Fedón’s Story

By Isdanny Morales Sosa

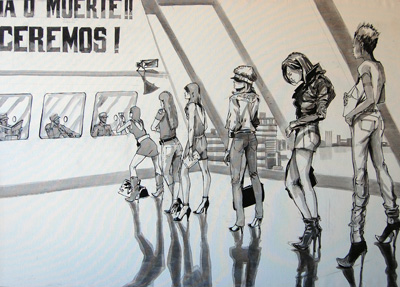

War has not ceased during two millenniums. Apollo has riddled Dionysius all this time. The battle field is where each man is. Socrates is to blame for war; Plato is the accomplice. The motif is always power. The Apollonians consider themselves bulwarks of alleged Morals, Truth, and Beauty; the Dionysians are bulwarks of Ecstasy, Licentiousness, and Passions. War will continue as long as there is no dialogue between the two armies. The work of artist Miriannys Montes de Oca provides a large repertory of images of the present state of this war. It is a conflict that today develops along more subtle paths than the crusader’s bloody sword or the inquisitor’s stake. Apollonians and Dionysians have adopted more sophisticated methods. Their ever more effective messages spread an alienating avalanche upon mankind, which only succeeds in experiencing its consequences as sustained anguish. Today, a silent war is taking place.

Miriannys’ eyes are fixed upon humans. She is motivated, not by the great chronicles of heroes, but by the intimate histories. Each one of her pieces is part of a large narrative where she reinterprets in art the permanent dilemma of each individual: the fracture between the social being and the expectations of the Ego. The story that moved her to create the series Los soportables pesos del ser (The Bearable Burden Of The Being) (her graduation thesis at the University of the Arts), was her father’s, typical dreamer that constantly is descended of the clouds. Childhood, youth and adulthood are included by Miriannys in metaphorical form in a kind of cinematographic painting that ends in a symbolical suicide representing the death of utopia. Next to the father as central iconic element, other characters represent the persons who accompany him in life, who symbolize the social network.

The visualization of the others in the series Escenas (Scenes) based on the artist’s photographs of theatrical and contemporary dance presentations was essentially phantasmagorical. Their ghastly bodies reeked of death, bile and ruin. Others leaped on the subject like a devouring and frightening machine, and were visually connected with the codes of German expressionist films. This may be explained if we trace contact lines between Miriannys’ aesthetic thesis and those of the German movement. The expressionist movies, just like the work of this artist, denounced out loud the consequences of a “perverse modernity”, whose consequences are a deep existential anguish, the restrained hegemonic exercise of Reason and the individual’s automation in hysterical race to transcend.

The others in Los soportables pesos del ser (The Bearable Burden Of The Being) also have an expressionist dimension, but not a negative one, as consequence of the very process of creation. Miriannys summons to a theater to a group of “actors”, who are not more than her relatives and friends. She dressed them, makes up and directs. She creates the prop and works the lights. She becomes scriptwriter, make up person, scenographer, technician of lights and director at the same time. The “actors” are photographed and used as motif to construct the paintings. The others, the ghastly and inquisitive mass presented in other series has more naturalist and friendly tints here. She knows that, like her father, they are victims of an Apollonian state of affairs, which explains why these pieces are less ghastly than the others. Like the ones that appear in La marcha de las antorchas (The March with Torches) and Amanda, la niña vecina del frente (Amanda, the Neighbor Girl from Across the Street), they have ceased to be that threatening avalanche on the subject and have also become wounded.

The theatrical nature itself operates on a metaphorical key to allude to a life, the western one, which historically develops as a great staging. The Apollonian dimension intrinsic to western metaphysics has condemned those subjects to life imprisonment in themselves because the human being must constantly play a role, simulate ideologies and feelings in order to fit into the requirements demanded by the social network. This, on one side, produces frustration, a fracture between the Apollonian/Dionysian impulses, and on the other side is an instinct of survival. The image of her entire work is marked by a dual condition: on one side, the gloomy, dramatic and theatrical nature of profoundly disturbing and enigmatic characters; on the other side, “beauty”, the arabesque, flowers and the tender detail. But beware: what might seem beautiful in her work is just a simulacrum that alludes to all the artifices that humans avail themselves of to disguise their scars, their poverty and the frustration of being riddled over and over again by Apollo. Dionysius loses again. Socrates is always to blame. The human being has to endure his condition.