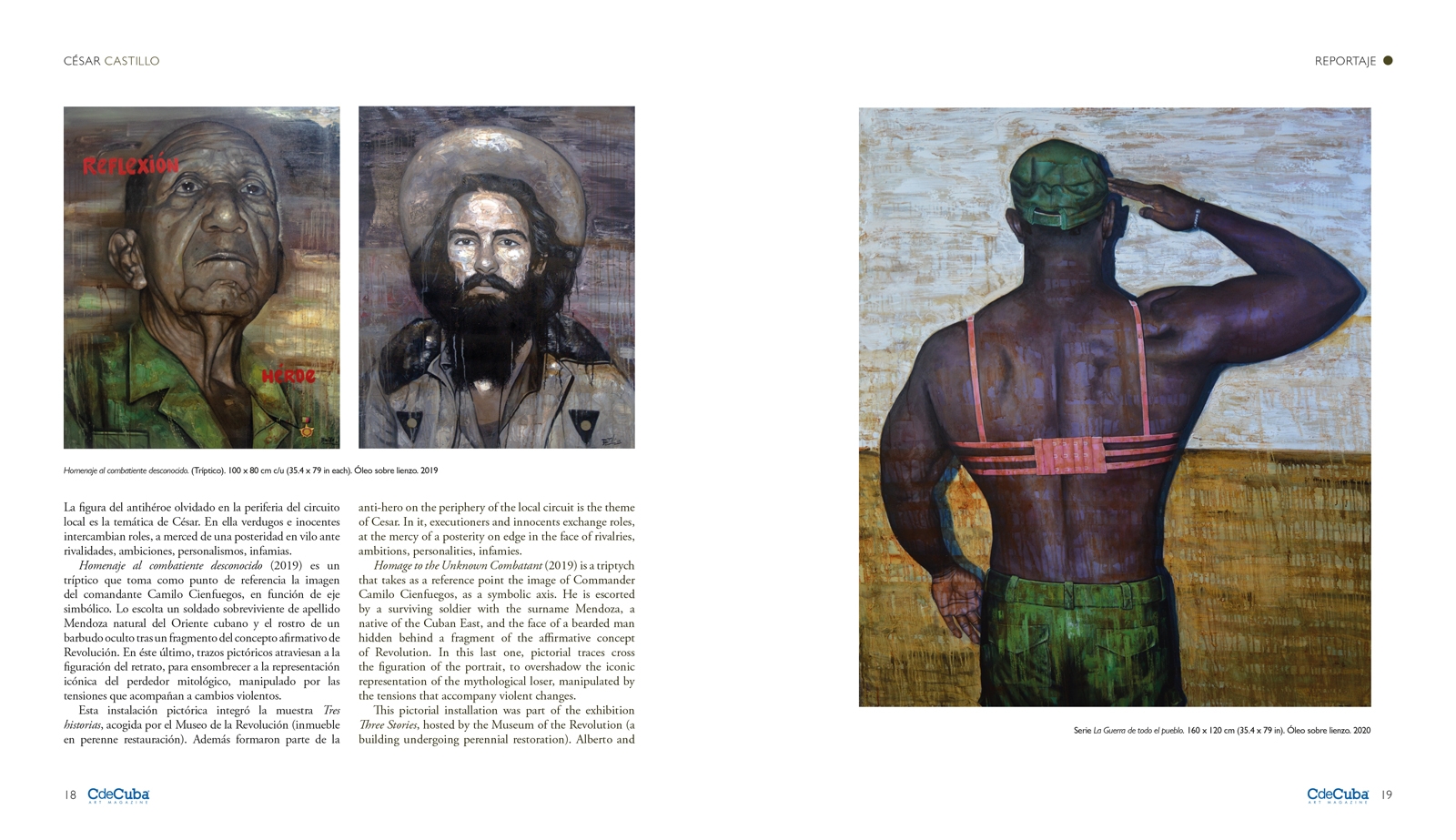

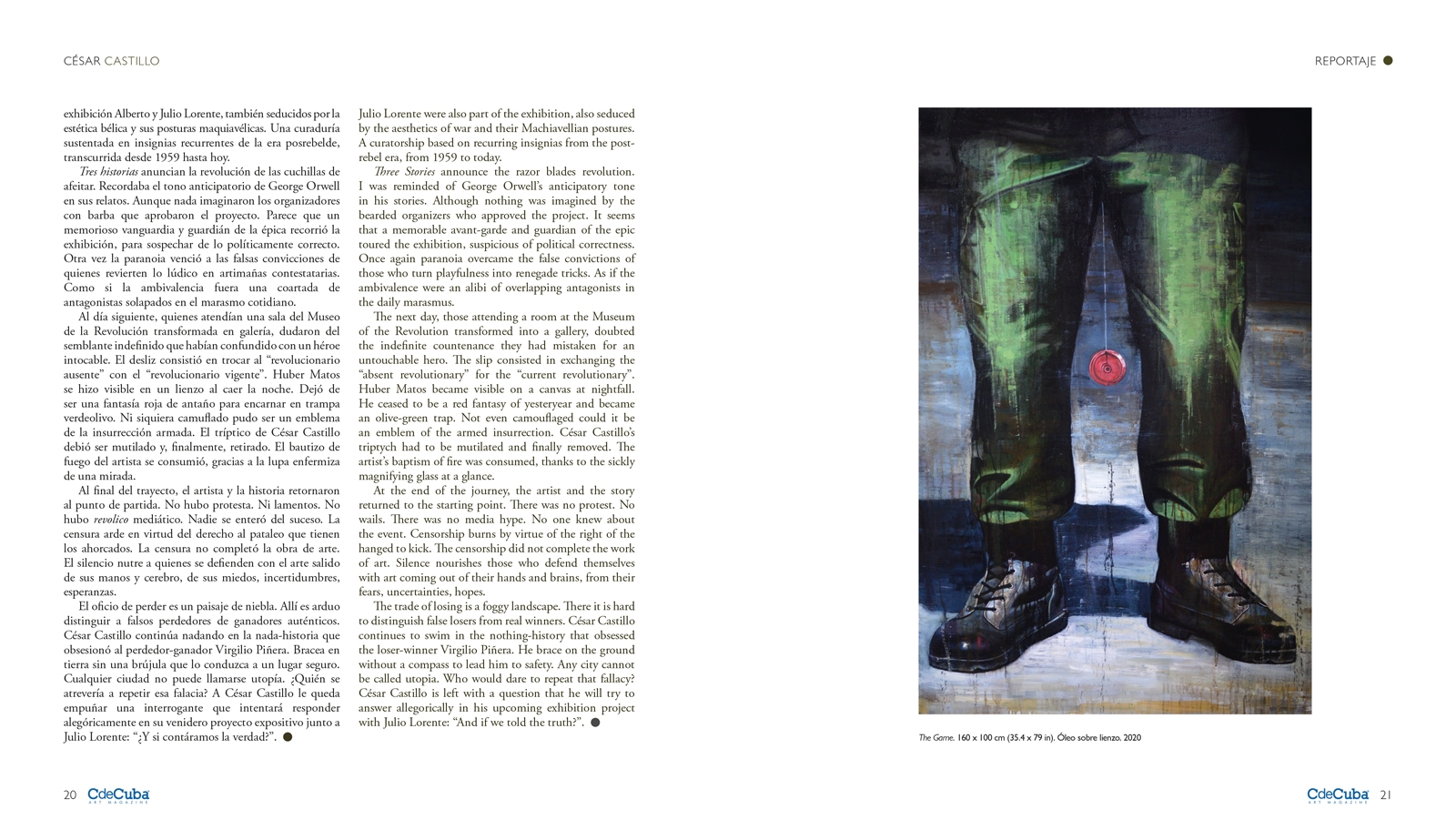

Cesar Castillo (Granma, Cuba, 1987) delves into the folds of a political art in his own way. He rules out media hype as an advertising strategy. He does not aspire to become a tropical remix of the Chinese artist Ai Weiwei, cynical enough to live in danger, to elude the power and be praised by the masses. The figure of the forgotten

anti-hero on the periphery of the local circuit is the theme of Cesar. In it, executioners and innocents exchange roles, at the mercy of a posterity on edge in the face of rivalries, ambitions, personalities, infamies.

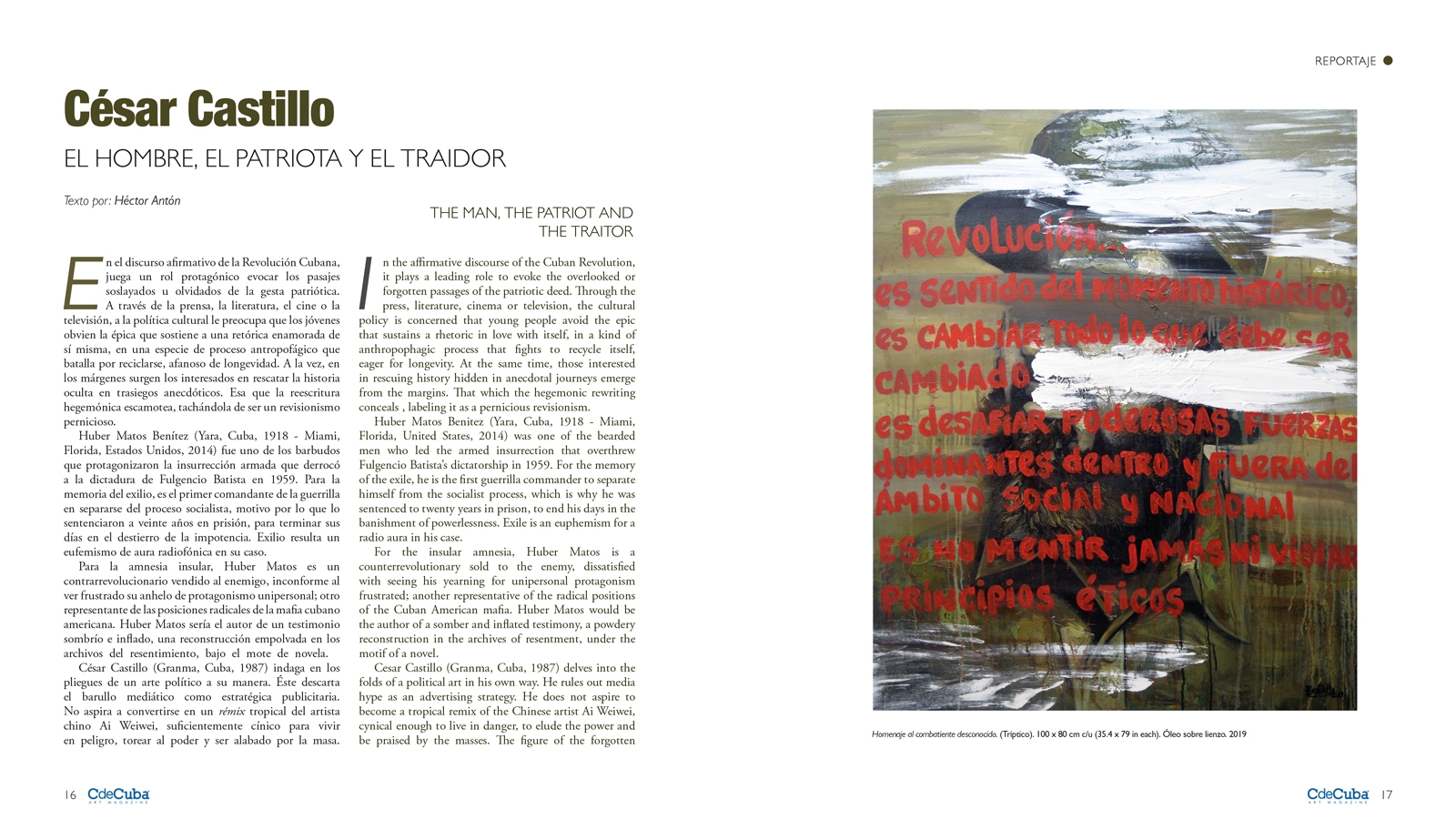

Homage to the Unknown Combatant (2019) is a triptych that takes as a reference point the image of Commander Camilo Cienfuegos, as a symbolic axis. He is escorted by a surviving soldier with the surname Mendoza, a native of the Cuban East, and the face of a bearded man hidden behind a fragment of the affirmative concept of Revolution. In this last one, pictorial traces cross the figuration of the portrait, to overshadow the iconic representation of the mythological loser, manipulated by the tensions that accompany violent changes.

This pictorial installation was part of the exhibition Three Stories, hosted by the Museum of the Revolution (a building undergoing perennial restoration). Alberto and

Julio Lorente were also part of the exhibition, also seduced by the aesthetics of war and their Machiavellian postures. A curatorship based on recurring insignias from the post-rebel era, from 1959 to today.

Three Stories announce the razor blades revolution. I was reminded of George Orwell’s anticipatory tone in his stories. Although nothing was imagined by the bearded organizers who approved the project. It seems that a memorable avant-garde and guardian of the epic toured the exhibition, suspicious of political correctness. Once again paranoia overcame the false convictions of those who turn playfulness into renegade tricks. As if the ambivalence were an alibi of overlapping antagonists in the daily marasmus.

The next day, those attending a room at the Museum of the Revolution transformed into a gallery, doubted the indefinite countenance they had mistaken for an untouchable hero. The slip consisted in exchanging the “absent revolutionary” for the “current revolutionary”. Huber Matos became visible on a canvas at nightfall. He ceased to be a red fantasy of yesteryear and became an olive-green trap. Not even camouflaged could it be an emblem of the armed insurrection. César Castillo’s triptych had to be mutilated and finally removed. The artist’s baptism of fire was consumed, thanks to the sickly magnifying glass at a glance.

At the end of the journey, the artist and the story returned to the starting point. There was no protest. No wails. There was no media hype. No one knew about the event. Censorship burns by virtue of the right of the hanged to kick. The censorship did not complete the work of art. Silence nourishes those who defend themselves with art coming out of their hands and brains, from their fears, uncertainties, hopes.

The trade of losing is a foggy landscape. There it is hard to distinguish false losers from real winners. César Castillo continues to swim in the nothing-history that obsessed the loser-winner Virgilio Piñera. He brace on the ground without a compass to lead him to safety. Any city cannot be called utopia. Who would dare to repeat that fallacy? César Castillo is left with a question that he will try to answer allegorically in his upcoming exhibition project with Julio Lorente: “And if we told the truth?”.