Optical Ideology

By Héctor Antón

Cuban abstract painting is homogeneous, self-complacent and frying. It consists of an “arbitrary” and “scattered” cast of craftsmen who love-hate one another because they do not mark each other’s territory. There are exceptions, of course, and at times it is comforting to delight in the ruinous textures of someone like Rigoberto Mena.

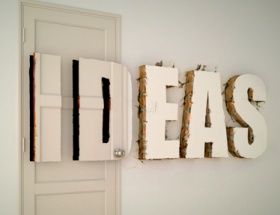

Rene Rodriguez (Santa Clara, 1966) is not just another abstract painter nor is he a minimalist, although he likes to combine close-distant variables in his formal-conceptual maneuvers. He is rather an outsider of the Academy and the street by proving the suspicion that “Art is not taught”.

Faithful to the legacy of Barnett Newman, Ad Reinhardt, Brice Marden or Ellsworth Kelly, Rene Rodriguez seeks to rescue the content, the last almost non-existent redoubt in abstract-minimalist proposals, clinging to the dogma of “non-reading” in the key of textual subjectivity.

One of our forerunners of this line, reluctant to the virtuosity of the brushstroke, has been Flavio Garciandia, professor without a chair or master without a National Prize in Visual Arts because he lives in Mexico City; a man of art determined to frighten away the nickname “stupid as a painter” coined by Marcel Duchamp. Flavio spends more time thinking about a painting than painting a canvas. A habit that separates him from the artisans who insist and persist in trying to differentiate sky, sea and land.

The reference that illuminated Rene’s strategic course was a Cuban artist who absorbed Andy Warhol’s and Roy Lichtenstein’s pop to remain on his Island shaken by the triumphal irruption of the bearded ones. What the young Raul Martinez did not foresee ended in a paralyzing collective trauma: the ideo-aesthetic discourse of the Cuban Revolution undertook a radicalization (socialist?) process, to the point of demonizing everything that came from the “revolted and brutal north”.

The ghost of ideological divergence toured the archipelago, and titles inherited from the Russian productivism emerged: Estudio, trabajo, fusil (1973), by Nelida Lopez; Macheteros (1975) and Imágenes de Angola victoriosa (1976), by Roberto Fabelo. The set was ready to shoot scenes of that “generation of guaranteed hope”. The pamphlet and its utopian complex would be the art of a heroic era.

Raul Martinez transformed the iron curtain justified by the Cold War into the resource of method. This was achieved by deploying a “revolutionary pop” where the almost expressionist patriotic portraits granted a charismatic aesthetic irony to the “passionate” serial paintings.

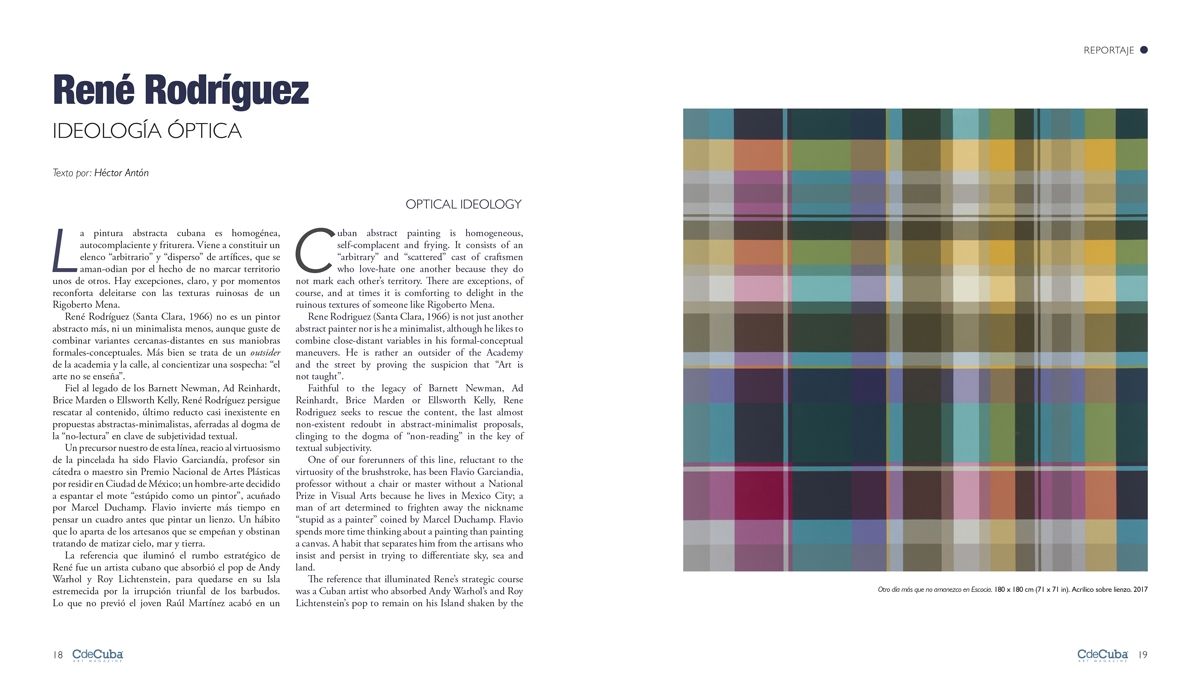

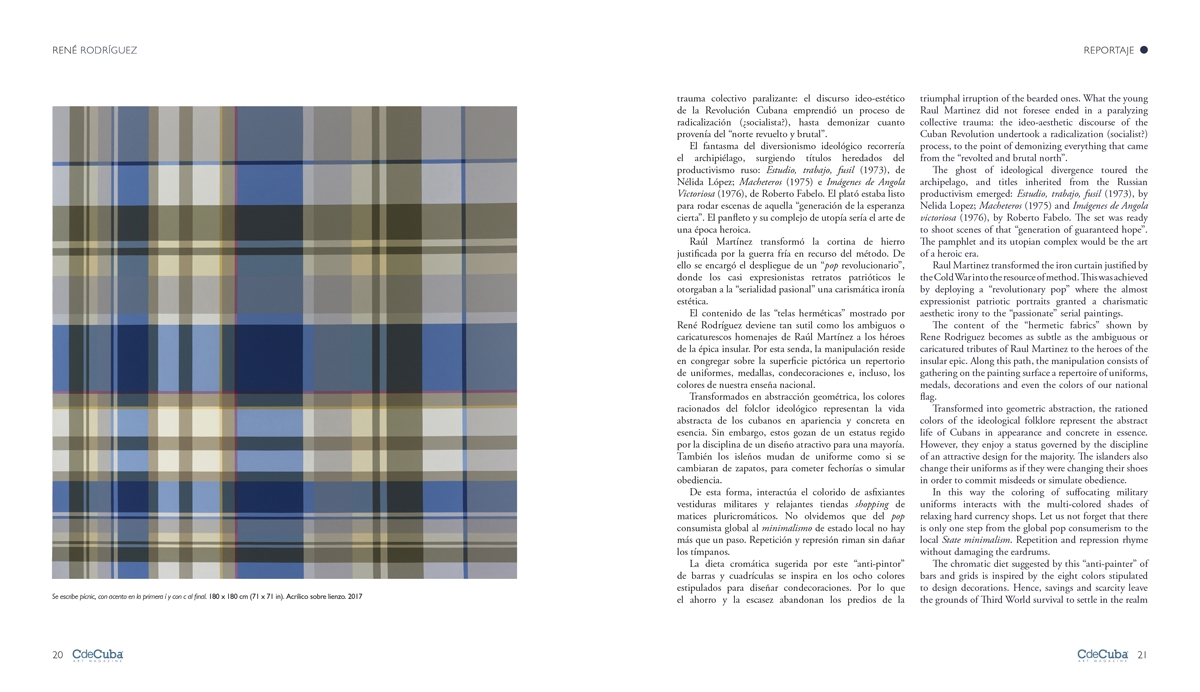

The content of the “hermetic fabrics” shown by Rene Rodriguez becomes as subtle as the ambiguous or caricatured tributes of Raul Martinez to the heroes of the insular epic. Along this path, the manipulation consists of gathering on the painting surface a repertoire of uniforms, medals, decorations and even the colors of our national flag.

Transformed into geometric abstraction, the rationed colors of the ideological folklore represent the abstract life of Cubans in appearance and concrete in essence. However, they enjoy a status governed by the discipline of an attractive design for the majority. The islanders also change their uniforms as if they were changing their shoes in order to commit misdeeds or simulate obedience.

In this way the coloring of suffocating military uniforms interacts with the multi-colored shades of relaxing hard currency shops. Let us not forget that there is only one step from the global pop consumerism to the local State minimalism. Repetition and repression rhyme without damaging the eardrums.

The chromatic diet suggested by this “anti-painter” of bars and grids is inspired by the eight colors stipulated to design decorations. Hence, savings and scarcity leave the grounds of Third World survival to settle in the realm of elitist modalities such as post-pictorial abstraction or perverse post-minimalism. As wishing to revert control into visual enjoyment.

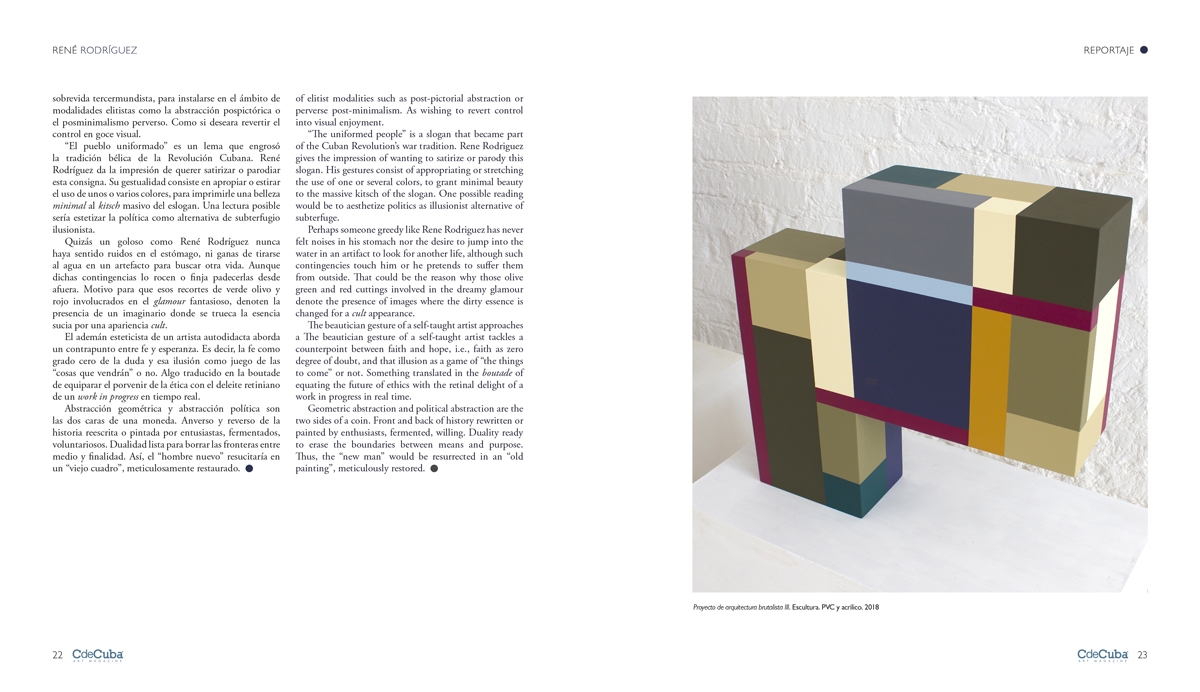

“The uniformed people” is a slogan that became part of the Cuban Revolution’s war tradition. Rene Rodriguez gives the impression of wanting to satirize or parody this slogan. His gestures consist of appropriating or stretching the use of one or several colors, to grant minimal beauty to the massive kitsch of the slogan. One possible reading would be to aesthetize politics as illusionist alternative of subterfuge.

Perhaps someone greedy like Rene Rodriguez has never felt noises in his stomach nor the desire to jump into the water in an artifact to look for another life, although such contingencies touch him or he pretends to suffer them from outside. That could be the reason why those olive green and red cuttings involved in the dreamy glamour denote the presence of images where the dirty essence is changed for a cult appearance.

The beautician gesture of a self-taught artist tackles a counterpoint between faith and hope, i.e., faith as zero degree of doubt, and that illusion as a game of “the things to come” or not. Something translated in the boutade of equating the future of ethics with the retinal delight of a work in progress in real time.

Geometric abstraction and political abstraction are the two sides of a coin. Front and back of history rewritten or painted by enthusiasts, fermented, willing. Duality ready to erase the boundaries between means and purpose. Thus, the “new man” would be resurrected in an “old painting”, meticulously restored.