José Capaz: Divergent Paths

By Carlos Jaime Jiménez

Although I am convinced that nothing changes,

it is important for me to act as if I ignored it.

Leonard Cohen

In the foreword to her first book of essays, Susan Sontag mentions the effect exerted on her by the feverish creative explosion that shook the artistic and cultural scene of the west during the decade of 1960. The overload of stimuli and interesting options paradoxically became almost an impediment for those who regarded the field of art not as a plot but as a fast-growing root. Consequently, she decided to assume the risk of simultaneously going in all directions after realizing that eventually that was the road followed by several of the artists that most interested and influenced her.

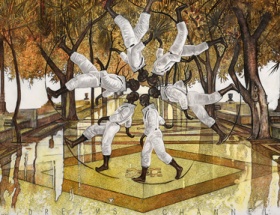

Half a century later and in a different context, the work of José Capaz evidences a similar discursive will, based on an omnivorous appetite for the contemporary visual culture and the western artistic tradition. The artist makes both universes coincide, opening a range of expressive possibilities that enable him to dialogue with multiple social and aesthetic issues. Thus, when his work brings together the trace of a Rembrandt piece and an over-dimensioned emoji in all its obscene superficiality, the question emerges of how the interaction of new virtual media complicates the reception of classic art, confronting at the same time the new paradigms that rule the visual imagery of the present society. The ultimate purpose is not to blur the borders between low and high brow (which would only follow a decade-long profusely treaded path), but rather investigate the way in which the sensibility of the contemporary individual has changed with the saturation of images and information to which he is constantly exposed.

In this context where the reception of art is less and less ruled by an aesthetic norm, José Capaz in his series Ictericia (Jaundice) continues his search on the persistence of the “aura” of classic works that is now part of the dynamics of rapid image consumption that characterizes the present society. His main purpose is to escape the abyss that exists between validating through the form and the imperative of the concept. The subversion of the classic reference masks an apology of the great masters’ painting craft, ever more difficult to appreciate, particularly if the reception takes place through the screen of an electronic device.

The artist is capable of following several paths at the same time, as the result of an extremely far-reaching creative ambition concerning themes and style. His art maintains a coherence that is only understood when realizing to what extent his work is indebted with fragments and with representation models that mix and superimpose around a repeated motif. Such is the case of the pieces that make up the series Una pintura de género (A Genre Painting) through which the creator avails himself of the representation of tongues understood as concrete variations of a symbol of multiple echoes and meanings. In some cases the tongues invade the entire canvas; in others they contribute to dramatize classic scenes such as seascapes, or convulse reproductions of battles resulting from the imagery of Romanticism. They always introduce a sort of estrangement, and their presence, expressed in marked gestural strokes and thick pasting, has been injected with a disturbing metonymic value, as if its collateral meanings would suffice to describe the archetypical human being.

The dialogue between José Capaz’s work and the western art canon and its mutations slanting the visual culture of contemporariness does not merely respond to the urge of reformulating old questionings or solving current problems related with the validation of art. Several of his most recent pieces such as Paranoia or Pharmacy Blonde evidence a marked expressionist character and a dark atmosphere loaded with psychic impulses. Nevertheless, if we ask the artist he will probably tell us that the impulse (in his case the term seems more adequate than “inspiration”) to create them emerged from sources as scarcely predictable as the observation of a western or the contemplation of an 18th century portrait. The filter of his subjectivity takes care of the rest, meaning almost everything. This will to transform is not exactly the result of what Harold Bloom called “anguish of the influences” referring to writing, which is perfectly applicable to the artistic context. If José Capaz, having succeeded in externalizing his unconsciousness, were to meet his symbolical Padre, he would not for one moment consider beheading him. He would probably hold a cheerful conversation with him and hardly allow him to speak, commenting on the many projects he has in mind. Some he would even start during the conversation.