Synthetic and Symbolic Neo-Cubism

By Mª del Socorro MoraC

To approach the life and work of Felipe Alarcón Echenique is to reflect on the vicissitudes of destiny, the ups and downs of genes, the mutual cultural influences between America and Europe; and, of course, it is to speak of the biological and pluricultural crossbreeding that continues and will continue to occur in the world. Because the exchange of genes and memes is key to our survival. This mobility that our species, driven by chance and necessity, creativity and curiosity, has been our flag since the beginning. A flag is a symbol that means something to someone. Dissatisfaction is a sign of human beings in general and of restless minds in particular. This is the case of Felipe Alarcón, his native Cuba was too small for his aspirations and he had to fly to build with his restless hands and his hyperactive brain another destiny, another path, another place to dream, and where to continue growing both personally and plastically.

Scientists wonder what happens in our brains when we make certain choices. Are we in the hands of fate? Are we puppets of chance? Are we free to choose? Are we really conscious of our choices? Are we willing to assume the consequences of our actions? In both science and art we conduct experiments. But let us remember that life itself is an experiment. The truth is that our brain is often a battlefield. According to Schiller, man can be in contradiction with himself either as a savage or as a barbarian. And he writes something very neurobiological and ecological: “The educated man makes nature his friend and honors its freedom by simply restraining its whims”. Felipe Alarcón Echenique is an artist worth contemplating, from a neuroesthetic point of view. It would be interesting to observe Felipe’s restless brain in action.

In order to understand the work of our artist we will go back to the first decade of the last century and try to answer some questions about cubism that surely many have asked and continue to ask.

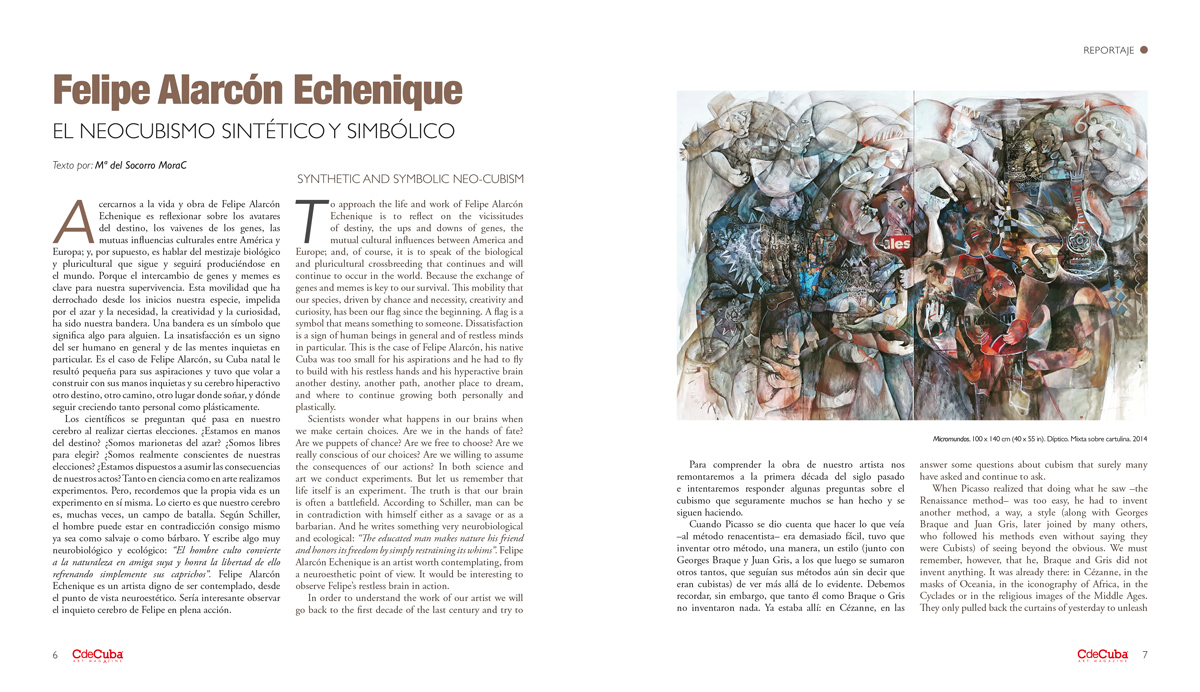

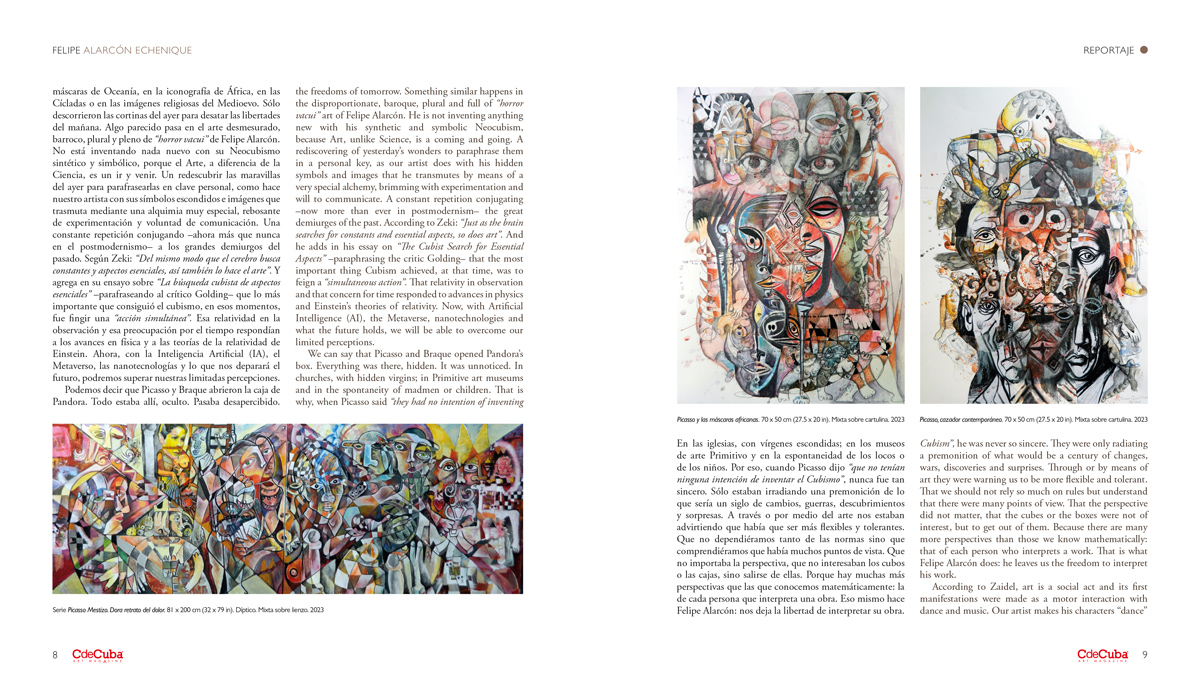

When Picasso realized that doing what he saw –the Renaissance method- was too easy, he had to invent another method, a way, a style (along with Georges Braque and Juan Gris, later joined by many others, who followed his methods even without saying they were Cubists) of seeing beyond the obvious. We must remember, however, that he, Braque and Gris did not invent anything. It was already there: in Cézanne, in the masks of Oceania, in the iconography of Africa, in the Cyclades or in the religious images of the Middle Ages. They only pulled back the curtains of yesterday to unleash the freedoms of tomorrow. Something similar happens in the disproportionate, baroque, plural and full of “horror vacui” art of Felipe Alarcón. He is not inventing anything new with his synthetic and symbolic Neocubism, because Art, unlike Science, is a coming and going. A rediscovering of yesterday’s wonders to paraphrase them in a personal key, as our artist does with his hidden symbols and images that he transmutes by means of a very special alchemy, brimming with experimentation and will to communicate. A constant repetition conjugating –now more than ever in postmodernism– the great demiurges of the past. According to Zeki: “Just as the brain searches for constants and essential aspects, so does art”. And he adds in his essay on “The Cubist Search for Essential Aspects” –paraphrasing the critic Golding- that the most important thing Cubism achieved, at that time, was to feign a “simultaneous action”. That relativity in observation and that concern for time responded to advances in physics and Einstein’s theories of relativity. Now, with Artificial Intelligence (AI), the Metaverse, nanotechnologies and what the future holds, we will be able to overcome our limited perceptions.

We can say that Picasso and Braque opened Pandora’s box. Everything was there, hidden. It was unnoticed. In churches, with hidden virgins; in Primitive art museums and in the spontaneity of madmen or children. That is why, when Picasso said “they had no intention of inventing Cubism”, he was never so sincere. They were only radiating a premonition of what would be a century of changes, wars, discoveries and surprises. Through or by means of art they were warning us to be more flexible and tolerant. That we should not rely so much on rules but understand that there were many points of view. That the perspective did not matter, that the cubes or the boxes were not of interest, but to get out of them. Because there are many more perspectives than those we know mathematically: that of each person who interprets a work. That is what Felipe Alarcón does: he leaves us the freedom to interpret his work.

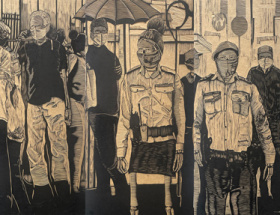

According to Zaidel, art is a social act and its first manifestations were made as a motor interaction with dance and music. Our artist makes his characters “dance” with a rhythm that is sometimes slow, sometimes frenetic; but always with a clear intention of communicating not only aesthetic but also social, literary or cultural concerns. “His works are a chronicle of everyday events”.

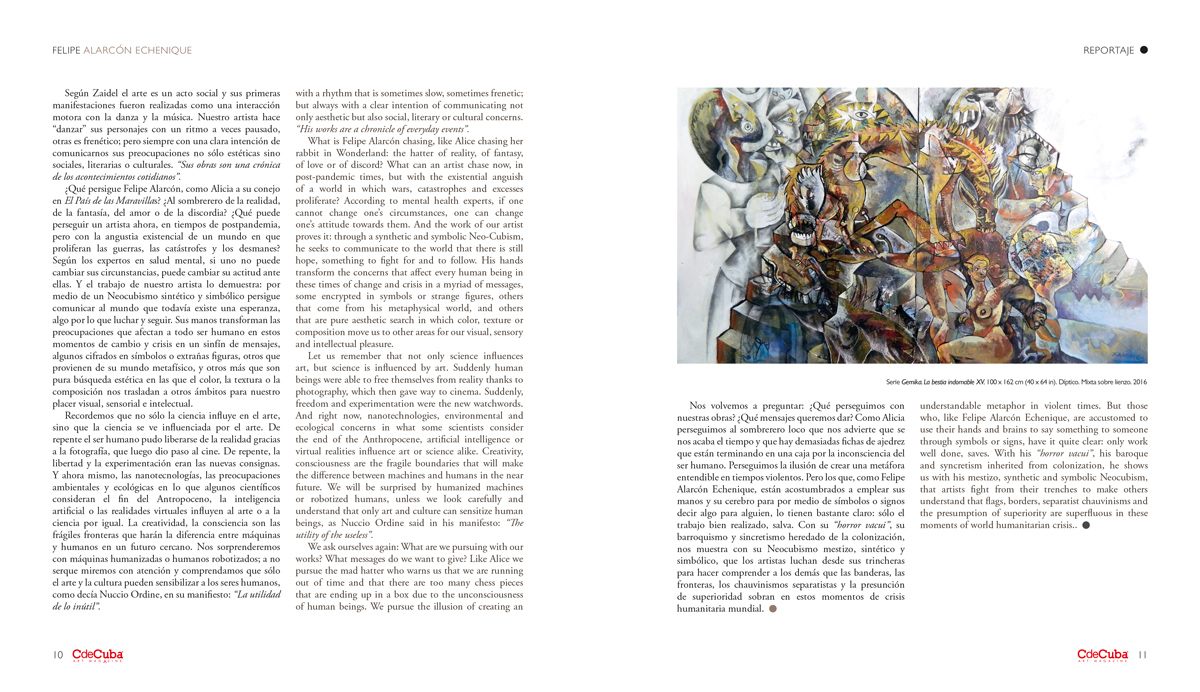

What is Felipe Alarcón chasing, like Alice chasing her rabbit in Wonderland: the hatter of reality, of fantasy, of love or of discord? What can an artist chase now, in post-pandemic times, but with the existential anguish of a world in which wars, catastrophes and excesses proliferate? According to mental health experts, if one cannot change one’s circumstances, one can change one’s attitude towards them. And the work of our artist proves it: through a synthetic and symbolic Neo-Cubism, he seeks to communicate to the world that there is still hope, something to fight for and to follow. His hands transform the concerns that affect every human being in these times of change and crisis in a myriad of messages, some encrypted in symbols or strange figures, others that come from his metaphysical world, and others that are pure aesthetic search in which color, texture or composition move us to other areas for our visual, sensory and intellectual pleasure.

Let us remember that not only science influences art, but science is influenced by art. Suddenly human beings were able to free themselves from reality thanks to photography, which then gave way to cinema. Suddenly, freedom and experimentation were the new watchwords. And right now, nanotechnologies, environmental and ecological concerns in what some scientists consider the end of the Anthropocene, artificial intelligence or virtual realities influence art or science alike. Creativity, consciousness are the fragile boundaries that will make the difference between machines and humans in the near future. We will be surprised by humanized machines or robotized humans, unless we look carefully and understand that only art and culture can sensitize human beings, as Nuccio Ordine said in his manifesto: “The utility of the useless”.

We ask ourselves again: What are we pursuing with our works? What messages do we want to give? Like Alice we pursue the mad hatter who warns us that we are running out of time and that there are too many chess pieces that are ending up in a box due to the unconsciousness of human beings. We pursue the illusion of creating an understandable metaphor in violent times. But those who, like Felipe Alarcón Echenique, are accustomed to use their hands and brains to say something to someone through symbols or signs, have it quite clear: only work well done, saves. With his “horror vacui”, his baroque and syncretism inherited from colonization, he shows us with his mestizo, synthetic and symbolic Neocubism, that artists fight from their trenches to make others understand that flags, borders, separatist chauvinisms and the presumption of superiority are superfluous in these moments of world humanitarian crisis.